Tridentine Mass

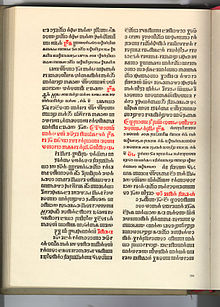

Celebrated almost exclusively in Ecclesiastical Latin, it was the most widely used Eucharistic liturgy in the world from its issuance in 1570 until its replacement by the Mass of Paul VI promulgated in 1969 (with the revised Roman Missal appearing in 1970.

In response to a decision of that council,[7] Pope Pius V promulgated the 1570 Roman Missal, making it mandatory throughout the Latin Church, except in places and religious orders with rites or uses from before 1370.

[15][failed verification] Other names for the edition promulgated by Pope John XXIII in 1962 (the last to bear the indication ex decreto Sacrosancti Concilii Tridentini restitutum) are the Extraordinary Form, or the usus antiquior ("more ancient usage" in Latin ).

However, there have been numerous exceptions, primarily in missionary areas or for ancient churches with an established sacred-language tradition:[23] [24] After the publication of the 1962 edition of the Roman Missal, the 1964 Instruction on implementing the Constitution on Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council laid down that "normally the epistle and gospel from the Mass of the day shall be read in the vernacular".

[33] Outside the Roman Catholic Church: At the time of the Council of Trent, the traditions preserved in printed and manuscript missals varied considerably, and standardization was sought both within individual dioceses and throughout the Latin West.

Pope Pius V accordingly imposed uniformity by law in 1570 with the papal bull "Quo primum", ordering use of the Roman Missal as revised by him.

[34] Beginning in the late 17th century, France and neighbouring areas, such as Münster, Cologne and Trier in Germany, saw a flurry of independent missals published by bishops influenced by Jansenism and Gallicanism.

The General Roman Calendar was revised partially in 1955 and 1960 and completely in 1969 in Pope Paul VI's motu proprio Mysterii Paschalis, again reducing the number of feasts.

It is only one of the three conditions (baptism, right faith and right living) for admission to receiving Holy Communion that the Catholic Church has always applied and that were already mentioned in the early 2nd century by Saint Justin Martyr: "And this food is called among us the Eucharist, of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined" (First Apology, Chapter LXVI).

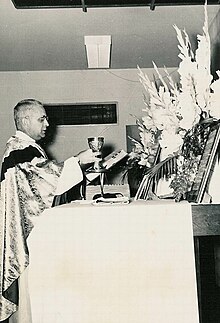

After that, the priest, vested in a cope of the color of the day, while the choir sings an antiphon and a verse of Psalm 50/51 or 117/118, sprinkles with the holy water the altar three times, and then the clergy and the congregation.

After this he ascends to the altar, praying silently "Aufer a nobis, quæsumus, Dómine, iniquitates nostras: ut ad Sancta sanctorum puris mereámur méntibus introíre.

[59] Until 1960, the Tridentine form of the Roman Missal laid down that a candle should be placed at the Epistle side of the altar and that it should be lit at the showing of the consecrated sacrament to the people.

In later editions of the Roman Missal, including that of 1962, the introductory heading of these prayers indicates that they are to be recited pro opportunitate (as circumstances allow),[69] which in practice means that they are merely optional and may be omitted.

Later editions place before these three the Canticle of the Three Youths (Dan)[72] with three collects, and follow them with the Anima Christi and seven more prayers, treating as optional even the three prescribed in the original Tridentine Missal.

[73] From 1884 to 1965, the Holy See prescribed the recitation after Low Mass of certain prayers, originally for the solution of the Roman Question and, after this problem was solved by the Lateran Treaty, "to permit tranquillity and freedom to profess the faith to be restored to the afflicted people of Russia".

The choir sings the Introit, the Kyrie, the Gloria, the Gradual, the Tract or Alleluia, the Credo, the Offertory and Communion antiphons, the Sanctus, and the Agnus Dei.

They argue that many of the changes made to the liturgy in 1955 and onward were largely the work of liturgist Annibale Bugnini, whom traditionalists say was more interested in innovation than the preservation of the apostolic traditions of the Church.

[85] Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, a former Prefect of the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, supported this study with a letter of 25 September 1969 to Pope Paul VI.

[91] Western countries also saw a decline in seminary enrollments and in the number of priests (in the United States, from 1,575 ordinations in 1954 to 450 in 2002), and a general erosion of belief in the doctrines of the Catholic faith.

Following the rise of the Traditionalist Catholic movement in the 1970s, Pope Paul VI reportedly declined to liberalise its use further on the grounds that it had become a politically charged symbol associated with opposition to his policies.

[97] In 1988, following the excommunication of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and the four bishops consecrated by him, the Pope issued the motu proprio Ecclesia Dei, which stated that "respect must everywhere be shown for the feelings of all those who are attached to the Latin liturgical tradition".

The Pope urged bishops to give "a wide and generous application" to the provisions of Quattuor abhinc annos, and established the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei to oversee relations between Rome and Traditionalist Catholics.

[101] In September 2006, the Pontifical Commission Ecclesia Dei established the Institute of the Good Shepherd, made up of former members of the Society of St. Pius X, in Bordeaux, France, with permission to use the Tridentine liturgy.

[104] Following repeated rumours that the use of the Tridentine Mass would be liberalised, the Pope issued a motu proprio called Summorum Pontificum on 7 July 2007,[105] together with an accompanying letter to the world's bishops.

[106] The declaring that "the Roman Missal promulgated by Paul VI is the ordinary expression of the lex orandi (law of prayer) of the Catholic Church of the Latin rite.

He replaced with new rules those of Quattuor Abhinc Annos on use of the older form: essentially, authorization for using the 1962 form for parish Masses and those celebrated on public occasions such as a wedding is devolved from the local bishop to the priest in charge of a church, and "any priest of the Latin rite" may use the 1962 Roman Missal in "Masses celebrated without the people", a term that does not exclude attendance by other worshippers, lay or clergy.

[f] Pope Francis on 16 July 2021 released an Apostolic Letter Motu Proprio, Traditionis custodes, on the use of the Roman Liturgy prior to the Reform of 1970.

[109] Pope Francis added that it is the exclusive competence of the local bishop to authorize the use of the 1962 Roman Missal in his diocese, according to the guidelines of the Apostolic See.

[111] In February 2023, Pope Francis issued a rescript, clarifying that bishops must obtain authorization from the Holy See before granting permission for parish churches to be used for Eucharistic celebrations with the preconciliar rite and before allowing priests ordained after 16 July 2021 to use the 1962 Roman Missal.

[113] In December 2021, additional restrictions and guidelines were issued by the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments in the form of a Responsa ad dubia:[114] In December 2021, in an interview with the National Catholic Register, Arthur Roche, the Prefect for the Congregation in charge of the implementation of Traditionis custodes, reiterated Pope Francis' statement that the Mass according to the Missal promulgated by Paul VI and John Paul II, is "the unique expression of the lex orandi of the Roman Rite".

In the Tridentine Mass the priest should keep his eyes downcast at this point. [ 54 ]