Tourism in Libya

[5] As of 2017, governments of the United States,[6] New Zealand,[7] Australia,[8] Canada,[9] Ireland,[10] the United Kingdom,[11] Spain,[12] France,[13] Hungary,[14] Latvia,[15] Germany,[16] Austria,[17] Bulgaria,[18] Norway,[19] Croatia,[20] Romania,[21] Slovenia,[22] Czech Republic,[23] Russia,[24] Denmark,[25] Slovakia,[26] Estonia,[27] Italy,[28] Poland,[29] South Korea,[30] the Republic of China[31] Japan[32] and India advise their citizens against all (or in some cases all but essential) travel to Libya.

It has resulted in delays in tourism development and made it difficult for tourists, who have instead had to travel through an arduous, physically exhausting way into and out of the country through the Tunisia-Libya land border.

The Libyan dinar has highly appreciated, which leads to uncompetitive prices for tourist related services such as accommodation and transportation, compared with neighboring countries.

On 6 May 2006, was created the Hammamet Declaration, a document whose purpose was to harmonize tourism development in the countries of the western Mediterranean basin, taking into account environmental and social differences.

The aim was to create a cultural and ecological tourism that encouraged projects based on the principles of sustainability, respect for the environment and the use of local products.

In 2012 the new government decided to diversify resources and create jobs, the authorities changed the laws and regulations to attract foreign economic investments and make the economy grow.

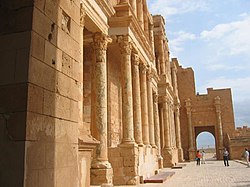

The Roman cities of Sabratha and Leptis Magna in Western Libya and the Greek ruins of Cyrene in the east are big tourist attractions.

Besides the well preserved late 3rd century theatre, that retains its three-storey architectural backdrop, Sabratha has temples dedicated to Liber Pater, Serapis and Isis.

There is a Christian basilica of the time of Justinian and remnants of some of the mosaic floors that enriched elite dwellings of Roman North Africa; the Villa Sileen near Al-Khoms is a good example.

It survived the attention of Spartan colonists, and became a Punic city and eventually part of the new Roman province of Africa around 23 BC.

Cyrenaica became part of the Ptolemaic empire controlled from Alexandria, and became Roman territory in 96 BC when Ptolemy Apion bequeathed Cirenaica to Rome.

The large structure comprises a labyrinth of courtyards, alleyways and houses built up over the centuries with a total area of around 13,000 square metres (140,000 sq ft).

Inside, there is evidence of all the city's (and thus the citadel's) ruling parties: the Turks, Karamanlis, Spaniards, Knights of Malta, Italians and several others who all left their presence in its arts and architecture.

These facilities were built in consultation with UNESCO at enormous cost, and the exhibits within are laid out chronologically, starting with prehistory and ending up with the revolution.

Highlights included the superb pre-historic rock art sites of the Acacus Mountains (contiguous with the Tassili n’Ajjer in adjacent Algeria) and the nearby Mesak Settafet escapement (Wadi Mathendous), Ottoman-era forts in Murzuk, the unique dune-ringed lakes of the Idehan Ubari Sand Sea and the nearby ruins of the Garamantes in the Wadi Eshati.

Independent tourism only emerged in the late 1990s when various, well-connected Libyan middlemen were able to obtain the necessary invite to apply for a visa in one's home country.

Once at the border vehicles had to rent Libyan number plates and buy a locally issued temporary vehicle importation permit, similar to the Egyptian system, except that in Libya the documents were in Arabic and border personnel did not speak European languages so the services of a fixer were needed to clear the border.Up to 2002 it was possible to travel in Libya without an expensive escort from a local tourist agency, but once on the road (and with black market currency bought ner the border), fuel cost just a few pence a litre; among the cheapest in the world.

In the days when this was possible, the remote desert town of Ghat in the far southwest of the Fezzan was the key destination for most travellers, accessed either along the 600-km border track south of Ghadames to Serdeles (Al Awaynat), across the Hamada el Hamra plateau[33] to Idri, or for the intrepid few with a local guide, right through the Ubari Sand Sea to the Ubari–Ghat road along the Wadi Eshati.

From Sabha, travellers could drive east to Waw an Namus volcanic crater, then continue through the Rebiana Sand Sea to Tazirbu for Kufra.

Southeast of Kufra lay the massifs of Jabal Arkanu and Gabal El Uweinat straddling the borders of Egypt and Sudan.

Most European desert tourists, either driving the own vehicles and entering Libya from Tunisia, or flying in to Tripoli for an escorted tour, had more than enough to fill their time visiting the spectacles of the Fezzan.