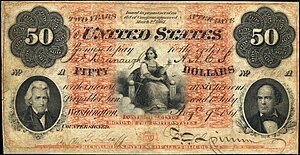

Treasury Note (19th century)

A Treasury Note is a type of short term debt instrument issued by the United States prior to the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

Often they were receivable at face value by the government in payment of taxes and for purchases of publicly owned land,[1] and thus "might to some extent be regarded as paper money.

Characteristically, the issues were not extensive and, as it has been observed, "the polite fiction was always maintained that Treasury Notes did not serve as money when, in fact, to a limited extent they did.

"[3] The value of these notes varied, being worth more or less than par as market conditions fluctuated, and they rapidly disappeared from the financial system after the crisis associated with their issuance had ended.

[4] With the fate of the Continentals in mind, the Founding Fathers embedded in the Constitution no provision for a paper currency, and they forbade the states to make anything but gold or silver a legal tender.

Thus, when the declaration of the War of 1812 impaired the government's ability to raise money via the sale of long-term bonds, the United States had no paper currency nor a central bank with which to obtain emergency short-term financing, and it used its borrowing authority to issue short-term debt in the form of Treasury Notes receivable for public dues or bond purchases.

The first, on June 20, 1812, authorized 1-year Treasury Notes at 5+2⁄5% interest to fill out the unsubscribed portion of an $11 million loan in support of the war with Britain which had just been declared on the 18th.

The Notes were made receivable for all public dues owed the federal government and payable to the order of the owner by endorsement.

The next two acts, those of March 4, 1814 and Dec 26, 1814, called for Note issues both to independently raise revenue as well as to substitute for unsubscribed loans.

During 1814 federal finances deteriorated as the war dragged on, and banks outside New England suspended specie payment on August 31, 1814.

The Act had been drafted during the financial disarray late in the War of 1812 and called for Notes of denomination less than $100 which would bear no interest.

However, when the Jacksonian Democrats rose to power they strongly opposed the bank and began to dismantle its role in federal policy in the mid-1830s.

Particularly controversial was an issue by Secretary Spencer of about $850,000 of Treasury Notes endorsed with a promise for immediate repurchase, principal and interest, by the sub-treasury in New York at par in specie.

Also controversial was the practice by the Secretaries to issue some Notes with only nominal interest, a mere 1/1000 of one percent per annum, to "deposit" in private banks and then draw upon the resulting funds via checks.

[10] Sixty-day and two-year notes were issued, payable to order, receivable in payment of all debts due to the United States, and exchangeable for bonds at par.

Three year Treasury Notes bearing interest at a rate of 7.30% (seven-thirty) were first authorized by the Act of July 17, 1861 to help finance the Civil War.

The Act of March 1, 1862 authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to issue to public creditors certificates of denominations not less than $1,000, signed by the Treasurer, bearing interest at a rate of 6%, and payable in one year or earlier at the option of the government.