Total internal reflection

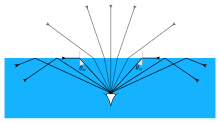

For example, the water-to-air surface in a typical fish tank, when viewed obliquely from below, reflects the underwater scene like a mirror with no loss of brightness (Fig. 1).

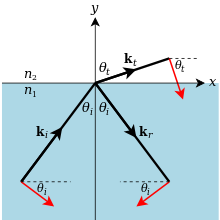

[8] This result has the form of "Snell's law", except that we have not yet said that the ratio of velocities is constant, nor identified θ1 and θ2 with the angles of incidence and refraction (called θi and θt above).

Hence, for isotropic media, total internal reflection cannot occur if the second medium has a higher refractive index (lower normal velocity) than the first.

When standing beside an aquarium with one's eyes below the water level, one is likely to see fish or submerged objects reflected in the water-air surface (Fig. 1).

[12] The field of view above the water is theoretically 180° across, but seems less because as we look closer to the horizon, the vertical dimension is more strongly compressed by the refraction; e.g., by Eq.

What looks like a broad horizontal stripe on the right-hand wall consists of the lower edges of a row of orange tiles, and their reflections; this marks the water level, which can then be traced across the other wall.

The space above the water is not visible except at the top of the frame, where the handles of the ladder are just discernible above the edge of Snell's window – within which the reflection of the bottom of the pool is only partial, but still noticeable in the photograph.

One can even discern the color-fringing of the edge of Snell's window, due to variation of the refractive index, hence of the critical angle, with wavelength (see Dispersion).

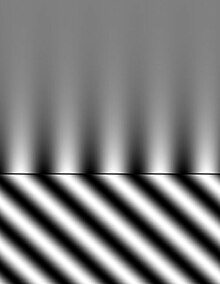

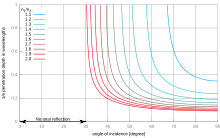

Thus, using mostly qualitative reasoning, we can conclude that total internal reflection must be accompanied by a wavelike field in the "external" medium, traveling along the interface in synchronism with the incident and reflected waves, but with some sort of limited spatial penetration into the "external" medium; such a field may be called an evanescent wave.

[1][20] The term frustrated TIR also applies to the case in which the evanescent wave is scattered by an object sufficiently close to the reflecting interface.

This effect, together with the strong dependence of the amount of scattered light on the distance from the interface, is exploited in total internal reflection microscopy.

[22] Due to the wave nature of matter, an electron has a non-zero probability of "tunneling" through a barrier, even if classical mechanics would say that its energy is insufficient.

[18][19] Similarly, due to the wave nature of light, a photon has a non-zero probability of crossing a gap, even if ray optics would say that its approach is too oblique.

For the p components, this article adopts the convention that the positive directions of the incident, reflected, and transmitted fields are inclined towards the same medium (that is, towards the same side of the interface, e.g. like the red arrows in Fig. 11).

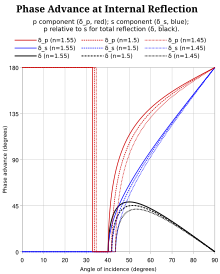

which gives a phase advance of[34] Making the same substitution in (14), we find that ts has the same denominator as rs with a positive real numerator (instead of a complex conjugate numerator) and therefore has half the argument of rs, so that the phase advance of the evanescent wave is half that of the reflected wave.

This device performs the same function as a birefringent quarter-wave plate, but is more achromatic (that is, the phase shift of the rhomb is less sensitive to wavelength).

The consequent scattering of the evanescent wave (a form of frustrated TIR), makes the objects appear bright when viewed from the "external" side.

[63] A gonioscope, used in optometry and ophthalmology for the diagnosis of glaucoma, suppresses TIR in order to look into the angle between the iris and the cornea.

The gonioscope replaces the air with a higher-index medium, allowing transmission at oblique incidence, typically followed by reflection in a "mirror", which itself may be implemented using TIR.

The surprisingly comprehensive and largely correct explanations of the rainbow by Theodoric of Freiberg (written between 1304 and 1310)[66] and Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (completed by 1309),[67] although sometimes mentioned in connection with total internal reflection (TIR), are of dubious relevance because the internal reflection of sunlight in a spherical raindrop is not total.

[Note 16] But, according to Carl Benjamin Boyer, Theodoric's treatise on the rainbow also classified optical phenomena under five causes, the last of which was "a total reflection at the boundary of two transparent media".

[69] Theodoric having fallen into obscurity, the discovery of TIR was generally attributed to Johannes Kepler, who published his findings in his Dioptrice in 1611.

[71] Christiaan Huygens, in his Treatise on Light (1690), paid much attention to the threshold at which the incident ray is "unable to penetrate into the other transparent substance".

(12) above, there is no threshold value of the angle θi beyond which κ becomes infinite; so the penetration depth of the evanescent wave (1/κ) is always non-zero, and the external medium, if it is at all lossy, will attenuate the reflection.

In 1813, Biot established that one case studied by Arago, namely quartz cut perpendicular to its optic axis, was actually a gradual rotation of the plane of polarization with distance.

[97] In 1817 he noticed that plane-polarized light seemed to be partly depolarized by total internal reflection, if initially polarized at an acute angle to the plane of incidence.

[102] The experimental confirmation was reported in a "postscript" to the work in which Fresnel expounded his mature theory of chromatic polarization, introducing transverse waves.

[111] Fresnel's deduction of the phase shift in TIR is thought to have been the first occasion on which a physical meaning was attached to the argument of a complex number.

[115] In the 20th century, quantum electrodynamics reinterpreted the amplitude of an electromagnetic wave in terms of the probability of finding a photon.

Research into the more subtle aspects of the phase shift in TIR, including the Goos–Hänchen and Imbert–Fedorov effects and their quantum interpretations, has continued into the 21st century.