Treblinka extermination camp

A small number of Jewish men who were not murdered immediately upon arrival became members of its Sonderkommando[15] whose jobs included being forced to bury the victims' bodies in mass graves.

[35] Nazi plans to murder Polish Jews from across the General Government during Aktion Reinhard were overseen in occupied Poland by Odilo Globocnik, a deputy of Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, in Berlin.

[43][44] Before World War II, it was the location of a gravel mining enterprise for the production of concrete, connected to most of the major cities in central Poland by the Małkinia–Sokołów Podlaski railway junction and the Treblinka village station.

[53] To obtain the workforce for Treblinka I, civilians were sent to the camp en masse for real or imagined offences, and sentenced to hard labour by the Gestapo office in Sokołów, which was headed by Gramss.

The quarry, spread over an area of 17 ha (42 acres), supplied road construction material for German military use and was part of the strategic road-building programme in the war with the Soviet Union.

On the other sides, the zone was camouflaged from new arrivals like the rest of the camp, using tree branches woven into barbed wire fences by the Tarnungskommando (the work detail led out to collect them).

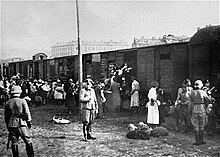

According to German records, including the official report by SS-Brigadeführer Jürgen Stroop, 265,000 Jews were transported in freight trains from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka during the period from 22 July to 12 September 1942.

[75] Treblinka received transports of almost 20,000 foreign Jews between October 1942 and March 1943, including 8,000 from the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia via Theresienstadt, and over 11,000 from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace, Macedonia, and Pirot following an agreement with the Nazi-allied Bulgarian government.

[97] The decoupled locomotive went back to the Treblinka station or to the layover yard in Małkinia for the next load,[92] while the victims were pulled from the carriages onto the platform by Kommando Blau, one of the Jewish work details forced to assist the Germans at the camp.

[88] Between August and September 1942, a large new building with a concrete foundation was built from bricks and mortar under the guidance of Erwin Lambert, who had supervised the construction of gas chambers for the Action T4 involuntary euthanasia program.

[106] The new ones had the highest possible capacity of any gas chambers in the three Reinhard death camps and could murder up to 22,000[115] or 25,000[116] people every day, a fact which Globocnik once boasted about to Kurt Gerstein, a fellow SS officer from Disinfection Services.

[120] According to Jankiel Wiernik, who survived the 1943 prisoner uprising and escaped, when the doors of the gas chambers had been opened, the bodies of the victims were standing and kneeling rather than lying down, due to the severe overcrowding.

[120] The Germans became aware of the political danger associated with the mass burial of corpses in April 1943 after they discovered the graves of Polish victims of the 1940 Katyn massacre carried out by the Soviets near Smolensk.

The Camp 1 Wohnlager residential compound contained barracks for about 700 Sonderkommandos which, when combined with the 300 Totenjuden living across from the gas chambers, brought their grand total to roughly one thousand at a time.

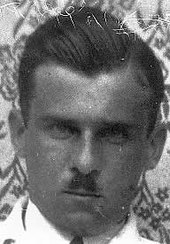

The clandestine unit was first organised by a former Jewish captain of the Polish Army, Dr. Julian Chorążycki, who was described by fellow plotter Samuel Rajzman as noble and essential to the action.

[147] His organising committee included Zelomir Bloch (leadership),[14] Rudolf Masaryk, Marceli Galewski, Samuel Rajzman,[120] Dr. Irena Lewkowska ("Irka",[148] from the sick bay for the Hiwis),[13] Leon Haberman, Chaim Sztajer,[149] Hershl (Henry) Sperling from Częstochowa, and several others.

[68] Of those who broke through, around 70 are known to have survived until the end of the war,[20] including the future authors of published Treblinka memoirs: Richard Glazar, Chil Rajchman, Jankiel Wiernik, and Samuel Willenberg.

The following day, a large group of Jewish Arbeitskommandos who had worked on dismantling the camp structures over the previous few weeks were loaded onto the train and transported, via Siedlce and Chełm, to Sobibór to be gassed on 20 October 1943.

[94] According to the testimony of his colleague Unterscharführer Hans Hingst, Eberl's ego and thirst for power exceeded his ability: "So many transports arrived that the disembarkation and gassing of the people could no longer be handled.

[16] Oskar Berger, a Jewish eyewitness, one of about 100 people who escaped during the 1943 uprising, told of the camp's state when he arrived there in August 1942: When we were unloaded, we noticed a paralysing view – all over the place there were hundreds of human bodies.

[179] According to postwar testimonies, when transports were temporarily halted, then-deputy commandant Kurt Franz wrote lyrics to a song meant to celebrate the Treblinka extermination camp.

[190] The Treblinka I gravel mine functioned at full capacity under the command of Theodor van Eupen until July 1944, with new forced labourers sent to him by Kreishauptmann Ernst Gramss from Sokołów.

[192][43] Strebel, the ethnic German who had been installed in the farmhouse built in place of the camp's original bakery using bricks from the gas chambers, set fire to the building and fled to avoid capture.

[197] When the war ended, destitute and starving locals started walking up the Black Road (as they began to call it) in search of man-made nuggets shaped from melted gold in order to buy bread.

In September 1947, 30 students from the local school, led by their teacher Feliks Szturo and priest Józef Ruciński, collected larger bones and skull fragments into farmers' wicker baskets and buried them in a single mound.

The sculpture represents the trend toward large avant-garde forms introduced in the 1960s throughout Europe, with a granite tower cracked down the middle and capped by a mushroom-like block carved with abstract reliefs and Jewish symbols.

He may not have been aware that the short station platform at Treblinka II greatly reduced the number of wagons that could be unloaded at one time,[205] and may have been adhering to the Soviet trend of exaggerating Nazi crimes for propaganda purposes.

During the 1965 trial of Kurt Franz, the Court of Assize in Düsseldorf concluded that at least 700,000 people were murdered at Treblinka, following a report by Dr. Helmut Krausnick, director of the Institute of Contemporary History.

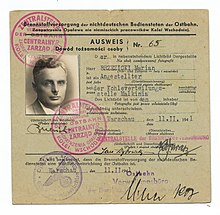

[213] Ząbecki, a Polish member of railway staff before the war, was one of the few non-German witnesses to see most transports that came into the camp; he was present at the Treblinka station when the first Holocaust train arrived from Warsaw.

[246] Treblinka museum receives most visitors per day during the annual March of the Living educational programme which brings young people from around the world to Poland, to explore the remnants of the Holocaust.