Trans-Alaska Pipeline System

Preconstruction work during 1973 and 1974 was critical and included the building of camps to house workers, construction of roads and bridges where none existed, and carefully laying out the pipeline right of way to avoid difficult river crossings and animal habitats.

However, in building the Alaska Pipeline, engineers faced a wide range of difficulties, stemming mainly from the extreme cold and the difficult, isolated terrain.

The project attracted tens of thousands of workers to Alaska due to high wages, long work hours, and paid-for housing, causing a boomtown atmosphere in Valdez, Fairbanks, and Anchorage.

The pipeline could be extended and used to transport oil produced from controversial proposed drilling projects in the nearby Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR).

The first renewed efforts to identify strategic oil assets were a two pronged survey using bush aircraft, local Inupiat guides, and personnel from multiple agencies to locate reported seeps.

[22] The Manhattan was fitted with an ice-breaking bow, powerful engines, and hardened propellers before successfully traveling the Northwest Passage from the Atlantic Ocean to the Beaufort Sea.

[23] In February 1969, before the SS Manhattan had even sailed from its East Coast starting point, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), an unincorporated joint group created by ARCO, British Petroleum, and Humble Oil in October 1968,[24] asked for permission from the United States Department of the Interior to begin geological and engineering studies of a proposed oil pipeline route from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez, across Alaska.

[27] In June 1969, as the SS Manhattan traveled through the Northwest Passage, TAPS formally applied to the Interior Department for a permit to build an oil pipeline across 800 miles (1,300 km) of public land—from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez.

This report was passed along to the appropriate committees of the U.S. House and Senate, which had to approve the right-of-way proposal because it asked for more land than authorized in the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 and because it would break a development freeze imposed in 1966 by former Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall.

[31] In the fall of 1969, the Department of the Interior and TAPS set about bypassing the land freeze by obtaining waivers from the various native villages that had claims to a portion of the proposed right of way.

By the end of September, all the relevant villages had waived their right-of-way claims, and Secretary of the Interior Wally Hickel asked Congress to lift the land freeze for the entire TAPS project.

[35] After the Department of the Interior was stopped from issuing a construction permit, the unincorporated TAPS consortium was reorganized into the new incorporated Alyeska Pipeline Service Company.

[36] Former Humble Oil manager Edward L. Patton was put in charge of the new company and began to lobby strongly in favor of an Alaska Native claims settlement to resolve the disputes over the pipeline right of way.

[43] Criticisms of the project included its effect on the Alaska tundra, possible pollution, harm to animals, geographic features, and the lack of much engineering information from Alyeska.

[49] Following the Native lawsuit to halt work on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, this precedent was frequently mentioned in debate, causing pressure to resolve the situation more quickly than the 33 years it had taken for the Tlingits to be satisfied.

[52] The issue remained at a standstill until Alyeska began lobbying in favor of a Native claims act in Congress in order to lift the legal injunction against pipeline construction.

[57] To those who argued that the pipeline would irrevocably alter Alaska wilderness, proponents pointed to the overgrown remnants of the Fairbanks Gold Rush, most of which had been erased 70 years later.

[58] Some pipeline opponents were satisfied by Alyeska's preliminary design, which incorporated underground and raised crossings for caribou and other big game, gravel and styrofoam insulation to prevent permafrost melting, automatic leak detection and shutoff, and other techniques.

[72][73] On October 17, 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries announced an oil embargo against the United States in retaliation for its support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

[78] Although the legal right-of-way was cleared by January 1974, cold weather, the need to hire workers, and construction of the Dalton Highway meant work on the pipeline itself did not begin until March.

[88] By 1976, after the town's residents had endured a spike in crime, overstressed public infrastructure, and an influx of people unfamiliar with Alaska customs, 56 percent said the pipeline had changed Fairbanks for the worse.

To meet the demand, a Fairbanks high school ran in two shifts: one in the morning and the other in the afternoon in order to teach students who also worked eight hours per day.

[99] Alyeska and its contractors bought in bulk from local stores, causing shortages of everything from cars to tractor parts, water softener salt, batteries and ladders.

This was exacerbated by the fact that police officers and state troopers resigned in large groups to become pipeline security guards at wages far in excess of those available in public-sector jobs.

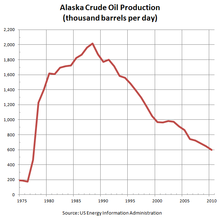

[105] The wealth generated by Prudhoe Bay and the other fields on the North Slope since 1977 is worth more than all the fish ever caught, all the furs ever trapped, all the trees chopped down; throw in all the copper, whalebone, natural gas, tin, silver, platinum, and anything else ever extracted from Alaska too.

The balance sheet of Alaskan history is simple: One Prudhoe Bay is worth more in real dollars than everything that has been dug out, cut down, caught or killed in Alaska since the beginning of time.

[113] Under the latest taxation system, introduced by former governor Sarah Palin in 2007 and passed by the Alaska Legislature that year, the maximum tax rate on profits is 50 percent.

[121] In addition to the Permanent Fund, the state also maintains the Constitutional Budget Reserve, a separate savings account established in 1990 after a legal dispute over pipeline tariffs generated a one-time payment of more than $1.5 billion from the oil companies.

[126] Notable visitors have included Henry Kissinger,[127] Jamie Farr,[127] John Denver,[127] President Gerald Ford,[127] King Olav V of Norway,[128] and Gladys Knight.

[175][176] The largest oil spill involving the main pipeline took place on February 15, 1978, when an unknown individual blew a 1-inch (2.54-centimeter) hole in it at Steele Creek, just east of Fairbanks.