Timucua

At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000.

[1][2][page needed] The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

The name "Timucua" (recorded by the French as Thimogona but this is likely a misprint for Thimogoua) came from the exonym used by the Saturiwa (of what is now Jacksonville) to refer to the Utina, another group to the west of the St. Johns River.

The word "Timucuan" may derive from "Thimogona" or "Tymangoua", an exonym used by the Saturiwa chiefdom of present-day Jacksonville for their enemies, the Utina, who lived inland along the St. Johns River.

[11] De Soto was in a hurry to reach the Apalachee domain, where he expected to find gold and sufficient food to support his army through the winter, so he did not linger in Timucua territory.

[14][15] In 1564, French Huguenots led by René Goulaine de Laudonnière founded Fort Caroline in present-day Jacksonville and attempted to establish further settlements along the St. Johns River.

After initial conflict, the Huguenots established friendly relations with the local natives in the area, primarily the Timucua under the cacique Saturiwa.

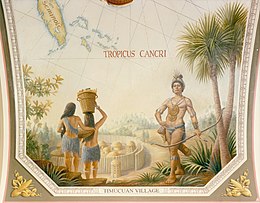

Sketches of the Timucua drawn by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues, one of the French settlers, have proven valuable resources for modern ethnographers in understanding the people.

The next year the Spanish under Pedro Menéndez de Avilés surprised the Huguenots and ransacked Fort Caroline, killing everyone but 50 women and children and 26 escapees.

In 1703, Governor James Moore led a force of colonists from Carolina with allied Creek, Catawba, and Yuchi and launched slave raids against the Timucua, killing and enslaving hundreds of them.

[25] The Western Timucua lived in the interior of the upper Florida peninsula, extending to the Aucilla River on the west and into Georgia to the north.

[27] A chiefdom in central Florida (in southeastern Lake or southwestern Orange counties) led by Urriparacoxi may have spoken Timucua.

[29] Based on a vocabulary list collected from a man named Lamhatty in 1708, Swanton classified the Tawasa language as a dialect of Timucuan.

[30] The largest and best known of the eastern Timucua groups were the Mocama, who lived in the coastal areas of what are now Florida and southeastern Georgia, from St. Simons Island to south of the mouth of the St. Johns River.

[34] European contact with the Eastern Timucua began in 1564 when the French Huguenots under René Goulaine de Laudonnière established Fort Caroline in Saturiwa territory.

The important Mission San Juan del Puerto was established at their main village; it was here that Francisco Pareja undertook his studies of the Timucua language.

The Ibi tribe lived inland from the Yufera, and had 5 towns located 14 leagues (about 50 miles) from Cumberland Island; like the Icafui and Cascangue they spoke the Itafi dialect.

[35] Three major Western Timucua groups, the Potano, Northern Utina, and Yustaga, were incorporated into the Spanish mission system in the late 16th and 17th centuries.

[36][6][24] The Potano lived in north central Florida, in an area covering Alachua County and possibly extending west to Cofa at the mouth of the Suwannee River.

The Northern Utina appear to have been less integrated than other Timucua tribes, and seem to have been organized into several small local chiefdoms, with the leader of one being recognized as paramount chief.

They maintained higher population levels significantly later than other Timucua groups, as their less frequent contact with Europeans kept them freer of introduced diseases.

Hann has argued that the chiefdom of Mocoso, located near the mouth of the Alafia River on the eastern shore of Tampa Bay in the 16th century, was Timucuan.

[39] Some scholars such as Julian Granberry, have suggested that the Tawasa people of Alabama spoke a language related to Timucua based on lexical similarities.

Others like Hann have cast doubt on this theory on the basis that only some words appear to be cognates, and that the Tawasa are never described as Timucua in the historical record despite frequent European encounters with them.

The western Timucua game was evidently less associated with religious significance, violence, and fraud than the Apalachee version, and as such missionaries had a much more difficult time convincing them to give it up.

The Timucua of northeast Florida (the Saturiwa and Agua Dulce tribes) at the time of first contact with Europeans lived in villages that typically contained about 30 houses, and 200 to 300 people.

In addition to agriculture, the Timucua men would hunt game (including alligators, manatees, and maybe even whales); fish in the many streams and lakes in the area; and collect freshwater and marine shellfish.

The women gathered wild fruits, palm berries, acorns, and nuts; and baked bread made from the root koonti.

Measurement of skeletons exhumed from beneath the floor of a presumed Northern Utina mission church (tentatively identified as San Martín de Timucua) at the Fig Springs mission site yielded a mean height of 64 inches (163 cm) for nine adult males and 62 inches (158 cm) for five adult women.

This is largely due to the work of Francisco Pareja, a Franciscan missionary at San Juan del Puerto, who in the 17th century produced a grammar of the language, a confessional, three catechisms in parallel Timucua and Spanish, as well as a newly-discovered Doctrina.