Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

[1] With ratification by the U.S. Congress in 1831, the treaty allowed those Choctaw who chose to remain in Mississippi to become the first major non-European ethnic group to gain recognition as U.S. citizens.

On August 25, 1830, the Choctaw were supposed to meet with President Andrew Jackson in Franklin, Tennessee, but Greenwood Leflore informed the Secretary of War, John H. Eaton, that the chiefs were fiercely opposed to attending.

[2] The president was upset but, as the journalist Len Green wrote in 1978, "Although angered by the Choctaw refusal to meet him in Tennessee, Jackson felt from LeFlore's words that he might have a foot in the door and dispatched Secretary of War Eaton and John Coffee to meet with the Choctaws in their nation.

"[3] Jackson appointed Eaton and General John Coffee as commissioners to represent him to meet the Choctaws where the "rabbits gather to dance."

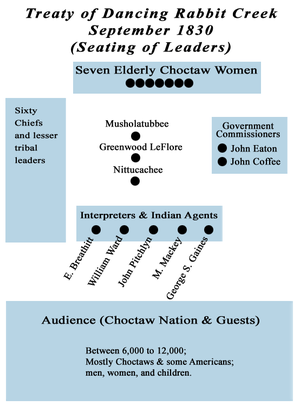

[5] In a carnival-like atmosphere, the US officials explained the policy of removal through interpreters to an audience of 6,000 men, women and children.

[5] The Choctaws faced migration west of the Mississippi River or submitting to U.S. and state law as citizens.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was one of the largest land transfers ever signed between the United States government and American Indians in time of peace.

Each Choctaw head of a family being desirous to remain and become a citizen of the States, shall be permitted to do so, by signifying his intention to the Agent within six months from the ratification of this Treaty, and he or she shall thereupon be entitled to a reservation of one section of six hundred and forty acres of land, to be bounded by sectional lines of survey; in like manner shall be entitled to one half that quantity for each unmarried child which is living with him over ten years of age; and a quarter section to such child as may be under 10 years of age, to adjoin the location of the parent.

If they reside upon said lands intending to become citizens of the States for five years after the ratification of this Treaty, in that case a grant in fee simple shall issue; said reservation shall include the present improvement of the head of the family, or a portion of it.

[7][8] The population transfer occurred in three migrations during the 1831–33 period including the devastating winter blizzard of 1830–31 and the cholera epidemic of 1832.

The Choctaw that migrated, like the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Seminole who followed them, attempted to resurrect their traditional lifestyle and government in their new homeland.

The preamble begins with, A treaty of perpetual, friendship, cession and limits, entered into by John H. Eaton and John Coffee, for and in behalf of the Government of the United States, and the Mingoes, Chiefs, Captains and Warriors of the Choctaw Nation, begun and held at Dancing Rabbit Creek, on the fifteenth of September, in the year eighteen hundred and thirty ...The following terms of the treaty were: 1.

Lands granted to I. Garland, Colonel Robert Cole, Tuppanahomer, John Pytchlynn, Charles Juzan, Johokebetubbe, Eaychahobia, and Ofehoma.

Choctaw Warriors who marched and fought in the army of U.S. General Wayne during the American Revolution and Northwest Indian War will receive an annuity.

[13] The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was ratified by the U.S. Senate on February 25, 1831, and the President was anxious to make it a model of removal.

[13] The chief George W. Harkins wrote a letter to the American people before the removals began: It is with considerable diffidence that I attempt to address the American people, knowing and feeling sensibly my incompetency; and believing that your highly and well improved minds would not be well entertained by the address of a Choctaw.

But having determined to emigrate west of the Mississippi river this fall, I have thought proper in bidding you farewell to make a few remarks expressive of my views, and the feelings that actuate me on the subject of our removal.... We as Choctaws rather chose to suffer and be free, than live under the degrading influence of laws, which our voice could not be heard in their formation.... Much as the state of Mississippi has wronged us, I cannot find in my heart any other sentiment than an ardent wish for her prosperity and happiness.Around 15,000 Choctaws left the old Choctaw Nation for the Indian Territory, much of the state of Oklahoma today.

The Choctaw described their situation in 1849: we have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed, cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged, manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such treatment some of our best men have died.

[1]Joseph B. Cobb, a settler who moved to Mississippi from Georgia, described the Choctaw as having no nobility or virtue at all, and in some respect he found blacks, especially native Africans, more interesting and admirable, the red man's superior in every way.

Their government was dismantled under the Curtis Act, along with those of other Native American nations in the former Indian Territory, to permit the admission of Oklahoma as a state.

Their communal lands were divided and allotted to individual households under the Dawes Act to increase assimilation as American-style farmers.