Tosafot

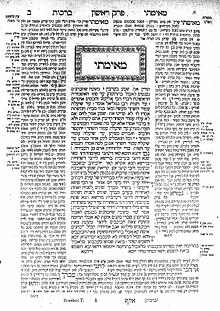

They take the form of critical and explanatory glosses, printed, in almost all Talmud editions, on the outer margin and opposite Rashi's notes.

Many of them, including Heinrich Graetz, think the glosses are so-called as additions to Rashi's commentary on the Talmud.

[citation needed] Others, especially Isaac Hirsch Weiss, object that many tosafot — particularly those of Isaiah di Trani — have no reference to Rashi.

The Tosafot do not constitute a continuous commentary, but rather (like the "Dissensiones" to the Roman Code of the first quarter of the twelfth century) deal only with difficult passages of the Talmud.

The rules are certainly not gathered together in one series, as they are, for instance, in Maimonides' introduction to the Mishnah; they are scattered in various parts, and their number is quite considerable.

With regard to method, it should be said that the Tosafot of Touques (see below) concern particularly the casuistic interpretation of the traditional law, but do not touch halakhic decisions.

While tosafot began to be written in Germany at the same time as in France, the French tosafists always predominated numerically.

The first tosafot recorded are those written by Rashi's two sons-in-law, Meïr b. Samuel of Ramerupt (RaM) and Judah ben Nathan (RIBaN), and by a certain R.

[5] But Isaac ben Asher's tosafot were revised by his pupils, who, according to Rabbeinu Tam,[6] sometimes ascribed to their teacher opinions which were not his.

Samson's fellow pupil Judah b. Isaac of Paris (Sir Leon) was also very active; he wrote tosafot to several Talmudic treatises, of which those to Berakhot were published at Warsaw (1863); some of those to 'Abodah Zarah are extant in manuscript.

Among the many French tosafists deserving special mention was Samuel ben Solomon of Falaise (Sir Morel), who, owing to the destruction of the Talmud in France in his time, relied for the text entirely upon his memory.

[8] The edited tosafot owe their existence particularly to Samson of Sens and to the following French tosafists of the thirteenth century: (1) Moses of Évreux, (2) Eliezer of Touques, and (3) Perez ben Elijah of Corbeil.

It has been said that the first German tosafist, Isaac b. Asher ha-Levi, was the head of a school, and that his pupils, besides composing tosafot of their own, revised his.

When the fanaticism of the French monasteries and the judgement of King Louis IX brought about the destruction of the Talmud, the writing of tosafot in France soon ceased.

The publisher of that edition was a nephew of Rabbi Moshe of Spires (Shapiro) who was of the last generation of Tosafists and who initiated a project of writing a final compilation of the Tosafos.

The Tosafot quote principally Rashi (very often under the designation qonṭres "pamphlet" (Rashi initially published his commentary in pamphlets), many of the ancient authorities (as Kalonymus of Lucca, Nathan ben Jehiel, and Chananel ben Chushiel ), some contemporary scholars (as Abraham ben David, Maimonides, Abraham ibn Ezra, and others), and about 130 German and French Talmudists of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

Many of the last-named are known as authors of general Talmudic works, as, for instance, Eliezer ben Nathan of Mainz, Judah of Corbeil, and Jacob of Coucy; but many of them are known only through their being quoted in the Tosafot, as in the case of an Eliezer of Sens, a Jacob of Orléans, and many Abrahams and Isaacs.

According to Joseph Colon[13] and Elijah Mizraḥi,[14] Moses wrote his glosses on the margin of Isaac Alfasi's "Halakhot," probably at the time of the burning of the Talmud.

It must be premised, however, that the Tosafot of Touques did not remain untouched; they were revised afterward and supplemented by the glosses of later tosafists.

Zunz[15] thinks that the Tosafot of Sens may be referred to under this title; but the fact that Abraham b. David was much earlier than Samson of Sens leads to the supposition that the glosses indicated are those of previous tosafists, as Rabbeinu Tam, Isaac b. Asher ha-Levi, and Isaac b. Samuel ha-Zaḳen and his son.

This term is used by Joseph Colon[16] and by Jacob Baruch Landau[17] and may apply to Talmudic novellae by Spanish authors.

Jeshuah b. Joseph ha-Levi, for instance, applies the term "tosafot" to the novellae of Isaac ben Sheshet.

The term may designate either the tosafot of Samuel b. Meïr and Moses of Évreux, or glosses to Alfasi's Halakot.

They are so called by Betzalel Ashkenazi; he included many fragments of them in his Shitah Mekubetzet, to Bava Metzia, Nazir, etc.

3), besides the old tosafot to Yoma by Moses of Coucy,[29] there are single tosafot to sixteen treatises—Shabbat, Rosh HaShanah, Megillah, Gittin, Bava Metzia, Menaḥot, Bechorot, Eruvin, Beitzah, Ketubot, Kiddushin, Nazir, Bava Batra, Horayot, Keritot, and Niddah.

[citation needed] The Tosafot shelanu are printed in most Talmud editions, in the column farther from the binding.

The main text in the middle is the text of the Talmud itself. To the right, on the inner margin of the page, is Rashi's commentary; to the left, on the outer margin, the Tosafot