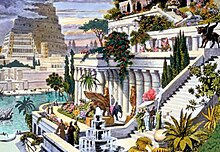

Tower of Babel

[1][2][3][4][5] According to the story, a united human race speaking a single language migrates to Shinar (Lower Mesopotamia),[b] where they agree to build a great city with a tower that would reach the sky.

Yahweh, observing these efforts and remarking on humanity's power in unity, confounds their speech so that they can no longer understand each other and scatters them around the world, leaving the city unfinished.

[7] A similar story is also found in the ancient Sumerian legend, Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, which describes events and locations in southern Mesopotamia.

[9][10] Per the story in Genesis, the city received the name "Babel" from the Hebrew verb bālal,[e] meaning to jumble or to confuse, after Yahweh distorted the common language of humankind.

"[13] Augustine explained this apparent contradiction by arguing that the story "without mentioning it, goes back to tell how it came about that the one language common to all men was broken up into many tongues".

[16] The first century Jewish interpretation found in Flavius Josephus explains the construction of the tower as a hubristic act of defiance against God ordered by the arrogant tyrant Nimrod.

[27] The first century Roman-Jewish author Flavius Josephus similarly explained that the name was derived from the Hebrew word Babel (בבל), meaning "confusion".

In the Sumerian myth Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta,[33] Enmerkar of Uruk is building a massive ziggurat in Eridu and demands a tribute of precious materials from Aratta for its construction, at one point reciting an incantation imploring the god Enki to restore (or in Kramer's translation, to disrupt) the linguistic unity of the inhabited regions—named as Shubur, Hamazi, Sumer, Uri-ki (Akkad), and the Martu land, "the whole universe, the well-guarded people—may they all address Enlil together in a single language.

These events may have influenced later biblical writers during the period of Babylonian captivity, who viewed the city’s fall as a divine act, reinforcing the idea that Babylon’s pride led to its downfall.

The Jewish-Roman historian Flavius Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews (c. 94 CE), recounted history as found in the Hebrew Bible and mentioned the Tower of Babel.

He also gradually changed the government into tyranny, seeing no other way of turning men from the fear of God, but to bring them into a constant dependence on his power... Now the multitude were very ready to follow the determination of Nimrod and to esteem it a piece of cowardice to submit to God; and they built a tower, neither sparing any pains, nor being in any degree negligent about the work: and, by reason of the multitude of hands employed in it, it grew very high, sooner than any one could expect; but the thickness of it was so great, and it was so strongly built, that thereby its great height seemed, upon the view, to be less than it really was.

When God saw this He did not permit them, but smote them with blindness and confusion of speech, and rendered them as thou seest.Rabbinic literature offers many different accounts of other causes for building the Tower of Babel, and of the intentions of its builders.

The passage mentions that the builders spoke sharp words against God, saying that once every 1,656 years, heaven tottered so that the water poured down upon the earth, therefore they would support it by columns that there might not be another deluge (Gen. R.

They were encouraged in this undertaking by the notion that arrows that they shot into the sky fell back dripping with blood, so that the people really believed that they could wage war against the inhabitants of the heavens (Sefer ha-Yashar, Chapter 9:12–36).

Another Muslim historian of the 13th century, Abu al-Fida relates the same story, adding that the patriarch Eber (an ancestor of Abraham) was allowed to keep the original tongue, Hebrew in this case, because he would not partake in the building.

Aside from the Ancient Greek myth that Hermes confused the languages, causing Zeus to give his throne to Phoroneus, Frazer specifically mentions such accounts among the Wasania of Kenya, the Kacha Naga people of Assam, the inhabitants of Encounter Bay in Australia, the Maidu of California, the Tlingit of Alaska, and the K'iche' Maya of Guatemala.

Beginning in Renaissance Europe, priority over Hebrew was claimed for the alleged Japhetic languages, which were supposedly never corrupted because their speakers had not participated in the construction of the Tower of Babel.

Among the candidates for a living descendant of the Adamic language were: Gaelic (see Auraicept na n-Éces); Tuscan (Giovanni Battista Gelli, 1542, Pier Francesco Giambullari, 1564); Dutch (Goropius Becanus, 1569, Abraham Mylius, 1612); Swedish (Olaus Rudbeck, 1675); German (Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, 1641, Schottel, 1641).

The Swedish physician Andreas Kempe wrote a satirical tract in 1688, where he made fun of the contest between the European nationalists to claim their native tongue as the Adamic language.

[53] The primacy of Hebrew was still defended by some authors until the emergence of modern linguistics in the second half of the 18th century, e.g. by Pierre Besnier [fr] (1648–1705) in A philosophicall essay for the reunion of the languages, or, the art of knowing all by the mastery of one (1675) and by Gottfried Hensel (1687–1767) in his Synopsis Universae Philologiae (1741).

(The LXX Bible has two additional names, Elisa and Cainan, not found in the Masoretic text of this chapter, so early rabbinic traditions, such as the Mishna, speak instead of "70 languages".)

Some of the earliest sources for 72 (sometimes 73) languages are the 2nd-century Christian writers Clement of Alexandria (Stromata I, 21) and Hippolytus of Rome (On the Psalms 9); it is repeated in the Syriac book Cave of Treasures (c. 350 CE), Epiphanius of Salamis' Panarion (c. 375) and St. Augustine's The City of God 16.6 (c. 410).

This listing was to prove quite influential on later accounts that made the Lombards and Franks themselves into descendants of eponymous grandsons of Japheth, e.g. the Historia Brittonum (c. 833), The Meadows of Gold by al Masudi (c. 947) and Book of Roads and Kingdoms by al-Bakri (1068), the 11th-century Lebor Gabála Érenn, and the midrashic compilations Yosippon (c. 950), Chronicles of Jerahmeel, and Sefer haYashar.

Other sources that mention 72 (or 70) languages scattered from Babel are the Old Irish poem Cu cen mathair by Luccreth moccu Chiara (c. 600); the Irish monastic work Auraicept na n-Éces; History of the Prophets and Kings by the Persian historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (c. 915); the Anglo-Saxon dialogue Solomon and Saturn; the Russian Primary Chronicle (c. 1113); the Jewish Kabbalistic work Bahir (1174); the Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson (c. 1200); the Syriac Book of the Bee (c. 1221); the Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum (c. 1284; mentions 22 for Shem, 31 for Ham and 17 for Japheth for a total of 70); Villani's 1300 account; and the rabbinic Midrash ha-Gadol (14th century).

A.S. Kline translates Ovid's Metamorphoses 1.151–155 as:[54] Rendering the heights of heaven no safer than the earth, they say the giants attempted to take the Celestial kingdom, piling mountains up to the distant stars.

Then the all-powerful father of the gods hurled his bolt of lightning, fractured Olympus and threw Mount Pelion down from Ossa below.Various traditions similar to that of the tower of Babel are found in Latin America.

The Dominican friar Diego Durán (1537–1588) reported hearing an account about the pyramid from a hundred-year-old priest at Cholula, shortly after the conquest of the Aztec Empire.

[59][further explanation needed] According to David Livingstone, the people he met living near Lake Ngami in 1849 had such a tradition, but with the builders' heads getting "cracked by the fall of the scaffolding".

Frazer moreover cites such legends found among the Kongo people, as well as in Tanzania, where the men stack poles or trees in a failed attempt to reach the Moon.

He notes yet another version current in the Admiralty Islands, where mankind's languages are confused following a failed attempt to build houses reaching to heaven.