Trireme

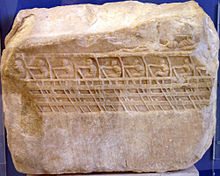

Fragments from an 8th-century relief at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh depicting the fleets of Tyre and Sidon show ships with rams, and fitted with oars pivoted at two levels.

[9] Modern scholarship is divided on the provenance of the trireme, Greece or Phoenicia, and the exact time it developed into the foremost ancient fighting ship.

[citation needed] Herodotus mentions that the Egyptian pharaoh Necho II (610–595 BC) built triremes on the Nile, for service in the Mediterranean, and in the Red Sea, but this reference is disputed by modern historians, and attributed to a confusion, since "triērēs" was by the 5th century used in the generic sense of "warship", regardless its type.

[17] Thucydides clearly states that in the time of the Persian Wars, the majority of the Greek navies consisted of (probably two-tiered) penteconters and ploia makrá ("long ships").

After Salamis and another Greek victory over the Persian fleet at Mycale, the Ionian cities were freed, and the Delian League was formed under the aegis of Athens.

In addition, as it provided permanent employment for the city's poorer citizens, the fleet played an important role in maintaining and promoting the radical Athenian form of democracy.

There would be three files of oarsmen on each side tightly but workably packed by placing each man outboard of, and in height overlapping, the one below, provided that thalamian tholes were set inboard and their ports enlarged to allow oar movement.

If the center of gravity were placed any higher, the additional beams needed to restore stability would have resulted in the exclusion of the Thalamian the holes due to the reduced hull space.

[4] Triremes required a great deal of upkeep in order to stay afloat, as references to the replacement of ropes, sails, rudders, oars and masts in the middle of campaigns suggest.

Additionally, hull plank butts would remain in compression in all but the most severe sea conditions, reducing working of joints and consequent leakage.

Making durable rope consisted of using both papyrus and white flax; the idea to use such materials is suggested by evidence to have originated in Egypt.

[3] The use of light woods meant that the ship could be carried ashore by as few as 140 men,[21] but also that the hull soaked up water, which adversely affected its speed and maneuverability.

There were rare instances, however, when experienced crews and new ships were able to cover nearly twice that distance (Thucydides mentions a trireme travelling 300 kilometres in one day).

[37][38] These were divided into the 170 rowers (eretai), who provided the ship's motive power, the deck crew headed by the trierarch and a marine detachment.

Victor Davis Hanson argues that this "served the larger civic interest of acculturating thousands as they worked together in cramped conditions and under dire circumstances.

Cities visited, which suddenly found themselves needing to provide for large numbers of sailors, usually did not mind the extra business, though those in charge of the fleet had to be careful not to deplete them of resources.

[50] In the Athenian navy, the crews enjoyed long practice in peacetime, becoming skilled professionals and ensuring Athens' supremacy in naval warfare.

In the sea trials of the reconstruction Olympias, it was evident that this was a difficult problem to solve, given the amount of noise that a full rowing crew generated.

In Aristophanes' play The Frogs two different rowing chants can be found: "ryppapai" and "o opop", both corresponding quite well to the sound and motion of the oar going through its full cycle.

Whereas the Athenians relied on speed and maneuverability, where their highly trained crews had the advantage, other states favored boarding, in a situation that closely mirrored the one that developed during the First Punic War.

[58] As the presence of too many heavily armed hoplites on deck tended to destabilize the ship, the epibatai were normally seated, only rising to carry out any boarding action.

Artillery in the form of ballistas and catapults was widespread, especially in later centuries, but its inherent technical limitations meant that it could not play a decisive role in combat.

The preferred method of attack was to come in from astern, with the aim not of creating a single hole, but of rupturing as big a length of the enemy vessel as possible.

It has also been recorded that if a battle were to take place in the calmer water of a harbor, oarsmen would join the offensive and throw stones (from a stockpile aboard) to aid the marines in harassing/attacking other ships.

The Spartan General Brasidas summed up the difference in approach to naval warfare between the Spartans and the Athenians: "Athenians relied on speed and maneuverability on the open seas to ram at will clumsier ships; in contrast, a Peloponnesian armada might win only when it fought near land in calm and confined waters, had the greater number of ships in a local theater, and if its better-trained marines on deck and hoplites on shore could turn a sea battle into a contest of infantry.

Inclement weather would greatly decrease the crew's odds of survival, leading to a situation like that off Cape Athos in 411 (12 of 10,000 men were saved).

In the Peloponnesian War, after the Battle of Arginusae, six Athenian generals were executed for failing to rescue several hundred of their men clinging to wreckage in the water.

"[65] The image found on an early-5th-century black-figure, depicting prisoners bound and thrown into the sea being pushed and prodded under water with poles and spears, shows that enemy treatment of captured sailors in the Peloponnesian War was often brutal.

By Imperial times, Rome controlled the entirety of the Mediterranean and thus the need to maintain a powerful navy was minimal, as the only enemy they would be facing is pirates.

As a result, the fleet was relatively small and had mostly political influence, controlling the grain supply and fighting pirates, who usually employed light biremes and liburnians.