Boiler

In some cases byproduct fuel such as the carbon monoxide rich offgasses of a coke battery can be burned to heat a boiler; biofuels such as bagasse, where economically available, can also be used.

[citation needed] For much of the Victorian "age of steam", the only material used for boilermaking was the highest grade of wrought iron, with assembly by riveting.

This iron was often obtained from specialist ironworks, such as those in the Cleator Moor (UK) area, noted for the high quality of their rolled plate, which was especially suitable for use in critical applications such as high-pressure boilers.

In the 20th century, design practice moved towards the use of steel, with welded construction, which is stronger and cheaper, and can be fabricated more quickly and with less labour.

Wrought iron boilers corrode far more slowly than their modern-day steel counterparts, and are less susceptible to localized pitting and stress-corrosion.

Although such heaters are usually termed "boilers" in some countries, their purpose is usually to produce hot water, not steam, and so they run at low pressure and try to avoid boiling.

The source of heat for a boiler is combustion of any of several fuels, such as wood, coal, oil, or natural gas.

[8] Historically, boilers were a source of many serious injuries and property destruction due to poorly understood engineering principles.

Thin and brittle metal shells can rupture, while poorly welded or riveted seams could open up, leading to a violent eruption of the pressurized steam.

At best, this increases energy costs and can lead to poor quality steam, reduced efficiency, shorter plant life and unreliable operation.

Extremely large boilers providing hundreds of horsepower to operate factories can potentially demolish entire buildings.

As the resulting "dry steam" is much hotter than needed to stay in the vaporous state it will not contain any significant unevaporated water.

However, the overall energy efficiency of the steam plant (the combination of boiler, superheater, piping and machinery) generally will be improved enough to more than offset the increased fuel consumption.

The design of any superheated steam plant presents several engineering challenges due to the high working temperatures and pressures.

In the event of a major rupture of the system, an ever-present hazard in a warship during combat, the enormous energy release of escaping superheated steam, expanding to more than 1600 times its confined volume, would be equivalent to a cataclysmic explosion, whose effects would be exacerbated by the steam release occurring in a confined space, such as a ship's engine room.

Also, small leaks that are not visible at the point of leakage could be lethal if an individual were to step into the escaping steam's path.

Special methods of coupling steam pipes together are used to prevent leaks, with very high pressure systems employing welded joints to avoided leakage problems with threaded or gasketed connections.

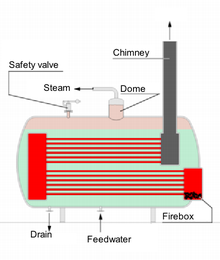

Early boilers provided this stream of air, or draught, through the natural action of convection in a chimney connected to the exhaust of the combustion chamber.

This is because natural draught is subject to outside air conditions and temperature of flue gases leaving the furnace, as well as the chimney height.

(preserved, Historic Silver Mine in Tarnowskie Góry Poland ).

( United States ).