Triangular number

It represents the number of distinct pairs that can be selected from n + 1 objects, and it is read aloud as "n plus one choose two".

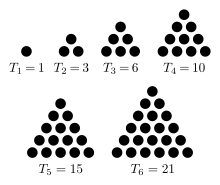

, imagine a "half-rectangle" arrangement of objects corresponding to the triangular number, as in the figure below.

Copying this arrangement and rotating it to create a rectangular figure doubles the number of objects, producing a rectangle with dimensions

The German mathematician and scientist, Carl Friedrich Gauss, is said to have found this relationship in his early youth, by multiplying n/2 pairs of numbers in the sum by the values of each pair n + 1.

[3] However, regardless of the truth of this story, Gauss was not the first to discover this formula, and some find it likely that its origin goes back to the Pythagoreans in the 5th century BC.

[4] The two formulas were described by the Irish monk Dicuil in about 816 in his Computus.

[6] Occasionally it is necessary to compute large triangular numbers where the standard formula t = n*(n+1)/2 would suffer integer overflow before the final division by 2.

If n is odd, the binary OR operation n|1 has no effect, so this is equivalent to t = n * ((n+1)/2) and thus correct.

This property, colloquially known as the theorem of Theon of Smyrna,[9] is visually demonstrated in the following sum, which represents

This fact can also be demonstrated graphically by positioning the triangles in opposite directions to create a square: The double of a triangular number, as in the visual proof from the above section § Formula, is called a pronic number.

Also, the square of the nth triangular number is the same as the sum of the cubes of the integers 1 to n. This can also be expressed as

Triangular numbers correspond to the first-degree case of Faulhaber's formula.

In base 10, the digital root of a nonzero triangular number is always 1, 3, 6, or 9.

Hence, every triangular number is either divisible by three or has a remainder of 1 when divided by 9: The digital root pattern for triangular numbers, repeating every nine terms, as shown above, is "1, 3, 6, 1, 6, 3, 1, 9, 9".

For example, the digital root of 12, which is not a triangular number, is 3 and divisible by three.

Note that b will always be a triangular number, because 8Tn + 1 = (2n + 1)2, which yields all the odd squares are revealed by multiplying a triangular number by 8 and adding 1, and the process for b given a is an odd square is the inverse of this operation.

In addition, the nth partial sum of this series can be written as 2n/n + 1 Two other formulas regarding triangular numbers are

both of which can easily be established either by looking at dot patterns (see above) or with some simple algebra.

In 1796, Gauss discovered that every positive integer is representable as a sum of three triangular numbers, writing in his diary his famous words, "ΕΥΡΗΚΑ!

The three triangular numbers are not necessarily distinct, or nonzero; for example 20 = 10 + 10 + 0.

This is a special case of the Fermat polygonal number theorem.

Wacław Franciszek Sierpiński posed the question as to the existence of four distinct triangular numbers in geometric progression.

It was conjectured by Polish mathematician Kazimierz Szymiczek to be impossible and was later proven by Fang and Chen in 2007.

[11][12] Formulas involving expressing an integer as the sum of triangular numbers are connected to theta functions, in particular the Ramanujan theta function.

[13][14] The number of line segments between closest pairs of dots in the triangle can be represented in terms of the number of dots or with a recurrence relation:

In the limit, the ratio between the two numbers, dots and line segments is

The triangular number Tn solves the handshake problem of counting the number of handshakes if each person in a room with n + 1 people shakes hands once with each person.

Under this method, an item with a usable life of n = 4 years would lose 4/10 of its "losable" value in the first year, 3/10 in the second, 2/10 in the third, and 1/10 in the fourth, accumulating a total depreciation of 10/10 (the whole) of the losable value.

Board game designers Geoffrey Engelstein and Isaac Shalev describe triangular numbers as having achieved "nearly the status of a mantra or koan among game designers", describing them as "deeply intuitive" and "featured in an enormous number of games, [proving] incredibly versatile at providing escalating rewards for larger sets without overly incentivizing specialization to the exclusion of all other strategies".

for the sum whose terms are the integers from 1 to n (the nth triangular number).