South African Republic

Relations between the ZAR and Britain started to deteriorate after the British Cape Colony expanded into the Southern African interior, eventually leading to the outbreak of the First Boer War between the two nations.

Many Boer combatants in the ZAR refused to surrender, leading British commander Lord Kitchener to order the adoption of several scorched-earth policies.

The land area that was once the ZAR now comprises all or most of the provinces of Gauteng, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, and North West in the northeastern portion of the modern-day Republic of South Africa.

The same year, the Volksraad renamed the state to the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek Benoorden de Vaalrivier (South African Republic to the North of the Vaal River).

[7] The name of the South African Republic was of such political significance that on 1 September 1900, the British declared by special proclamation that the name of the country had been changed from Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek to "the Transvaal".

This area was inhabited by the Boers, who, dissatisfied with British rule, decided to leave the colony and move into the hinterland of South Africa in what became the Great Trek.

[11] Confederation of the South African region was thought to be very beneficial for the British, as it would "cheapen the administration of affairs" and reduce the need for imperial money and troops.

Only one year after the Sand Rivers Convention, the Lieutenant-Governor of Natal, Benjamin Pine, reported that the Boers had interpreted the treaty as having placed Zululand under their exclusive control.

Pine stated that such a union of the Zulus and the Boers, who had wanted to create a settlement in the North-West corner of Zululand, would imperil the safety of Natal.

Sir Henry Barkley exaggerated this failure as a major and decisive defeat of the Boers, and was thereby led to anticipate an immediate application to the High Commissioner to take over the country.

Pelzer wrote: "Although Sekhukhune made overtures for peace, he was not defeated and this fact, together with the shaky financial position, gave Sir Theophilus Shepstone the pretext he required to annex the republic [as the Transvaal, a British colony, on 12 April 1877].

"[15][16] Barkly's warning hastened the action of Lord Carnarvon and led to the dispatch of Sir Theophilus Shepstone, who happened to be in England, on his mission as special commissioner "to carry out any negotiations which may be found necessary and practicable."

In the spring and summer of 1876–77, frontier skirmishes between the Zulus and Boers flared up once again, and Cetewayo, the Zulu king, began moving his impis towards the border between the Transvaal and Zululand.

Believing that the only answer to the instability of the region was British intervention, senior War Office official Sir Garnet Wolseley argued that Britain should "use Cetewayo as a powerful lever to influence wavering spirit".

It has therefore been suggested that the danger that the Zulus presented was specifically manufactured by the British to induce the Boers to accept annexation, and the impis had been massed on the border "on a hint from Shepstone".

Writing on the 14th February 1877, Shepstone asserted: "While I am here, Cetewayo will do nothing; but if I were to withdraw without completing my mission[annexation], I believe that not only the Zulus but every native tribe in the Transvaal and bordering on it would attack and wipe it out."

Thomas Burgers hoped to use the presence of Shepstone to induce the Volksraad to accept, as an alternative to annexation, a reform to the constitution that would strengthen his executive authority and prolong his rule by two more years.

Moreover, due to the economic depression, as well as the "incurable insolvency" of the government, the burghers were ready to support the annexation, which was expected to solve these problems, whilst providing them protection from the natives.

The Boers defeated the British at Laing's Nek and Ingogo, and on 27 February 1881, at Majuba, General Sir George Pomeroy Colley fell at the head of his troops.

[33] Under Law Number 3, all Asians which were defined as "Coolies, Chinese etc, Arabs, Malays, and Mohammedan subjects of the Turkish dominion" were forbidden from owning fixed property, had to register with the local magistrate within 8 days of arriving, were restricted to living in certain neighborhoods and had to pay an entry fee of £25.

[33] Following British diplomatic pressure, Law Number 3 was amended by the volksraad in 1887 to allow the "Asiatics" the right to own fixed property, though not land, and the entry fee was lowered to £3.

[38] The South African historian Ian van der Waag described Boer society as being characterized by a quasi-feudalism as the wealthier families set themselves up as something alike to the marcher lords of medieval Europe.

[43] The field cornets often waged war against local African natives in order to seize land, ivory and people to distribute as spoils to their constituents in exchange for their electoral support, often specifically for elections to higher republic offices.

Rather instead, Mapela led the unsuspecting Boers into an ambush where hundreds of native warriors attacked the Potgieter party, killing Andries, then proceeding to drag Herman up a hill, where he was skinned alive.

[31]: 43 At the same time of these events, the Ndebele chief Magobane (known to the Boers as Makapaan) attacked and killed an entire convoy of women and children traveling to Pretoria.

Commandant-General Stephanus Schoeman did not accept the Volksraad proclamation of 20 September 1858, under which members of the Reformed Churches of South Africa would be entitled to citizenship of the ZAR.

"[56] The proclamation stated that the country was "unstable, ungovernable, bankrupt and facing civil war", though in reality the British wished to annex it for its strategic position, using skirmishes as a casus belli.

The convention was signed in duplicate in London on 27 February 1884, by Hercules Robinson, Paul Kruger, Stephanus Jacobus du Toit and Nicolaas Smit, and later ratified by the South African Republic Volksraad.

Malaboch refused to pay taxes to the Transvaal after it was given back to the Boers in 1881 by the British, which resulted in a military drive against him by the South African Republic (ZAR).

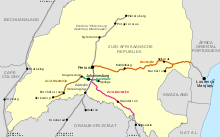

The construction of the Pretoria-Lourenço Marques line allowed the ZAR access to harbour facilities not controlled by the British Empire, a key policy of Paul Kruger who deemed it vital to the country's long-term survival.