Tibeto-Burman languages

In the following century, Brian Houghton Hodgson collected a wealth of data on the non-literary languages of the Himalayas and northeast India, noting that many of these were related to Tibetan and Burmese.

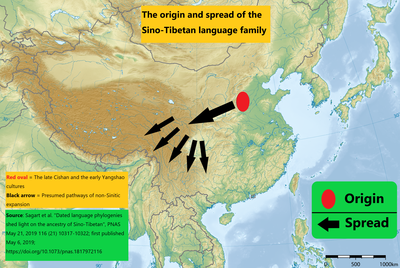

Julius Klaproth had noted in 1823 that Burmese, Tibetan and Chinese all shared common basic vocabulary, but that Thai, Mon and Vietnamese were quite different.

[11] Several authors, including Ernst Kuhn in 1883 and August Conrady in 1896, described an "Indo-Chinese" family consisting of two branches, Tibeto-Burman and Chinese-Siamese.

Jean Przyluski introduced the term sino-tibétain (Sino-Tibetan) as the title of his chapter on the group in Antoine Meillet and Marcel Cohen's Les Langues du Monde in 1924.

In spite of the popularity of this classification, first proposed by Kuhn and Conrady, and also promoted by Paul Benedict (1972) and later James Matisoff, Tibeto-Burman has not been demonstrated to be a valid subgroup in its own right.

[21] The Tibeto-Burman languages of south-west China have been heavily influenced by Chinese over a long period, leaving their affiliations difficult to determine.

[22] The hills of northwestern Sichuan are home to the small Qiangic and Rgyalrongic groups of languages, which preserve many archaic features.

The most easterly Tibeto-Burman language is Tujia, spoken in the Wuling Mountains on the borders of Hunan, Hubei, Guizhou and Chongqing.

[23] Over eight million people in the Tibetan Plateau and neighbouring areas in Baltistan, Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan speak one of several related Tibetic languages.

[24] Most of the languages of Bhutan are Bodish, but it also has three small isolates, 'Ole ("Black Mountain Monpa"), Lhokpu and Gongduk and a larger community of speakers of Tshangla.

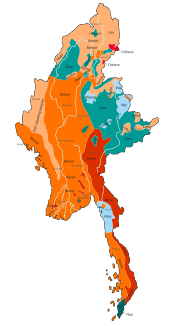

[27] The greatest variety of languages and subgroups is found in the highlands stretching from northern Myanmar to northeast India.

Northern Myanmar is home to the small Nungish group, as well as the Jingpho–Luish languages, including Jingpho with nearly a million speakers.

Shafer's tentative classification took an agnostic position and did not recognize Tibeto-Burman, but placed Chinese (Sinitic) on the same level as the other branches of a Sino-Tibetan family.

The Tibeto-Burman family is then divided into seven primary branches: James Matisoff proposes a modification of Benedict that demoted Karen but kept the divergent position of Sinitic.

Since Benedict (1972), many languages previously inadequately documented have received more attention with the publication of new grammars, dictionaries, and wordlists.

The internal structure of Tibeto-Burman is tentatively classified as follows by Matisoff (2015: xxxii, 1123–1127) in the final release of the Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus (STEDT).