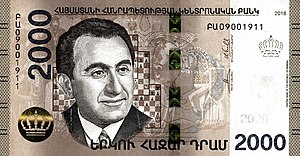

Tigran Petrosian

Ebralidze was a supporter of Nimzowitsch and Capablanca, and his scientific approach to chess discouraged wild tactics and dubious combinations.

[8] After training at the Palace of Pioneers for just one year, he defeated visiting Soviet grandmaster Salo Flohr at a simultaneous exhibition.

[7] After moving to Moscow in 1949,[11] Petrosian's career as a chess player advanced rapidly and his results in Soviet events steadily improved.

He seemed content drawing against weaker players and maintaining his title of Grandmaster rather than improving his chess or making an attempt at becoming World Champion.

Although his consistent playing ensured decent tournament results, it was looked down upon by the public and by Soviet chess media and authorities.

[13] Near the end of the event, journalist Vasily Panov wrote the following comment about the tournament contenders: "Real chances of victory, besides Botvinnik and Smyslov, up to round 15, are held by Geller, Spassky and Taimanov.

I deliberately exclude Petrosian from the group, since from the very first rounds the latter has made it clear that he is playing for an easier, but also honourable conquest—a place in the interzonal quartet.

"[14] This period of complacency ended with the 1957 USSR Championship, where out of 21 games played, Petrosian won seven, lost four, and drew the remaining 10.

Although this result was only good enough for seventh place in a field of 22 competitors, his more ambitious approach to tournament play was met with great appreciation from the Soviet chess community.

He went on to win his first USSR Championship in 1959, and later that year in the Candidates Tournament he defeated Paul Keres with a display of his often-overlooked tactical abilities.

[13] After playing in the 1962 Interzonal in Stockholm, Petrosian qualified for the Candidates Tournament in Curaçao along with Pal Benko, Miroslav Filip, Bobby Fischer, Efim Geller, Paul Keres, Viktor Korchnoi, and Mikhail Tal.

Although responses to Fischer's allegations were mixed, FIDE later adjusted the rules and format to try to prevent future collusion in the Candidates.

[16] Having won the Candidates Tournament, Petrosian earned the right to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik for the title of World Chess Champion in a 24-game match.

[18] Petrosian won the match against Botvinnik with a final score of 5 to 2 with 15 draws, securing the title of World Champion.

[19] Upon becoming World Champion, Petrosian campaigned for the publication of a chess newspaper for the entire Soviet Union, rather than just in Moscow.

Petrosian defended his title by winning rather than drawing the match,[21] a feat that had not been accomplished since Alexander Alekhine defeated Efim Bogoljubov in the 1934 World Championship.

[22] However, Spassky defeated Efim Geller, Bent Larsen, and Viktor Korchnoi in the next candidates cycle, earning a rematch with Petrosian, in 1969.

It was the continuation of a bitter feud between the two, dating back at least to their 1974 Candidates semifinal match in which Petrosian withdrew after five games while trailing 1½–3½ (+1−3=1).

At this point Botvinnik spoke on his behalf, stating that Petrosian only attacked when he felt secure, and his greatest strength was in defence.

[23] Some of his late successes included victories at Lone Pine 1976 and in the 1979 Paul Keres Memorial tournament in Tallinn (12/16 without a loss, ahead of Tal, Bronstein, and others).

These were edited by his wife Rona and published posthumously, in Russian under the title Шахматные лекции Петросяна (1989) and in English as Petrosian's Legacy (1990).

In 1987, World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov unveiled a memorial at Petrosian's grave which depicts the laurel wreath awarded to Chess World Champion and an image contained within a crown of the sun shining above the twin peaks of Mount Ararat – the national symbol of Petrosian's Armenian homeland.

[38] His Euroteams results follow: Petrosian was a conservative, cautious, and highly defensive chess player who was strongly influenced by Aron Nimzowitsch's idea of prophylaxis.

"[39] He was considered to be the hardest player to beat in the history of chess by the authors of a 2004 book,[40] and future World Champion Vladimir Kramnik called him "the first defender with a capital D".

"[39] He has been described as a centipede lurking in the dark,[39] a tiger looking for the opportunity to pounce, a python who slowly squeezes his victims to death,[6] and as a crocodile who waits for hours to make a decisive strike.

[48] His 1971 Candidates Tournament match with Viktor Korchnoi featured so many monotonous draws that the Russian press began to complain.

However, Svetozar Gligorić described Petrosian as being "very impressive in his incomparable ability to foresee danger on the board and to avoid any risk of defeat.

"[6] Another consequence of Petrosian's style of play was that he did not score many victories, which in turn meant he seldom won tournaments even though he often finished second or third.

By sacrificing the exchange 'just like that', for certain long term advantages, in positions with disrupted material balance, he discovered latent resources that few were capable of seeing and properly evaluating.

Faced with these threats, Petrosian devised a plan to maneuver his knight to the square d5, where it would be prominently placed in the centre and blockade the advance of White's pawns.