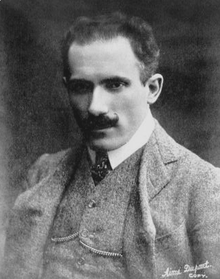

Arturo Toscanini

He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orchestral detail and sonority, and his eidetic memory.

Later in his career, he was appointed the first music director of the NBC Symphony Orchestra (1937–1954), and this led to his becoming a household name, especially in the United States, through his radio and television broadcasts and many recordings of the operatic and symphonic repertoire.

Although he had no conducting experience, Toscanini was eventually persuaded by the musicians to take up the baton at 9:15 pm, and led a performance of the two-and-a-half hour opera, completely from memory.

[5] He also returned to his chair in the cello section, and participated as cellist in the world premiere of Verdi's Otello (La Scala, Milan, 1887) under the composer's supervision.

In December 1920, he brought the La Scala Orchestra to the United States on a concert tour during which time he made his first recordings for the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, New Jersey.

[12] During his career as an opera conductor, Toscanini collaborated with such artists as Enrico Caruso, Feodor Chaliapin, Ezio Pinza, Giovanni Martinelli, Geraldine Farrar and Aureliano Pertile.

"[15] At a memorial concert for Italian composer Giuseppe Martucci on May 14, 1931, at the Teatro Comunale in Bologna, Toscanini was ordered to begin by playing Giovinezza, but he flatly refused, despite the presence of fascist communications minister Costanzo Ciano in the audience.

[18] The infamous dry acoustics of the specially built radio studio gave the orchestra, as heard on early broadcasts and recordings, a harsh, flat quality; some remodeling in 1942, at Leopold Stokowski's insistence, added a bit more reverberation.

[20][non-primary source needed] Toscanini was sometimes criticized for neglecting American music, but on November 5, 1938, he conducted the world premieres of two orchestral works by Samuel Barber, Adagio for Strings and Essay for Orchestra.

He also conducted broadcast performances of Copland's El Salón México; Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue with soloists Earl Wild and Benny Goodman and Piano Concerto in F with pianist Oscar Levant; and music by several other American composers, including some marches of John Philip Sousa.

All of these performances were eventually released on records and CD by RCA Victor, thus enabling modern listeners an opportunity to hear what an opera conducted by Toscanini sounded like.

[citation needed] With the help of his son Walter, Toscanini spent his remaining years evaluating and editing tapes and transcriptions of his broadcast performances with the NBC Symphony for possible future release on records.

[citation needed] Toscanini suffered a stroke on New Year's Day 1957, and he died on January 16, at the age of 89 at his home in the Riverdale section of the Bronx in New York City.

[citation needed] In his will, he left his baton to his protégée Herva Nelli, who sang in the broadcasts of Otello, Aida, Falstaff, the Verdi Requiem, and Un ballo in maschera.

As his biographer Harvey Sachs wrote: "He believed that a performance could not be artistically successful unless unity of intention was first established among all the components: singers, orchestra, chorus, staging, sets, and costumes.

[citation needed] Toscanini was especially famous for his performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Richard Strauss, Debussy and his own compatriots Rossini, Verdi, Boito and Puccini.

O'Connell and others often complained the Maestro was little interested in the details of recorded sound and, as Harvey Sachs wrote, Toscanini was frequently disappointed that the microphones failed to pick up everything he heard as he led the orchestra.

RCA Victor apparently was now hesitant to promote the orchestra and recordings since it was now under contract to arch-rival Columbia and declared the defective Philadelphia masters unsalvageable.

As for the historic nature of the recordings, even on the first RCA Victor compact disc issue, released in 1991, some of the sides have considerable surface noise and some distortion, especially during the louder passages.

Sachs wrote that an Italian journalist, Raffaele Calzini, said Toscanini told him, "My son Walter sent me the test pressing of the [Beethoven] Ninth from America; I want to hear and check how it came out, and possibly to correct it.

Two days after the final concert, Guido Cantelli took the podium in a hastily organized session to record the Franck Symphony in D minor, for RCA Victor using the same microphone and equipment set-up put in place for the Maestro.

These films, issued by RCA on VHS tape and laser disc and on DVD by Testament, provide unique video documentation of the passionate yet restrained podium technique for which he was well known.

That same year it released a Beethoven bicentennial set that included the 1935 Missa Solemnis with the Philharmonic and LPs of the 1948 televised concert of the ninth symphony taken from an FM radio transcription, complete with Ben Grauer's comments.

[citation needed] Because the Arturo Toscanini Society was nonprofit, Key said he believed he had successfully bypassed both copyright restrictions and the maze of contractual ties between RCA and the Maestro's family.

But classical-LP profits were low enough even in 1970, and piracy by fly-by-night firms so prevalent within the industry at that time (an estimated $100 million in tape sales for 1969 alone), that even a benevolent buccaneer outfit like the Arturo Toscanini Society had to be looked at twice before it could be tolerated.

[citation needed] On March 15, 1952, Toscanini conducted the Symphonic Interlude from Franck's Rédemption; Sibelius's En saga; Debussy's "Nuages" and "Fêtes" from Nocturnes; and the overture of Rossini's William Tell.

[citation needed] In December 1943, Toscanini appeared in a 31-minute film for the United States Office of War Information titled Hymn of the Nations, directed by Alexander Hammid.

[57][full citation needed] Some online critics such as Peter Gutmann have dismissed much of what was written about Toscanini during his lifetime and for about ten years afterwards as "adoring puffery".

During Toscanini's middle years, however, such now widely accepted composers as Richard Strauss and Claude Debussy, whose music the conductor held in very high regard, were considered to be radical and modern.

[citation needed] In 1967, The Bell Telephone Hour telecast a program entitled Toscanini: The Maestro Revisited, written and narrated by New York Times music critic Harold C. Schonberg, and featuring commentary by conductors Eugene Ormandy, George Szell, Erich Leinsdorf and Milton Katims (who had played viola in the NBC Symphony Orchestra).