Rumpelstiltskin

[2] In order to appear superior, a miller brags to the king and people of his kingdom by claiming his daughter can spin straw into gold.

[note 2] When she has given up all hope, a little imp-like man appears in the room and spins the straw into gold in return for her necklace of glass beads.

While she is sobbing alone in the room, the little imp appears again and promises that he can spin the straw into gold for her, but the girl tells him she has nothing left with which to pay.

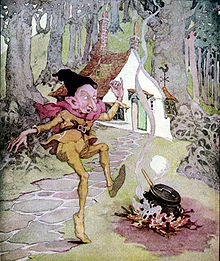

But before the final night, she wanders into the woods[note 5] searching for him and comes across his remote mountain cottage and watches, unseen, as he hops about his fire and sings.

When the imp comes to the queen on the third day, after first feigning ignorance, she reveals his name, Rumpelstiltskin, and he loses his temper at the loss of their bargain.

In the oral version originally collected by the Brothers Grimm, Rumpelstiltskin flies out of the window on a cooking ladle.

– discuss] A possible early literary reference to the tale appears in Dionysius of Halicarnassus's Roman Antiquities, in the 1st century AD.

[5] The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures: Tom Tit Tot[6] in the United Kingdom (from English Fairy Tales, 1890, by Joseph Jacobs); Whuppity Stoorie in Scotland (from Robert Chambers's Popular Rhymes of Scotland, 1826); Gilitrutt in Iceland;[7][8] and The Lazy Beauty and her Aunts in Ireland (from The Fireside Stories of Ireland, 1870 by Patrick Kennedy), though subsequent research [9] has revealed an earlier published version called The White Hen[10] by Ellen Fitzsimon.

[11] The story also appears as جعيدان (Joaidane "He who talks too much") in Arabic; Хламушка (Khlamushka "Junker") in Russia; Rumplcimprcampr, Rampelník or Martin Zvonek in the Czech Republic; Martinko Klingáč in Slovakia; "Cvilidreta" in Croatia; Ruidoquedito ("Little noise") in South America; Pancimanci in Hungary (from 1862 folktale collection by László Arany[12]); Daiku to Oniroku (大工と鬼六 "The carpenter and the ogre") in Japan and Myrmidon in France.

[26][note 6] The meaning is similar to rumpelgeist ("rattle-ghost") or poltergeist ("rumble-ghost"), a mischievous spirit that clatters and moves household objects.

Thus a rumpelstilt or rumpelstilz was also known by such names as pophart or poppart,[22] that makes noises by rattling posts and rapping on planks.

In Italian, the creature is usually called Tremotino, which is probably formed from the world tremoto, which means "earthquake" in Tuscan dialect, and the suffix "-ino", which generally indicates a small and/or sly character.

For Hebrew, the poet Avraham Shlonsky composed the name עוּץ־לִי גּוּץ־לִי Utz-li gutz-li, a compact and rhymy touch to the original sentence and meaning of the story, "My-Adviser My-Midget", from יוֹעֵץ, yo'etz, "adviser", and גּוּץ, gutz, "squat, dumpy, pudgy (about a person)"), when using the fairy-tale as the basis of a children's musical, now a classic among Hebrew children's plays.

The value and power of using personal names and titles is well established in psychology, management, teaching and trial law.