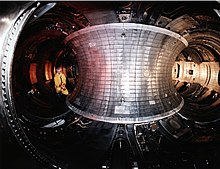

Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor

The Japanese JT-60 is very similar to the TFTR, both tracing their design to key innovations introduced by Shoichi Yoshikawa (1934-2010)[3] during his time at PPPL in the 1970s.

However, with magnetic confinement reactors you avoid the problem of having to find a material that can withstand the high temperatures of nuclear fusion reactions.

The heating current is induced by the changing magnetic fields in central induction coils and exceeds a million amperes.

In 1968, the now-annual meeting was held in Novosibirsk, where the Soviet delegation surprised everyone by claiming their tokamak designs had reached performance levels at least an order of magnitude better than any other device.

The claims were initially met with skepticism, but when the results were confirmed by a UK team the next year, this huge advance led to a "virtual stampede" of tokamak construction.

ST's computerized diagnostics allowed it to quickly match the Soviet results, and from that point, the entire fusion world was increasingly focused on this design over any other.

An added benefit was that as the minor axis increased, confinement time improved for the simple reason that it took longer for the fuel ions to reach the outside of the reactor.

[2] After a number of modifications to the beam injection system, the newly equipped PLT began setting records and eventually made several test runs at 60 million K, more than enough for a fusion reactor.

Notable among the attendees was Marshall Rosenbluth, a theorist who had a habit of studying machines and finding a variety of new instabilities that would ruin confinement.

[7] Bob Hirsch, who recently took over the DOE steering committee, wanted to build the test machine at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), but others in the department convinced him it would make more sense to do so at PPPL.

[8] As PLT continued to generate better and better results, in 1978 and 79, additional funding was added and the design amended to reach the long-sought goal of "scientific breakeven" when the amount of power produced by the fusion reactions in the plasma was equal to the amount of power being fed into it to heat it to operating temperatures.

[11] These demonstrated that the system could reach the goals of the initial 1976 design; the performance when running on deuterium was such that if tritium was introduced it was expected to produce about 3.5 MW of fusion power.

In April 1986, TFTR experiments demonstrated the last two of these requirements when it produced a fusion triple product of 1.5 x 1014 Kelvin seconds per cubic centimeter, which is close to the goal for a practical reactor and five to seven times what is needed for breakeven.

In July 1986, TFTR achieved a plasma temperature of 200 million kelvin (200 MK), at that time the highest ever reached in a laboratory.

The reasons for these problems were intensively studied over the following years, leading to a new understanding of the instabilities of high-performance plasmas that had not been seen in smaller machines.

Although it became clear that TFTR would not reach break-even, experiments using tritium began in earnest in December 1993, the first such device to move primarily to this fuel.