Nisse (folklore)

A nisse (Danish: [ˈne̝sə], Norwegian: [ˈnɪ̂sːə]), tomte (Swedish: [ˈtɔ̂mːtɛ]), tomtenisse, or tonttu (Finnish: [ˈtontːu]) is a household spirit from Nordic folklore which has always been described as a small human-like creature wearing a red cap and gray clothing, doing house and stable chores, and expecting to be rewarded at least once a year around winter solstice (yuletide), with the gift of its favorite food, the porridge.

The term nisse in the native Norwegian is retained in Pat Shaw Iversen's English translation (1960), appended with the parenthetical remark that it is a household spirit.

[27] The Norsk Allkunnebok encyclopedia states less precisely that nisse was introduced from Denmark relatively late, whereas native names found in Norway such as tomte, tomtegubbe, tufte, tuftekall, gardvord, etc., date much earlier.

[32][33] According to Grimm nisse was a form of Niels (or German: Niklas[e]), like various house sprites[f] that adopted human given names,[32][28][g] and was therefore cognate to St. Nicholas, and related to the Christmas gift-giver.

[35][45][46] Regionally in Uppland Sweden is gårdsrå ("yard-spirit"), which being a rå often takes on a female form, which might relate to Western Norwegian garvor (gardvord).

[50][51] However there is caution expressed by linguist Oddrun Grønvik against completely equating the tomte/nissse with the mound dwellers of lore, called the haugkall or haugebonde (from the Old Norse haugr 'mound'),[52] although the latter has become indistinguishable with tuss, as evident from the form haugtuss.

Another near synonym is the drage-dukke, where dukke denotes a "dragger" or "drawer, puller" (of luck or goods delivered to the beneficiary human), which is distinguishable from a nisse since it is considered not to haunt a specific household.

[46] The story of propitiating a household deity for boons in Iceland occurs in the "Story of Þorvaldr Koðránsson the Far-Travelled" (Þorvalds þættur víðförla) and the Kristni saga where the 10th century figure attended to his father Koðrán giving up worship of the heathen idol (called ármaðr or 'year-man' in the saga: spámaðr or 'prophet' in the [Þáttr]]) embodied in stone;[55] this has been suggested as a precursor to the nisse in the monograph study by Henning Frederik Feilberg,[56] though there are different opinions on what label or category should be applied to this spirit (e.g., alternatively as Old Norse landvættr "land spirit").

[59] Feilberg made the fine point of distinction that tomte actually meant a planned building site (where as tun was the plot with a house already built on it), so that the Swedish tomtegubbe, Norwegian tuftekall, tomtevætte, etc.

[60] The thrust of Feilberg's argument considering the origins of the nisse was a combination of a nature spirit and an ancestral ghost (of the pioneer who cleared the land) guarding the family or particular plot.

[67] Several helper-demons were illustrated in the Swedish writer Olaus Magnus's 1555 work, including the center figure of a spiritual being laboring at a stable by night (cf.

[76][71][35] Later folklore says that a tomte is the soul of a slave during heathen times, placed in charge of the maintenance of the household's farmland and fields while the master was away on viking raids, and was duty-bound to continue until doomsday.

[64] In one tale localized at Oxholm [da], the nisse (here called the gaardbuk) falsely announces a cow birthing to the girl assigned to care for it, then tricks her by changing into the shape of a calf.

She stuck him with a pitchfork which the sprite counted as three blows (per each prong), and avenged the girl by making her lie precarious on a plank on the barn's ridge while she was sleeping.

The offering (called gifwa dem lön or "give them a reward") used to be pieces of wadmal (coarse wool), tobacco, and a shovelful of dirt.

It was not only a servant who ate up the porridge meant for the sprite that incurred its wrath,[95] but the nisse was so fastidious that if it was not prepared or presented correctly using butter, he still got angry enough to retaliate.

[113] Conversely, the commonplace motif where the "House spirit leaves when gift of clothing is left for it"[u] might be exhibited: According to one Swedish tale, a certain Danish woman (danneqwinna) noticed that her supply of meal she sifted seemed to last unusually long, although she kept consuming large amounts of it.

[126] In one anecdote, two Swedish neighboring farmers owned similar plots of land, the same quality of meadow and woodland, but one living in a red-colored, tarred house with well-kept walls and sturdy turf roof grew richer by the year, while the other living in a moss-covered house, whose bare walls rotted, and the roof leaked, grew poorer each year.

[77][129][130] A tusse in a Norwegian tale also reverses all the goods (both fodder and food) he had carried from elsewhere after being laughed at for huffing and heaving just a ear of barley.

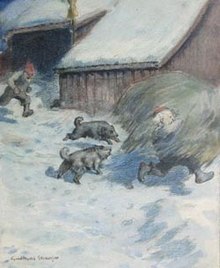

One of his pranks played on the milkmaid is to hold down the hay so firmly the girl is not able to extract it, and abruptly let go so she falls flat on her back; the pleased nisse then explodes into laughter.

[126] The stable-hand needed to remain punctual and feed the horse (or cattle) both at 4 in the morning and 10 at night, or risk being thrashed by the tomte upon entering the stable.

[133][134] The phenomenon of various "elves" (by various names) braiding "elflocks" on the manes of horses is widespread across Europe, but is also attributed to the Norwegian nisse, where it is called the "nisse-plaits" (nisseflette) or "tusse-plaits" (tusseflette), and taken as a good sign of the sprite's presence.

[135][136] Similar superstition regarding tomte (or nisse) is known to have been held in the Swedish-American community, with the taboo that the braid must be unraveled with fingers and never cut with scissors.

English puck), and so on and so forth are grouped together with the Scandinavian nisse or nisse-god-dreng ("good-lad") in similar lists compiled by T. Crofton Croker (1828) and William John Thoms (1828).

[69] In Denmark, it was during the 1840s the farm's nisse became julenisser, the multiple-numbered bearers of Yuletide presents, through the artistic depictions of Lorenz Frølich (1840), Johan Thomas Lundbye (1845), and H. C. Ley (1849).

[162] Herman Hofberg [sv]'s anthology of Swedish folklore (1882), illustrated by Nyström and other artists, writes in the text that the tomte wears a "pointy red hat" ("spetsig röd mössa").

[164] The Danish julemand impersonated by the fake-bearded father of the family wearing gray kofte (glossed as a cardigan (sweater) [no; cardigan] or peasant's frock), red hat, black belt, and wooden shoes full of straw was relatively a new affair as of the early 20th century,[165] and deviates from the traditional nisse in many ways, for instance, the nisse of old lore is beardless like a youth or child.

[citation needed] In the modern conception, the jultomte, Julenisse or Santa Claus, enacted by the father or uncle, etc., in disguise, will show up and deliver as Christmas gift-bringer.

[177] When adapting the mainly English-language concept of tomten having helpers (sometimes in a workshop), tomtenisse can also correspond to the Christmas elf, either replacing it completely, or simply lending its name to the elf-like depictions in the case of translations.

The appearance traditionally ascribed to a nisse or tomte resembles that of the garden gnome figurine for outdoors,[178] which are in turn, also called trädgårdstomte in Swedish,[179] havenisse in Danish, hagenisse in Norwegian[180][181] and puutarhatonttu in Finnish.