Tonkin Affair

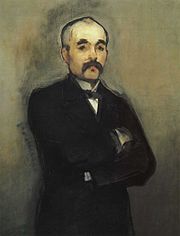

It effectively destroyed the political career of the French prime minister, Jules Ferry, and abruptly ended the string of Republican governments inaugurated several years earlier by Léon Gambetta.

The retreat, which threw away the gains of the February Lạng Sơn Campaign, was ordered by Lieutenant-Colonel Paul Gustave Herbinger, the acting commander of the 2nd Brigade, less than a week after General François de Négrier's defeat at the Battle of Bang Bo (24 March 1885).

Facing greatly superior numbers, short of ammunition, and exhausted from a series of earlier actions, Colonel Herbinger has informed me that the position was untenable and that he has been forced to fall back tonight on Dong Song and Thanh Moy.

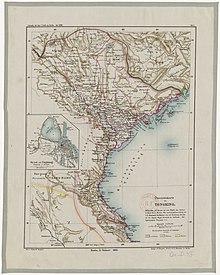

The enemy continues to grow stronger on the Red River, and it appears that we are facing an entire Chinese army, trained in the European style and ready to pursue a concerted plan.

I hope in any event to be able to hold the entire Delta against this invasion, but I consider that the government must send me reinforcements (men, ammunition, and pack animals) as quickly as possible.

[1] The news contained in the 'Lạng Sơn telegram', as it was immediately dubbed, ignited a political crisis in Paris:There was enormous feeling throughout France.

All the newspapers were full of accusations against the Cabinet, of false accounts of the 'bitter combats' that the 2nd Brigade, enveloped by the Chinese, must have fought to disengage, of fears for the entire expeditionary corps, whose situation was depicted as tragic.

In the House, the deputies who were systematically opposed to our establishment in Tonkin were jubilant, and the proponents of a colonial policy did not dare defend their views of the previous day.

In the afternoon he entered the chamber amid the disapproving silence of his supporters and a storm of imprecations and insults from his opponents, led by Georges Clemenceau.

Eventually, when he could again make himself heard, Ferry demanded an extraordinary credit of 200 million francs, to be split equally between the army and navy ministries.

As Ferry sought to leave the Palais Bourbon to return to the Elysée Palace, he had to run the gauntlet of a furious crowd of demonstrators gathered together by Paul de Cassagnac.

The news of the cabinet's fall had gone round Paris like wildfire, and in front of the palais Bourbon an excited mob, estimated by journalists at around 20,000 people, thronged the pont de la Concorde.

The sudden and ignominious end of Jules Ferry's second administration removed the remaining obstacles to a peace settlement between France and China.

In December 1885, in the so-called 'Tonkin Debate', Henri Brisson's administration was only able to secure fresh credits for the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps by the very narrowest of margins.

The collapse of Ferry's ministry was a major political embarrassment for the proponents of the policy of French colonial expansion first championed in the 1870s by Léon Gambetta.

French Indochina was consolidated under a single administration just two years later, while in Africa, military commanders like Joseph Gallieni and Louis Archinard continually pressured local states, regardless of the political climate in Paris.

Large trading houses, such as Maurel and Prom company, continued to expand their overseas operations, and demand military support for this expansion.

The formal creation in 1894 of the French Colonial Union, a political pressure group funded by such interests, marked the end of the post-Tonkin climate in Paris, which was, as such, short-lived.