Tool bit

Back rake is to help control the direction of the chip, which naturally curves into the work due to the difference in length from the outer and inner parts of the cut.

Nose radius varies depending on the machining operations like roughing, semi-finishing or finishing and also on the component material being cut: steel, cast iron, aluminium and others.

All the other angles are for clearance in order that no part of the tool besides the actual cutting edge can touch the work.

The cutting edge is usually either screwed or clamped on (in this case it is called an insert), or brazed on to a steel shank (this is usually only done for carbide).

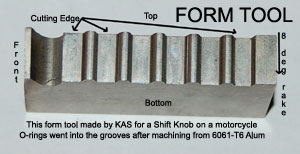

Before the use of form tools, diameters were turned by multiple slide and turret operations, and thus took more work to make the part.

For example, a form tool can turn many diameters and in addition can also cut off the part in a single operation and eliminate the need to index the turret.

For single-spindle machines, bypassing the need to index the turret can dramatically increase hourly part production rates.

The supporting tool holder can then be made from a tougher steel, which besides being cheaper is also usually better suited to the task, being less brittle than the cutting-edge materials.

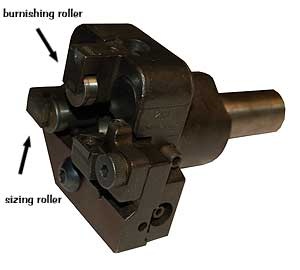

The tool holders may also be designed to introduce additional properties to the cutting action, such as: Note that since stiffness (rather than strength) is usually the design driver of a tool holder, the steel used does not need to be particularly hard or strong as there is relatively little difference between the stiffnesses of most steel alloys.

As the tool bit puts a lateral deflecting force on the workpiece, the follower rest opposes it, providing rigidity.

Shapers, slotters, and planers often employ a kind of toolholder called a clapper box that swings freely on the return stroke of the ram or bed.

In fact, good machinists were expected to have blacksmithing knowledge, and although the chemistry and physics of the heat treatment of steel were not well understood (as compared with today's sciences), the practical art of heat treatment was quite advanced, and something that most skilled metalworkers were comfortably acquainted with.

The exact details of the heat treatment and tip geometry were a matter of individual experience and preference.

A substantial technological advance occurred in the 1890–1910 period, when Frederick Winslow Taylor applied scientific methods to the study of tool bits and their cutting performance (including their geometry, metallurgy, and heat treatment, and the resulting speeds and feeds, depths of cut, metal-removal rates, and tool life).

Along with Maunsel White and various assistants, he developed high-speed steels (whose properties come from both their alloying element mixtures and their heat treatment methods).

His cutting experiments chewed through tons of workpiece material, consumed thousands of tool bits, and generated mountains of chips.

After Taylor, it was no longer taken for granted that the black art of individual craftsmen represented the highest level of metalworking technology.

Although diamond turning had been around for a long time, it was not until these new, expensive metals came about that the idea of cutting inserts became commonly applied in machining.