Toy theater

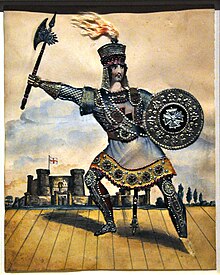

[2][3] The original toy theatres were mass-produced replicas of popular plays, sold as kits that people assembled at home, including stage, scenery, characters and costumes.

Toward the end of the 19th century, European popular drama had shifted its preference to the trend of realism, marking a dramaturgical swing toward psychological complexity, character motivation and settings using ordinary three-dimensional scenic elements.

In 1884 British author Robert Louis Stevenson wrote an essay in tribute of toy theater's tiny grandeur entitled "Penny Plain, Twopence Coloured" in which he extolled the virtues of the dramas supplied by Pollock's.

But after its second wave boom, toy theater fell into a second recession, replaced in the 1950s, by a different box in people's sitting rooms that needed no live operator and whose sets, characters, stories and musical numbers were beamed in electronically from miles away to be projected on the glass of a cathode ray tube: television.

Collectors and traditionalists perform restored versions of Victorian plays while experimental puppeteers push the form's limits, adapting the works of Isaac Babel and Italo Calvino, as well as that of unsung storytellers, friends, neighbors, relatives, and themselves.

Mass-produced toy theaters are usually sold as printed sheets, either in black and white to be colored as desired, or as full-color images of the proscenium, scenery, sets, props and characters.