Treasury of Atreus

The tomb was first excavated in the 19th century, when parts of the marble sculptures of its façade were removed by the British aristocrat Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin and the Ottoman governor Veli Pasha.

Throughout the 20th century, the British School at Athens made a series of excavations in and around the tomb, led by Alan Wace, which primarily aimed to settle the difficult question of the date of its construction.

In the version of the myth recounted by Hyginus, Atreus and his brother Thyestes killed their half-brother Chrysippus by casting him into a well out of jealousy, urged on by their mother.

The tomb was visible in Antiquity, but not associated with Atreus or Agamemnon when Pausanias visited in the 2nd century CE, since he describes the graves of both rulers as being within the walls of Mycenae.

[17] It follows the typical tripartite division of these tombs into a narrow rectangular passageway (dromos), joined by a deep doorway (stomion) to a burial chamber (thalamos) surmounted by a corbelled dome.

[18] On top of this doorway are two lintel blocks, the innermost of which is 8 m in length, 5 m in width and 1.2 m thick: with a weight of around 120 tons, it is the heaviest single piece of masonry known from Greek architecture[26] and may have required up to 1,000 people to transport it to the tomb.

[37] Traces of nails hammered into the interior have been recovered, which have been interpreted as evidence for decorations, perhaps golden rosettes, once hung from the inside dome.

In particular, Wright draws attention to the resemblance between the relieving triangle and the sculpted relief of the Lion Gate, and the heavy use of conglomerate on the tomb, which is used within the citadel to accentuate key architectural features, particularly column and anta bases, thresholds and door jambs.

[43] It has also been suggested that the tapering sides and inward slant of the doorway may have been inspired by Ancient Egyptian architecture, while the running-spiral motif on the upper half-columns may trace back to Minoan art.

[51] In 1918, however, Wace published an article entitled 'The Pre-Mycenaean Pottery of the Mainland'[53] along with Carl Blegen, whose own excavations at Korakou in Corinthia in 1915–1916 had convinced him that substantial differences existed between 'Minoan' and 'Helladic' culture in the Late Bronze Age.

[55] Mycenaean culture, they argued, was 'not merely transplanted from Crete, but [was] the fruit of the cultivated Cretan graft set on the wild stock of the mainland'.

[60] This chronological disagreement, and the associated implication that the monumentality and elaboration of Mycenae's funerary forms had increased over the Late Helladic period — which was seen to contradict the idea of the site having been dominated by Cretan rulers[61] — was dubbed the 'Helladic Heresy' by John Percival Droop.

[64] This was primarily based on the findings of his 1939 excavation, which showed that the dromos had been dug through the so-called 'Bothros deposit', which included LH IIIA1 material, providing a terminus post quem for its construction.

[69] Scholars generally consider that the Treasury of Atreus was the penultimate tholos constructed at Mycenae, ahead of the Tomb of Clytemnestra.

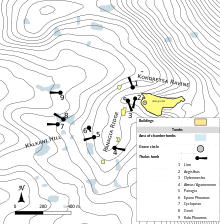

The Treasury of Atreus is located to the west side of the modern road leading to the citadel, approximately 500 m south-southwest of the Lion Gate.

[81] The remains of a seventh-century BCE krater decorated with the image of a horse, found beside the retaining wall of the tumulus, has been taken as evidence of cult activity at the tomb.

[90] Hunt also noted that the tomb was not intact, but open to the elements, and that 'floods of rain' and ingress of debris had made access difficult.

[94] Elgin also had parts of the columns flanking the doorway removed and shipped to England,[93] along with the fragmentary gypsum reliefs of bulls,[95] and architectural drawings made of the tomb by Sebastiano Ittar.

[99] Veli Pasha sold some artefacts to the British MPs and antiquarians John Nicholas Fazakerley and Henry Gally Knight, and removed four large fragments of the semi-engaged columns beside the doorway.

[100][g] Sligo described the columnar fragments as 'trifles', but had them shipped to his estate at Westport House in County Mayo, Ireland, where they were discovered in a basement by his grandson, George Browne, in 1904.

[h] In 1876, he excavated in the side chamber, finding a small pit of unknown purpose;[105] Alan Wace later suggested that it was the base for a column which was never put in.

[106] Between 1876 and 1879, Panagiotis Stamatakis cleared the debris from the dromos and entrance of the tomb,[103] recovering fragments of sculpture believed to have come from the relieving triangle.

[28]In 1920 and 1921, archaeologists of the British School at Athens under Alan Wace made small-scale excavations in the tomb for the purposes of establishing its date,[19] including a trench in the dromos.

[107] During the campaigns of 1920–1923, which had originally intended to excavate the seven thus-far unexcavated tholoi (that is, all except 'Atreus' and 'Clytemnestra'), Wace had the first architectural plans of the tomb drawn up by Piet de Jong.

[108] The 1939 excavation also showed that the dromos had been dug through the so-called 'Bothros deposit', which included LH IIIA1 material, providing a terminus post quem for its construction.