Treatment of slaves in the United States

[2][3] African American abolitionist J. Sella Martin countered that apparent "contentment" was a psychological defense to the dehumanizing brutality of having to bear witness to their spouses being sold at auction and their daughters raped.

[7] Sources do identify that black slaves fought for the south, as early as Manassas (battles of Bull Run) and assisted the war effort in many ways.

[11] Compiling a variety of historical sources, historian Kenneth M. Stampp identified in his classic work The Peculiar Institution reoccurring themes in enslavers' efforts to produce the "ideal slave": Enslaved people were punished by whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, mutilation, branding, rape, and imprisonment.

One overseer told a visitor, "Some Negroes are determined never to let a white man whip them and will resist you, when you attempt it; of course you must kill them in that case.

The part held in the hand is nearly an inch in thickness; and, from the extreme end of the butt or handle, the cowskin tapers its whole length to a point.

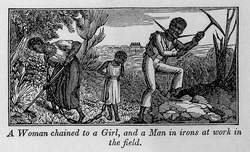

Mutilation of slaves, such as castration of males, removing a front tooth or teeth, and amputation of ears was a relatively common punishment during the colonial era, still used in 1830: it facilitated their identification if they ran away.

Any punishment was permitted for runaway slaves, and many bore wounds from shotgun blasts or dog bites inflicted by their captors.

Myers and Massy describe the practices: "The punishment of deviant slaves was decentralized, based on plantations, and crafted so as not to impede their value as laborers.

A man named Harding describes an incident in which a woman assisted several men in a minor rebellion: "The women he hoisted up by the thumbs, whipp'd and slashed her [sic] with knives before the other slaves till she died.

[23] Wilma Dunaway notes that slaves were often punished for their failure to demonstrate due deference and submission to whites.

[26] Teaching slaves to read was discouraged or (depending upon the state) prohibited, so as to hinder aspirations for escape or rebellion.

[32] This meant that slaves were mainly responsible for their own care, a "health subsystem" that persisted long after slavery was abolished.

[34] Covey suggests that because slaveholders offered poor treatment, slaves relied on African remedies and adapted them to North American plants.

[37] Southern medical schools advertised the ready supply of corpses of the enslaved, for dissection in anatomy classes, as an incentive to enroll.

[38]: 183–184 In the introduction to the oral history project, Remembering Slavery: African Americans Talk About Their Personal Experiences of Slavery and Emancipation, the editors wrote: As masters applied their stamp to the domestic life of the slave quarter, slaves struggled to maintain the integrity of their families.

[39] Elizabeth Keckley, who grew up enslaved in Virginia and later became Mary Todd Lincoln's personal modiste, gave an account of how she had witnessed Little Joe, the son of the cook, being sold to pay his enslaver's bad debt: Joe’s mother was ordered to dress him in his best Sunday clothes and send him to the house, where he was sold, like the hogs, at so much per pound.

When her son started for Petersburgh, ... she pleaded piteously that her boy not be taken from her; but master quieted her by telling that he was going to town with the wagon, and would be back in the morning.

One day she was whipped for grieving for her lost boy.... Burwell never liked to see his slaves wear a sorrowful face, and those who offended in this way were always punished.

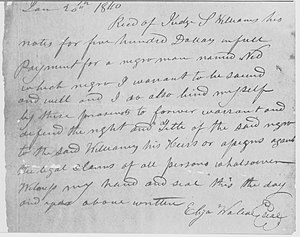

[40]Between 1790 and 1860, about one million enslaved people were forcefully moved from the states on the Atlantic seaboard to the interior in a Second Middle Passage.

Therefore, slavery in the United States encompassed wide-ranging rape and sexual abuse, including many forced pregnancies, in order to produce children for sale.

Foster suggests that men and boys may have also been forced into unwanted sexual activity; one problem in documenting such abuse is that they, of course, did not bear mixed-race children.

The sexual abuse of slaves was partially rooted in historical Southern culture and its view of the enslaved as property.

[55] The evidence of white men raping slave women was obvious in the many mixed-race children who were born into slavery and part of many households.

Jefferson's young concubine, Sally Hemings, was 3/4 white, the daughter of his father-in-law John Wayles, making her the half-sister of his late wife.

[56] By the turn of the 19th century many mixed-race families in Virginia dated to Colonial times; white women (generally indentured servants) had unions with slave and free African-descended men.

Washington became the owner of Martha Custis's slaves under Virginia law when he married her and faced the ethical conundrum of owning his wife's sisters.

[58] Planters with mixed-race children sometimes arranged for their education (occasionally in northern U.S. schools) or apprenticeship in skilled trades and crafts.

When the American Civil War broke out, the majority of the school's 200 students were of mixed race and from wealthy Southern families.

Historian Ty Seidule uses a quote from Frederick Douglass's autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom to describe the experience of the average male slave as being "robbed of wife, of children, of his hard earnings, of home, of friends, of society, of knowledge, and of all that makes his life desirable.

"[60] A quote from a letter by Isabella Gibbons, who had been enslaved by professors at the University of Virginia, is now engraved on the university's Memorial to Enslaved Laborers: Can we forget the crack of the whip, the cowhide, whipping-post, the auction-block, the spaniels, the iron collar, the negro-trader tearing the young child from its mother’s breast as a whelp from the lioness?