Treblinka labor camp

The camp primarily detained men and women accused of economic and criminal offenses, as well as victims of łapankas and raids.

In the interwar period, a gravel pit was established within the triangle marked by the villages of Maliszewa, Poniatowo, and Wólka Okrąglik in Gmina Kosów Lacki in the Sokołów County.

[3] In late 1940/early 1941, due to the infrastructure expansion planned for the invasion of the Soviet Union, the occupying authorities took an interest in the gravel pit.

At the initiative of County Chief Ernst Gramss [pl], a concrete company was established to produce materials from the excavated gravel.

Under German supervision, the prisoners expanded the camp using materials[a] left behind by Wehrmacht units that had been stationed in the county before the invasion of the Soviet Union.

The establishment of the camp was officially sanctioned by an order from Ludwig Fischer, the governor of the Warsaw District, on 15 November 1941 (retroactively effective from 1 September 1941).

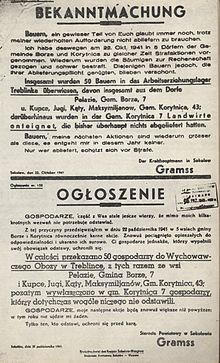

[7] Uniquely, the Polish public was informed about its establishment through posters and the Nazi-controlled Warsaw press shortly after Fischer's order was issued.

In the fall of 1943, additional coils of barbed wire and anti-tank barriers were installed outside the fence, transferred from the liquidated extermination camp Treblinka II.

[13] This part of the camp also had barracks for guards, garages, warehouses, a stable, a pigsty, a henhouse, a bakery, a dairy, a butcher's shop, and a fox farm.

[5][10] Primarily, the camp detained men and women accused of economic and criminal offenses, such as smuggling, black market trading, speculation, failing to meet compulsory agricultural quotas or providing labor, running a business without proper authorization, ignoring a work order, or leaving the workplace without permission.

[22][24] As Władysław Bartoszewski notes, at times, nearly 20% of the inmates were employees of the Warsaw Municipal Administration (e.g., tram operators who didn’t issue tickets to passengers).

Family members of those caught hiding Jews or escaped Soviet prisoners, those arrested for curfew violations, or minor acts of defiance against German authority, and individuals whose judicial proceedings were incomplete or juvenile offenders were also sent there.

[17] In February, a meeting including judicial representatives and the Warsaw Ghetto commissioner Heinz Auerswald decided that juvenile Jews accused of criminal offenses would be sent to Treblinka.

[31] A typical day for a prisoner in the Treblinka labor camp was as follows:[32] Prisoners received official rations: half a liter of watery soup or porridge for breakfast, a liter of soup for lunch, and a cup of unsweetened coffee with between 10 and 20 decagrams of rye bread for dinner, sometimes with a small piece of margarine or marmalade.

[27] Polish prisoners with short sentences worked on a farm half a kilometer away, and Jewish artisans' families were held as hostages.

[29] Other cruel executions occurred at the camp's Holzplatz, where Schwarz and Gruppenwachman Franz Swidersky killed prisoners with hammers or pickaxes.

[55] In late May 1942, German authorities decided to execute Warsaw Ghetto residents sentenced to death by the special court at Treblinka.

A principle of collective responsibility was introduced, meaning that a successful escape would result in the execution of ten or more prisoners employed in the same work detail as the escapee.

However, shortly before the rebellion was to start, the plot was discovered, leading to the arrest and execution of thirteen would-be insurgents, including the alleged leader of the conspiracy, lager-kapo Ignac.

The Germans then separated about 17 skilled workers and began leading the remaining Jews, including women and children, in groups to the Maliszewski Forest, where they were executed beside three previously dug graves.

[68] Between 9 and 10 August 1946, representatives of the Chief Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation inspected the execution site in Maliszewski Forest.

It is known that in September 1947, local children, prompted by their teacher, collected human bones scattered around the camp area and built a mound, which they covered with turf and topped with a cross.

[k][69] It wasn't until 1947, partly due to pressure from Jewish organizations, that the communist authorities took steps to secure the Treblinka camp sites and commemorate the victims.

[69] During the committee's first meeting on 25 July 1947, they decided to hold a closed competition for the design of a mausoleum and organize a fundraising campaign to finance its construction.

[78] Its implementation was significantly delayed, primarily due to lack of funds, the need to expropriate nearly 127 ha of land, and difficulties finalizing the detailed project plans.

[79] It wasn't until 1961 that a final decision was made to build the monument-mausoleum, with the task assigned to the Artistic and Research Workshops at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts.

Franciszek Strynkiewicz, representing the workshops, joined Haupt and Duszeńko, contributing the artistic element of the labor camp victims' monument.

[93] The central element of the commemoration is the Stations of the Cross, starting at the former gravel pit and ending with a mass at the execution site monument.

[102] The camp commandant, Theodor van Eupen, was likely killed by a Soviet partisan unit Vanguard led by Wasilij Tichonin [pl][103] in an ambush near the village of Lipówka on 11 December 1944.

Some sources indicate that the information about the commandant's death in this skirmish is not unequivocally confirmed,[14] but others suggest that van Eupen's identity was established based on documents found on his body.