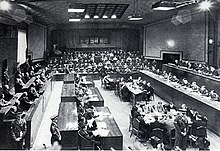

International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The Potsdam Declaration (July 1945) had stated, "stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners," though it did not specifically foreshadow trials.

On April 25, in accordance with the provisions of Article 7 of the CIMTFE, the original Rules of Procedure of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East with amendments were promulgated.

The indictment accused the defendants of promoting a scheme of conquest that:[C]ontemplated and carried out ... murdering, maiming and ill-treating prisoners of war (and) civilian internees ... forcing them to labor under inhumane conditions ... plundering public and private property, wantonly destroying cities, towns and villages beyond any justification of military necessity; (perpetrating) mass murder, rape, pillage, brigandage, torture and other barbaric cruelties upon the helpless civilian population of the over-run countries.The chief prosecutor, Joseph B. Keenan, issued a press statement along with the indictment: "War and treaty-breakers should be stripped of the glamour of national heroes and exposed as what they really are—plain, ordinary murderers."

Any possible evidence that would incriminate Emperor Hirohito and his family was excluded from the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, as the United States believed it needed him to maintain order in Japan and achieve their postwar objectives.

[15] The prosecution team relied on the doctrine of command responsibility, which obviated the need to prove the various alleged atrocities were the result of the defendants' illegal orders.

Part of Article 13 of the Charter provided that evidence against the accused could include any document "without proof of its issuance or signature" as well as diaries, letters, press reports, and sworn or unsworn out-of-court statements relating to the charges.

[18] The prosecution argued that a 1927 document known as the Tanaka Memorial showed that a "common plan or conspiracy" to commit "crimes against peace" bound the accused together.

Justice Henri Bernard of France argued that the tribunal's course of action was flawed due to Hirohito's absence and the lack of sufficient deliberation by the judges.

He concluded that Japan's declaration of war "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices"[23] and that a "verdict reached by a Tribunal after a defective procedure cannot be a valid one."

"It is well-nigh impossible to define the concept of initiating or waging a war of aggression both accurately and comprehensively," wrote Justice Bert Röling of the Netherlands in his dissent.

MacArthur, afraid of embarrassing and antagonizing the Japanese people, defied the wishes of President Truman and barred photography of any kind, instead bringing in four members of the Allied Council to act as official witnesses.

The charges covered a wide range of crimes including prisoner abuse, rape, sexual slavery, torture, ill-treatment of laborers, execution without trial, and inhumane medical experiments.

As Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, MacArthur gave immunity to Shiro Ishii and all members of the bacteriological research units in exchange for germ warfare data based on human experimentation.

[32] Justice Radhabinod Pal argued that the exclusion of Western colonialism and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from the list of crimes and the lack of judges from the vanquished nations on the bench signified the "failure of the Tribunal to provide anything other than the opportunity for the victors to retaliate".

Ben Bruce Blakeney, an American defense counsel for Japanese defendants, argued that "[i]f the killing of Admiral Kidd by the bombing of Pearl Harbor is murder, we know the name of the very man who[se] hands loosed the atomic bomb on Hiroshima," although Pearl Harbor was classified as a war crime under the 1907 Hague Convention, as it happened without a declaration of war and without a just cause for self-defense.

[34] Indian jurist Radhabinod Pal raised substantive objections in a dissenting opinion: he found the entire prosecution case to be weak regarding the conspiracy to commit an act of aggressive war, which would include the brutalization and subjugation of conquered nations.

[36][37] Herbert Bix explained, "The Truman Administration and General MacArthur both believed the occupation reforms would be implemented smoothly if they used Hirohito to legitimise their changes.

[39] Before the war crimes trials actually convened, SCAP, the International Prosecution Section (IPS), and court officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the imperial family from being indicted, but also to skew the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the emperor.

High officials in court circles and the Japanese government collaborated with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals.

People arrested as Class A suspects and incarcerated in the Sugamo Prison solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility.

[39] According to historian Herbert Bix, Brigadier General Bonner Fellers "immediately on landing in Japan went to work to protect Hirohito from the role he had played during and at the end of the war" and "allowed the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the emperor would be spared from indictment.

He argued that with MacArthur's full approval, the prosecution effectively acted as "a defense team for the emperor," who was presented as "an almost saintly figure" let alone someone culpable of war crimes.

Judge-in-Chief Webb declared, "No ruler can commit the crime of launching aggressive war and then validly claim to be excused for doing so because his life would otherwise have been in danger ...

"[22] Justice Henri Bernard of France concluded that Japan's declaration of war "had a principal author who escaped all prosecution and of whom in any case the present Defendants could only be considered as accomplices.

In 1981 John W. Powell published an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists detailing the experiments of Unit 731 and its open-air tests of germ warfare on civilians.

[46] Forty-two suspects, such as Nobusuke Kishi, who later became Prime Minister, and Yoshisuke Aikawa, head of Nissan, were imprisoned in the expectation that they would be prosecuted at a second Tokyo Tribunal but they were never charged.

Under Article 11 of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed on September 8, 1951, Japan accepted the jurisdiction of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

The parole for war criminals movement was driven by two groups: people who had "a sense of pity" for the prisoners demanded, "Just set them free" (tonikaku shakuho o) regardless of how it is done.

Araki Sadao, Hiranuma Kiichirô, Hoshino Naoki, Kaya Okinori, Kido Kôichi, Ôshima Hiroshi, Shimada Shigetarô, and Suzuki Teiichi were released on parole in 1955.

[50] Those enshrined include Hideki Tōjō, Kenji Doihara, Iwane Matsui, Heitarō Kimura, Kōki Hirota, Seishirō Itagaki, Akira Mutō, Yosuke Matsuoka, Osami Nagano, Toshio Shiratori, Kiichirō Hiranuma, Kuniaki Koiso and Yoshijirō Umezu.