Tribes of Montenegro

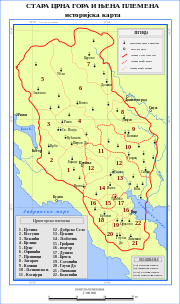

However, in anthropological and historical studies, the tribes are divided into those of Old Montenegro, Brda, Old Herzegovina and Primorje, then into sub-groups (bratstva i.e. “brotherhoods” or “clans”) and finally into families.

Today they are mainly studied within the frameworks of social anthropology and family history, as they have not been used in official structures since the time of the Principality of Montenegro, although some tribal regions overlap with contemporary municipal areas.

[1][2] This theory suggests that the origins of the tribes in Montenegro, as well as those of Herzegovina and Northern Albania, date back well before the establishment of the medieval South Slavic states.

[9] After the Ottoman conquest, the medieval župas, heart of the territorial organization of the feudal Nemanjić state and its successors, were replaced with administrative units called nahiyas.

The American anthropologist Christopher Boehm, who had studied them extensively, believed that only a few of them are descended from the ancient pre-Slavic population of the Western Balkans, namely the Illyrians.

[25] Djilas in his boyhood memoirs described the blood feuds and resulting vengeance as "was the debt we paid for the love and sacrifice our forebears and fellow clansmen bore for us.

It was centuries of manly pride and heroism, survival, a mother's milk and a sister's vow, bereaved parents and children in black, joy, and songs turned into silence and wailing.

This historical process laid foundation for the creation of modern Montenegro, which evolved to the country from a loose federation of the tribes in the 18/19th turn of the century.

Morača is a particular example since it served as a gathering place of both Rovčani and Moračani tribe and, up to the beginning of the 19th century, Vasojevići, who later developed their own cult after Đurđevi Stupovi.

As far as historical records by age and testimony go, it is shown that at least between 14th and 15th century many tribal migrations to Montenegro from Kosovo, Metohija, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina took place.

[33] In 1697, with the election of the Danilo I Šćepčević from the Njeguši tribe as the metropolitan (vladika) of Cetinje, succession became restricted to the Petrović clan until 1918 (with exception of short periods of rule by Šćepan Mali and Arsenije Plamenac).

[17] Despite several attempts by the vladikas to end it, tribes continued the tradition of feuding and remained divided, resulting in a weak central government that had the effect of making Montenegro backward and also vulnerable against the Ottomans.

A mysterious man of unknown origin, he pretented to be the defunct Russian emperor Peter III and managed to get himself elected as the leader of Montenegro by the assembly of tribal chefs (Serbian: zbor), in 1767.

[35] The news of Šćepan's election was enthusiastically received by the Brda tribes and, more generally, all the tribesmen had such faith in their new leader that Venice failed to shake his rule.

[36] Relying on his charismatic qualities, Šćepan was the first to give Montenegro a form of central authority, managing to suppress the blood feud which had ravaged the tribes and instigating a system of justice in its place.

[38] However, Šćepan Mali was murdered in August 1773[38] and a year later, in the same month,[39] Mehmed Pasha Bushati attacked the Kuči and Bjelopavlići,[40] but was decisively defeated with the help of the Montenegrins, after which the vizier and his Albanian troops withdrew to Scutari.

[38] Petar I came to power in 1784 and, after several appeals (Serbian: poslanice) to the tribal chiefs, managed to successfully unite the tribes of Old Montenegro against the Ottomans at the Assembly of Cetinje, in 1787.

[42] In 1789, Jovan Radonjić, the governor of Montenegro, wrote for the second time to the Russian empress, Catherine II: Now, all of us Serbs from Montenegro, Herzegovina, Banjani, Drobnjaci, Kuči, Piperi, Bjelopavlići, Zeta, Klimenti, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Peć, Kosovo, Prizren, Arbania, Macedonia belong to your Excellency and pray that you, as our kind mother, send over Prince Sofronije Jugović-Marković.

[43] In the following years, Catherine and the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II offered financial support, military advisors and volunteers to bolster the Montenegrin war effort against the Ottomans.

[44][45] This act was adopted on the eve of the battle of Krusi, on 4 October 1796, where the Montenegrins defeated the Ottoman army of Kara Mahmud Pasha, who was killed during the confrontation.

[49] He waged a successful campaign against the bey of Bosnia in 1819; the repulse of an Ottoman invasion from Albania during the Russo-Turkish War led to the recognition of Montenegrin sovereignty over Piperi.

[50] A civil war broke out in 1847, in which the Piperi and Crmnica sought to secede from the principality which was afflicted by a famine, and could not relieve them with the rations of the Ottomans, the secessionists were subdued and their ringleaders shot.

[52] A conspiracy was formed against Danilo, led by his uncles George and Pero, the situation came to its height when the Ottomans stationed troops along the Herzegovinian frontier, provoking the mountaineers.

[52] Some urged an attack on Bar, others raided into Herzegovina, and the discontent of Danilo's subjects grew so much that the Piperi, Kuči and Bjelopavlići, the recent and still unamalgamated acquisitions, proclaimed themselves an independent state in July, 1854.

[53] Croatian historian Ivo Banac claims that with Serbian Orthodox religious and cultural influence, Montenegrins had lost sight of their complex origin and thought of themselves as Serbs.

During World War II, the tribes were internally mainly divided between the two sides of Chetniks (Serbian royalists) and Yugoslav Partisans (communists), that were fighting each other for the rule of Yugoslavia.

[58] Serbian ethnologist Jovan Cvijić (1922) noted the Slavic assimilation and migration of many Albanian groups of Mataruge, Macure, Mugoši, Kriči, Španji, Ćići and other Albanians/Vlachs who were mentioned as brotherhoods or tribes.

[61] The Serbian anthropologist Petar Vlahović argued that the Slavs that had settled by the 7th century came into contact with the remnants of Romans (Vlachs), who later became a component part of all the Balkan peoples.

The latter were concentrated in the northeast of Zeta river, and predominantly consisted of tribes who fled Ottoman occupation, and got incorporated into Montenegro following the battles at Martinići and Krusi (1796).

[17] There are also large dispersed or emigrant brotherhoods, such as Maleševci, Pavkovići, Prijedojevići, Trebješani (Nikšići), Miloradovići-Hrabreni, Ugrenovići, Bobani, Pilatovci, Mrđenovići and Veljovići.