Toshiyori

The benefits are considerable, as toshiyori are guaranteed employment until the mandatory retirement age of 65 and are allowed to run and coach in heya (sumo stables), with a comfortable yearly salary averaging around ¥15 million.

[1] Originating from a tradition dating back to the Edo period, the position of toshiyori is founded on a system set up at a time when several sumo associations managed Japan's professional wrestling.

[2] Prior to its appearance in the sumo world during the 17th century, the term toshiyori was used primarily in the Edo period and before to refer to central and provincial government administrators as well as community leaders, with a meaning of "senior citizen".

[11] The function of sumo elder was born with the organization of the first tournaments authorized by the municipal administrations of major Japanese cities.

[14] Eventually, the mix of disgraced rōnins with the commoners who took part in the contests of strength of the street tournaments created many conflicts over betting money.

[16] During the Keian era, public order became so disturbed that, in 1648, the Edo authorities issued an edict banning street sumo and matches organized to raise funds during festivities.

[18] Because he allowed the return of matches by proposing a new etiquette associated with the conduct of fights, Ikazuchi was recognized as a key interlocutor by the authorities, which earned him a tournament organizer's license referring to him as a "toshiyori", one of the first mentions of the term in sumo.

[21] The practice of allowing former wrestlers to coach new aspirants was eventually capped in 1927, when the sumo associations based in Osaka and Tokyo merged.

During the Edo period, any wrestler or referee of any rank could inherit the name of his master, under whose protection he had placed himself, in order to perpetuate his legacy.

During the Edo period, when the transmission of the status became established, virtually any wrestler or referee could inherit a share without paying any money, but simply taking responsibility for the livehood of his master and his wife.

[30] In 1976, an internal rule defined that only Japanese nationals could become elders, with the unofficial aim of preventing foreigners from having a lasting influence on the sport by occupying decision-making positions within the association.

[38][39][40] In January 2014, the association shifted to a Public Interest Incorporated Foundation [ja] effectively implementing the change from March to coincide with new board of directors elections after difficult negotiations over the status of toshiyori.

[49] Only wrestlers who have reached the ranks of san'yaku (meaning yokozuna, ōzeki, sekiwake and komusubi) and have held it for at least one tournament are directly entitled to apply to remain as an executive within the association.

[53] On his retirement, some elders suggested that conditions be added to the inheritance of the name, such as not operating a stable for a period of ten years, but these were not included in the final pledge.

[29] The limited number of shares, their unequal distribution between clans and the inability of some younger generations of wrestlers to find coaching positions were cited as fears that the sport was suffering from atrophy.

[8] After the association became a Public Interest Incorporated Foundation, the sale of shares was theoretically prohibited, under threats of disciplinary action up to and including expulsion.

[70] Retired wrestlers can't call on banks and take out loans, as the Sumo Association prohibits the use of shares as collateral for debts.

[28] Due to speculation, it is generally unprofitable to invest in an elder share, as the salary associated with the status never makes up for the amount spent to obtain the title when the wrestler retired.

[29] A large number of wrestlers eligible for a share inheritance are unable to remain in the sport as coaches, precisely because they are in high demand and therefore rare and expensive.

[52] An exception to the normal acquisition is made for the most successful rikishi, with era-defining yokozuna being offered a "single generation" or "lifetime" elder share, called ichidai toshiyori kabu (一代年寄株).

[52][55][73] This process allows a wrestler to stay as an elder without having to use a traditional share in the association, and enter his retirement duties with his ring name.

[78][79] Since all the holders were yokozuna who had completed more than twenty yūshō (championship victories), this prerequisite became a traditional milestone for obtaining the single generation share.

[45] In particular, several informal comments made to the press referred to the concern of certain Sumo Association executives about Hakuhō's attitude, resurrecting fears of once again having to deal with internal tumult like that caused by Takanohana Kōji, who had enjoyed the honors of the ichidai toshiyori kabu.

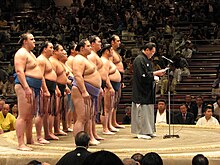

[111] The toshiyori who sit as fuku-riji and riji must first be elected by all the elders assembled in a board of trustees called hyōgiin-kai (評議員会).

This committee, called hyōgi-in (評議員), is made up equally of retired wrestlers (who were not re-employed under the san'yo consultant system) elected within the association and personalities appointed by the ministry.

[121] A wrestler is sometimes even considered a second-rate elder if he hasn't achieved a sufficiently high rank in his active career, and this consideration sometimes prevents him from occupying important positions in the association's organization after his retirement.

[127][128][129] It seems that in the event of a breach of their duty to supervise their wrestlers, and particularly in the context of media coverage of violence scandals, the penalty regularly imposed on a toshiyori is a reduction in salary and a two-rank demotion in the hierarchy.

[131] The third most important punishment for a master, demotion was used for the first time on a former yokozuna against former Wajima (then known as Hanakago) after he had put up his share in the Association as collateral on a loan.

[138] After their final retirement at the age of 65, many elders remain informally attached to their former stables, where they provide advice to active wrestlers in addition to the master who has inherited their share.

The latter having been built up during their wrestling careers, and for most of them since their teens, it became apparent that requiring the services of foreign personalities would involve training in the codes of the sport and in special relationships of trust, which would take too much time compared to self-management.