Transtheoretical model

[9] James O. Prochaska of the University of Rhode Island, and Carlo Di Clemente and colleagues developed the transtheoretical model beginning in 1977.

One of the most effective steps that others can help with at this stage is to encourage them to become more mindful of their decision making and more conscious of the multiple benefits of changing an unhealthy behavior.

Achieving a long-term behavior change often requires ongoing support from family members, a health coach, a physician, or another motivational source.

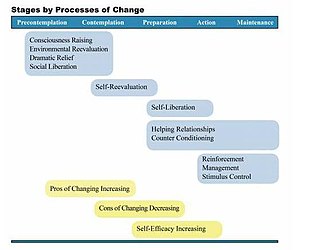

As people move toward Action and Maintenance, they rely more on commitments, counter conditioning, rewards, environmental controls, and support.

[11][nb 5] Decision making was conceptualized by Janis and Mann as a "decisional balance sheet" of comparative potential gains and losses.

[26] Sound decision making requires the consideration of the potential benefits (pros) and costs (cons) associated with a behavior's consequences.

During the change process, individuals gradually increase the pros and decrease the cons forming a more positive balance towards the target behaviour.

Especially all TPB variables (attitude, perceived behaviour control, descriptive and subjective norm) are positively show a gradually increasing relationship to stage of change for bike commuting.

[30][33][34] This core construct is "the situation-specific confidence people have that they can cope with high-risk situations without relapsing to their unhealthy or high risk-habit".

[42] Members of a large New England health plan and various employer groups who were prescribed a cholesterol lowering medication participated in an adherence to lipid-lowering drugs intervention.

The intervention's largest effects were observed among patients with moderate or severe depression, and who were in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stage of change at baseline.

For example, among patients in the Precontemplation or Contemplation stage, rates of reliable and clinically significant improvement in depression were 40% for treatment and 9% for control.

Those randomly assigned to the treatment group received a stage-matched multiple behavior change guide and a series of tailored, individualized interventions for three health behaviors that are crucial to effective weight management: healthy eating (i.e., reducing calorie and dietary fat intake), moderate exercise, and managing emotional distress without eating.

At 24 months, those who were in a pre-Action stage for healthy eating at baseline and received treatment were significantly more likely to have reached Action or Maintenance than the comparison group (47.5% vs. 34.3%).

The treatment also had a significant effect on managing emotional distress without eating, with 49.7% of those in a pre-Action stage at baseline moving to Action or Maintenance versus 30.3% of the comparison group.

This study demonstrates the ability of TTM-based tailored feedback to improve healthy eating, exercise, managing emotional distress, and weight on a population basis.

[46] Multiple studies have found individualized interventions tailored on the 14 TTM variables for smoking cessation to effectively recruit and retain pre-Action participants and produce long-term abstinence rates within the range of 22% – 26%.

[48][49][50] For a summary of smoking cessation clinical outcomes, see Velicer, Redding, Sun, & Prochaska, 2007 and Jordan, Evers, Spira, King & Lid, 2013.

TTM helps guide the treatment process at each stage, and may assist the healthcare provider in making an optimal therapeutic decision.

A number of cross-sectional studies investigated the individual constructs of TTM, e.g. stage of change, decisional balance and self-efficacy, with regards to transport mode choice.

The cross-sectional studies identified both motivators and barriers at the different stages regarding biking, walking and public transport.

[53][57][58][59][60][61] Most intervention studies aim to reduce car trips for commute to achieve the minimum recommended physical activity levels of 30 minutes per day.

[9] Depending on the field of application (e.g. smoking cessation, substance abuse, condom use, diabetes treatment, obesity and travel) somewhat different criticisms have been raised.

[70] A 2010 systematic review of smoking cessation studies under the auspices of the Cochrane Collaboration found that "stage-based self-help interventions (expert systems and/or tailored materials) and individual counselling were neither more nor less effective than their non-stage-based equivalents".

[71] A 2014 Cochrane systematic review concluded that research on the use of TTM stages of change "in weight loss interventions is limited by risk of bias and imprecision, not allowing firm conclusions to be drawn".

A continuous version of the model has been proposed, where each process is first increasingly used, and then decreases in importance, as smokers make progress along some latent dimension.

[74] Within the health research domain, a 2005 systematic review of 37 randomized controlled trials claims that "there was limited evidence for the effectiveness of stage-based interventions as a basis for behavior change.

[76] In diabetes research the "existing data are insufficient for drawing conclusions on the benefits of the transtheoretical model" as related to dietary interventions.

[78] A 2011 Cochrane Systematic Review found that there is little evidence to suggest that using the transtheoretical model stages of change (TTM SOC) method is effective in helping obese and overweight people lose weight.

[79] In this study, the algorithms and questionnaires that researchers used to assign people to stages of change lacked standardisation to be compared empirically, or validated.