Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire

At approximately 4:40 pm on Saturday, March 25, 1911, as the workday was ending, a fire flared up in a scrap bin under one of the cutter's tables at the northeast corner of the 8th floor.

The scraps piled up from the last time the bin was emptied, coupled with the hanging fabrics that surrounded it; the steel trim was the only thing that was not highly flammable.

A series of articles in Collier's noted a pattern of arson among certain sectors of the garment industry whenever their particular product fell out of fashion or had excess inventory in order to collect insurance.

Some victims pried the elevator doors open and jumped into the empty shaft, trying to slide down the cables or to land on top of the car.

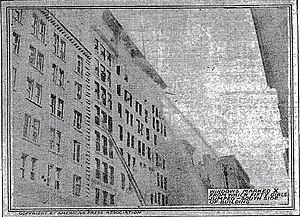

[30] A large crowd of bystanders gathered on the street, witnessing 62 people jumping or falling to their deaths from the burning building.

It was a raw, unpleasant day and the comfortable reading room seemed a delightful place to spend the remaining few hours until the library closed.

Word had spread through the East Side, by some magic of terror, that the plant of the Triangle Waist Company was on fire and that several hundred workers were trapped.

Occasionally a girl who had hesitated too long was licked by pursuing flames and, screaming with clothing and hair ablaze, plunged like a living torch to the street.

[43] Bodies of victims were taken to Charities Pier (also called Misery Lane), located at 26th Street and the East River, for identification by friends and relatives.

[35] Twenty-two victims of the fire were buried by the Hebrew Free Burial Association[45] in a special section at Mount Richmond Cemetery.

[46] Six victims remained unidentified until 2011, when Michael Hirsch, a historian, completed four years of researching newspaper articles and other sources for missing persons and was able to identify each of them by name.

Originally interred elsewhere on the grounds, their remains now lie beneath a monument to the tragedy, a large marble slab featuring a kneeling woman.

[50] Max Steuer, counsel for the defendants, managed to destroy the credibility of one of the survivors, Kate Alterman, by asking her to repeat her testimony a number of times, which she did without altering key phrases.

[52] The jury acquitted the two men of first- and second-degree manslaughter, but they were found liable of wrongful death during a subsequent civil suit in 1913 in which plaintiffs were awarded compensation in the amount of $75 per deceased victim.

She used the fire as an argument for factory workers to organize:[57] I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship.

We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting... We have tried you citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers, brothers, and sisters by way of a charity gift.

But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions which are unbearable, the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

The committee's representatives in Albany obtained the backing of Tammany Hall's Al Smith, the Majority Leader of the Assembly, and Robert F. Wagner, the Majority Leader of the Senate, and this collaboration of machine politicians and reformers—also known as "do-gooders" or "goo-goos"—got results, especially since Tammany's chief, Charles F. Murphy, realized the goodwill to be had as champion of the downtrodden.

"[65][66] New laws mandated better building access and egress, fireproofing requirements, the availability of fire extinguishers, the installation of alarm systems and automatic sprinklers, and better eating and toilet facilities for workers, and limited the number of hours that women and children could work.

[71] The last living survivor of the fire was Rose Freedman, née Rosenfeld, who died in Beverly Hills, California, on February 15, 2001, at the age of 107.

Senator Elizabeth Warren delivered a speech in Washington Square Park supporting her presidential campaign, a few blocks from the location of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

[80] The Coalition grew out of a public art project called Chalk, created by New York City filmmaker Ruth Sergel.

[81] Every year beginning in 2004, Sergel and volunteer artists went across New York City on the anniversary of the fire to inscribe in chalk the names, ages, and causes of death of the victims in front of their former homes, often including drawings of flowers, tombstones, or a triangle.

[77][82] From July 2009 to the weeks leading up to the 100th anniversary, the Coalition served as a clearinghouse to organize some 200 activities as varied as academic conferences, films, theater performances, art shows, concerts, readings, awareness campaigns, walking tours, and parades that were held in and around New York City and in other cities across the nation, including San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Minneapolis, Boston, and Washington, D.C.[77] The ceremony, which was held in front of the building where the fire took place, was preceded by a march through Greenwich Village by thousands of people, some carrying shirtwaists—women's blouses—on poles, with sashes commemorating the names of those who died in the fire.

Senator Charles Schumer, New York City Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, the actor Danny Glover, and Suzanne Pred Bass, the grandniece of Rosie Weiner, a young woman killed in the blaze.

[83][84] At 4:45 pm EST, the moment the first fire alarm was sounded in 1911, hundreds of bells rang out in cities and towns across the nation.

[86] On December 22, 2015, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced that $1.5 million from state economic development funds would be earmarked to build the Triangle Fire Memorial.

Films and television Music Theatre and dance Literature Notes Bibliography Further reading General Contemporaneous accounts Trial Articles Memorials and centennial