Tibet (1912–1951)

Tibet (Tibetan: བོད་, Wylie: Bod) was a de facto independent state in East Asia that lasted from the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912 until its annexation by the People's Republic of China in 1951.

[10][11] In 1912 the provisional government of the Republic of China (ROC) succeeded the Qing and received an imperial edict inheriting the claims over all of its territories.

The 13th Dalai Lama declared that Tibet's relationship with China ended with the fall of the Qing dynasty and proclaimed independence, although this was not formally recognized by other countries.

[17] After the 13th Dalai Lama's death in 1933, a condolence mission sent to Lhasa by the Kuomintang-ruled Nationalist government to start negotiations about Tibet's status was allowed to open an office and remain there, although no agreement was reached.

[22] Following the establishment of the new Republic, China's provisional President, Yuan Shikai, sent a telegram to the 13th Dalai Lama, restoring his earlier titles.

[25][26] In January 1913, Agvan Dorzhiev and three other Tibetan representatives[27] signed a treaty between Tibet and Mongolia in Urga, proclaiming mutual recognition and their independence from China.

The British diplomat Charles Bell wrote that the 13th Dalai Lama told him that he had not authorized Agvan Dorzhiev to conclude any treaties on behalf of Tibet.

The British suggested dividing Tibetan-inhabited areas into an Outer and an Inner Tibet (on the model of an earlier agreement between China and Russia over Mongolia).

In Inner Tibet, consisting of eastern Kham and Amdo, China would have rights of administration and Lhasa would retain control of religious institutions.

[39] According to Alastair Lamb, by refusing to sign the Simla documents, the Chinese Government had escaped giving any recognition to the McMahon Line.

[26] Direct communications resumed after the 13th Dalai Lama's death in December 1933,[26] when China sent a "condolence mission" to Lhasa headed by General Huang Musong.

[44] Since 1912, Tibet had been de facto independent of Chinese control, but on other occasions it had indicated willingness to accept nominal subordinate status as a part of China, provided that Tibetan internal systems were left untouched, and provided China relinquished control over a number of important ethnic Tibetan areas in Kham and Amdo.

For example, the Associated Press on Feb 22, 1940 writes: Lhasa, Tibet (Thursday) - (By Radio to Hong Kong) - [..] The Chinese government had worked for months to put the succession of Ling-ergh La-mu-tan-chu beyond the fortunes of the goldern urn from which the 14th Dalai Lama would normally be picked.

[53]Regarding the ceremony, according to Associated Press reports dated Feb 23, 1940: Direct word from Lhasa arrived only today, telling of the lengthy rites in which Chinese officials took part.

Feb 22 - The fourteenth Dalai Lama, who will share spiritual and temporal leadership of Tibet, was enthroned in a pompous elaborate ceremony today.

A departure from ordinary procedure was marked by display of a huge portrait of Dr. Sun Yat-sen and a Kuomintang flag in the golden main hall of the monastery.

[56]Britain, who had an interest in Tibet at the time and wished to undermine Chinese sovereignty over it, had a representative, Sir Basil Gould, who claims to have been present at the ceremony, and opposes the above diverse international sources that China presided over it.

Tibet established a Foreign Office in 1942, and in 1946 it sent congratulatory missions to China and India (related to the end of World War II).

Acting with a savagery which earned him the sobriquet of "The Butcher of Monks," he swept down on Batang, sacked the lamasery, pushed on to Chamdo, and in a series of victorious campaigns which brought his army to the gates of Lhasa, re-established order and reasserted Chinese domination over Tibet.

This project was not carried out until later, and then in modified form, for the Chinese Revolution of 1911 brought Chao's career to an end and he was shortly afterwards assassinated by his compatriots.

In 1914, Great Britain, China, and Tibet met at the conference table to try to restore peace, but this conclave broke up after failing to reach agreement on the fundamental question of the Sino-Tibetan frontier.

However, things gradually quieted down, and in 1927 the province of Sikang was brought into being, but it consisted of only twenty-seven subprefectures instead of the thirty-six visualized by the man who conceived the idea.

Since then, Sikang has been relatively peaceful, but this short synopsis of the province's history makes it easy to understand how precarious this state of affairs is bound to be.

To govern a territory of this kind, it is not enough to station, in isolated villages separated from each other by many days' journey, a few unimpressive officials and a handful of ragged soldiers.

Although on paper the wide territories to the north of the city form part of the Chinese provinces of Sikang and Tsinghai, the real frontier between China and Tibet runs through Kangting, or perhaps just outside it.

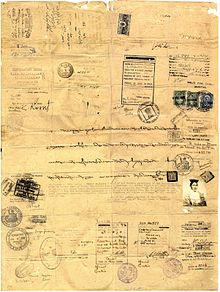

The empirical line which Chinese cartographers, more concerned with prestige than with accuracy, draw on their maps bears no relation to accuracy.In 1947–49, Lhasa sent a trade mission led by Finance Minister Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa to India, China, Hong Kong, the US, and the UK.

Traditional Tibetan society consisted of a feudal class structure, which was one of the reasons the Chinese Communist Party claims that it had to "liberate" Tibet and reform its government.

[94] Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan studies, Donald S. Lopez, stated that at the time: Traditional Tibet, like any complex society, had great inequalities, with power monopolized by an elite composed of a small aristocracy, the hierarchs of various sects .

[96] The 13th Dalai Lama had reformed the pre-existing serf system in the first decade of the 20th century, and by 1950, slavery itself had probably ceased to exist in central Tibet, though perhaps persisted in certain border areas.

Though rigid structurally, the system exhibited considerable flexibility at ground level, with peasants free of constraints from the lord of the manor once they had fulfilled their corvée obligations.