Telmatobius culeus

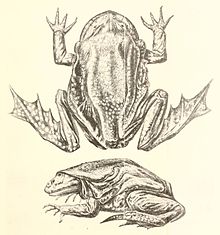

Titicaca water frogs of the largest and typical form, upon which the species was first described, usually have a snout–to–vent length of 7.5 to 17 cm (3.0–6.7 in) and weigh less than 0.4 kg (0.9 lb).

These tend to be smaller in size with a snout–to–vent length of 4 to 8.9 cm (1.6–3.5 in) and historically they were recognized as separate species (T. albiventris and T. crawfordi), but there are extensive individual variations (sometimes even at a single location), no clear limits between the forms (they intergrade) and taxonomic reviews have found that all are variants of the Titicaca water frog.

[18][21] Animals in coastal southernmost Lake Titicaca typically have striped thighs and relatively bright orange underparts.

[6][21] Adults of the typical form generally live deeper than 10 m (33 ft) in Lake Titicaca itself,[5] but the maximum limit is unknown.

[23] While exploring this lake in a mini submarine, Jacques Cousteau filmed individuals and their prints in the bottom silt at 120 m (400 ft), which is the record depth for any species of frog.

[16] The Titicaca water frog mostly feeds on amphipods (especially Hyalella) and snails (especially Heleobia and Biomphalaria),[17] but other food items are insects and tadpoles.

[4][21][19] In captivity, the tadpoles will feed on a range of tiny animals, such as copepods, water fleas, small worms and aquatic insect larvae.

[1] It was once common, with a survey in the late 1960s by Jacques Cousteau and colleagues counting 200 individuals in an only 1 acre (0.4 ha) plot of the huge lake.

[3] The causes of the precarious status of the Titicaca water frog are over-collecting for human consumption, pollution and introduced trout, and it may also be threatened by disease.

[22] Whether this reporting was incomplete or there has been a significant change is unclear, but by the 2000s tens of thousands were caught for food and traditional medicine each year,[32] and even though now illegal the trade has to some extent continued.

Additionally, nutrient-rich pollution from agriculture can cause algae blooms where oxygen levels plummet, asphyxiating the fully aquatic frog.

It has been observed that small Titicaca water frogs may appear in the vicinity of an affected area later, possibly recolonizing it.

[1][29] Lake Saracocha was home to Titicaca water frogs of the "albiventris" form, but they have not been found in later surveys and it is suspected that introduced trout were implicated in their apparent disappearance from this location.

[6] Rainbow trout was introduced on a US initiative from their original North American range to Lake Titicaca in 1941–42 to aid the local fisheries that had relied on the smaller native fish.

[4][31] Conservation projects specifically aimed at the Titicaca water frog have been initiated, some of them in cooperation between Bolivia and Peru, including population monitoring, studies to find the reason for the mass deaths and efforts to reduce the demand for the species as a food/traditional medicine.

[33][34][35][44] Education projects have resulted in some former frog poachers instead becoming part of a handicraft collective that provides a small alternative income.

[31] The possibility of offering ecotours where tourists can snorkel in a wetsuit and see the frogs is being considered at Isla de la Luna (where the species is still quite common), and a pilot project related to this was completed in 2017.

[45] Following its rapid decline in the wild, it was decided in the early 2000s that a secure captive population should be established, which may form the basis for future reintroductions into places where it has disappeared.

[34][35][44] Early captive breeding attempts were unsuccessful;[4] the only partial success was a few tadpoles hatched at the Bronx Zoo in the United States in the 1970s, but they did not metamorphose into frogs.

[23][47][48] The breeding center in Bolivia is supported by Berlin Zoo, Germany,[15] and also involves several other threatened Bolivian frogs.

[49] As a result of disagreement between the museum that provided space for it and the local biologists running it, it was briefly put on pause in 2018,[29] but has since been continued.

[48] The first successful captive breeding outside its native South America happened at the Denver Zoo in 2017–2018 (first tadpoles in 2017, first metamorphosis into young frogs in 2018).