Methods of detecting exoplanets

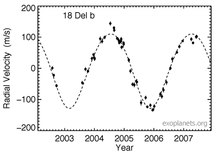

Planets with orbits highly inclined to the line of sight from Earth produce smaller visible wobbles, and are thus more difficult to detect.

[8] Several surveys have taken that approach, such as the ground-based MEarth Project, SuperWASP, KELT, and HATNet, as well as the space-based COROT, Kepler and TESS missions.

In these cases, the maximum transit depth of the light curve will not be proportional to the ratio of the squares of the radii of the two stars, but will instead depend solely on the small fraction of the primary that is blocked by the secondary.

Some of the false positive cases of this category can be easily found if the eclipsing binary system has a circular orbit, with the two companions having different masses.

[22][23][24] A French Space Agency mission, CoRoT, began in 2006 to search for planetary transits from orbit, where the absence of atmospheric scintillation allows improved accuracy.

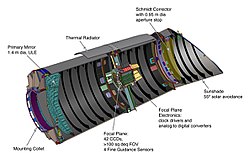

[26] In March 2009, NASA mission Kepler was launched to scan a large number of stars in the constellation Cygnus with a measurement precision expected to detect and characterize Earth-sized planets.

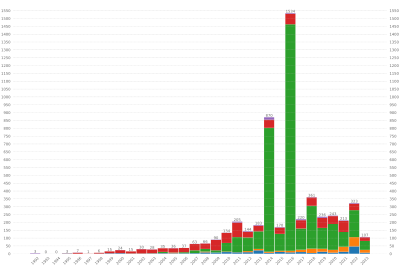

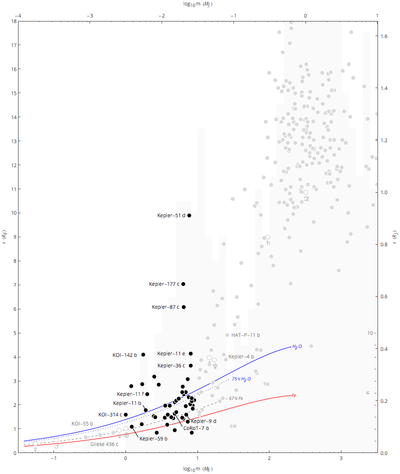

On 5 December 2011, the Kepler team announced that they had discovered 2,326 planetary candidates, of which 207 are similar in size to Earth, 680 are super-Earth-size, 1,181 are Neptune-size, 203 are Jupiter-size and 55 are larger than Jupiter.

Moreover, 48 planet candidates were found in the habitable zones of surveyed stars, marking a decrease from the February figure; this was due to the more stringent criteria in use in the December data.

[34] A separate novel method to detect exoplanets from light variations uses relativistic beaming of the observed flux from the star due to its motion.

It is also capable of detecting mutual gravitational perturbations between the various members of a planetary system, thereby revealing further information about those planets and their orbital parameters.

Since that requires a highly improbable alignment, a very large number of distant stars must be continuously monitored in order to detect planetary microlensing contributions at a reasonable rate.

Successes with the method date back to 2002, when a group of Polish astronomers (Andrzej Udalski, Marcin Kubiak and Michał Szymański from Warsaw, and Bohdan Paczyński) during project OGLE (the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) developed a workable technique.

In addition to the European Research Council-funded OGLE, the Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) group is working to perfect this approach.

It allows nearly continuous round-the-clock coverage by a world-spanning telescope network, providing the opportunity to pick up microlensing contributions from planets with masses as low as Earth's.

[59] The NASA Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope scheduled for launch in 2027 includes a microlensing planet survey as one of its three core projects.

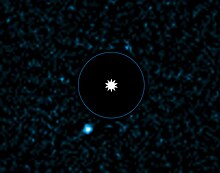

In 2004, a group of astronomers used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope array in Chile to produce an image of 2M1207b, a companion to the brown dwarf 2M1207.

[69][70] On the same day, 13 November 2008, it was announced that the Hubble Space Telescope directly observed an exoplanet orbiting Fomalhaut, with a mass no more than 3 MJ.

On 21 November 2008, three days after acceptance of a letter to the editor published online on 11 December 2008,[72] it was announced that analysis of images dating back to 2003, revealed a planet orbiting Beta Pictoris.

This instrument is designed JPL as a demonstrator for a future large observatory in space that will have the imaging of Earth-like exoplanets as one of its primary science goals.

In 2010, a team from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory demonstrated that a vortex coronagraph could enable small scopes to directly image planets.

[83] Another possibility would be to use a large occulter in space designed to block the light of nearby stars in order to observe their orbiting planets, such as the New Worlds Mission.

The most popular technique is Angular Differential Imaging (ADI), where exposures are acquired at different parallactic angle positions and the sky is left to rotate around the observed central star.

[85] By analyzing the polarization in the combined light of the planet and star (about one part in a million), these measurements can in principle be made with very high sensitivity, as polarimetry is not limited by the stability of the Earth's atmosphere.

Astrometry is the oldest search method for extrasolar planets, and was originally popular because of its success in characterizing astrometric binary star systems.

[118] Non-periodic variability events, such as flares, can produce extremely faint echoes in the light curve if they reflect off an exoplanet or other scattering medium in the star system.

[119][120][121][122] More recently, motivated by advances in instrumentation and signal processing technologies, echoes from exoplanets are predicted to be recoverable from high-cadence photometric and spectroscopic measurements of active star systems, such as M dwarfs.

[130] In March 2019, ESO astronomers, employing the GRAVITY instrument on their Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), announced the first direct detection of an exoplanet, HR 8799 e, using optical interferometry.

[137] The Hubble Space Telescope is capable of observing dust disks with its NICMOS (Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer) instrument.

Therefore, the detection of dust indicates continual replenishment by new collisions, and provides strong indirect evidence of the presence of small bodies like comets and asteroids that orbit the parent star.

[143] This material orbits with a period of around 4.5 hours, and the shapes of the transit light curves suggest that the larger bodies are disintegrating, contributing to the contamination in the white dwarf's atmosphere.