Tunguska event

[1][3] The explosion over the sparsely populated East Siberian taiga felled an estimated 80 million trees over an area of 2,150 km2 (830 sq mi) of forest, and eyewitness accounts suggest up to three people may have died.

before the implementation of the Soviet calendar in 1918), at around 7:17 am local time, Evenki natives and Russian settlers in the hills northwest of Lake Baikal observed a bluish light, nearly as bright as the Sun, moving across the sky and leaving a thin trail.

[11] It has been theorized that this sustained glowing effect was due to light passing through high-altitude ice particles that had formed at extremely low temperatures as a result of the explosion – a phenomenon that decades later was reproduced by Space Shuttles.

The testimony of S. Semenov, as recorded by Russian mineralogist Leonid Kulik's expedition in 1930:[17] At breakfast time I was sitting by the house at Vanavara Trading Post [approximately 65 kilometres (40 mi) south of the explosion], facing north.

[...] I suddenly saw that directly to the north, over Onkoul's Tunguska Road, the sky split in two and fire appeared high and wide over the forest [as Semenov showed, about 50 degrees up – expedition note].

Later we saw that many windows were shattered, and in the barn, a part of the iron lock snapped.Testimony of Chuchan of the Shanyagir tribe, as recorded by I. M. Suslov in 1926:[18] We had a hut by the river with my brother Chekaren.

The author of these lines was meantime in the forest about 6 versts [6.4 km] north of Kirensk and heard to the north-east some kind of artillery barrage, that repeated at intervals of 15 minutes at least 10 times.

Upon closer inspection to the north, i.e. where most of the thumps were heard, a kind of an ashen cloud was seen near the horizon, which kept getting smaller and more transparent and possibly by around 2–3 p.m. completely disappeared.Since the 1908 event, an estimated 1,000 scholarly papers (most in Russian) have been published about the Tunguska explosion.

Only more than a decade after the event did any scientific analysis of the region take place, in part due to the area's isolation and significant political upheaval affecting Russia in the 1910s.

In 1921, the Russian mineralogist Leonid Kulik led a team to the Podkamennaya Tunguska River basin to conduct a survey for the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

In 1938, Kulik arranged for an aerial photographic survey of the area[27] covering the central part of the leveled forest (250 square kilometres [97 sq mi]).

Chemical analysis showed that the spheres contained high proportions of nickel relative to iron, which is also found in meteorites, leading to the conclusion they were of extraterrestrial origin.

[35] In 2013, a team of researchers published the results of an analysis of micro-samples from a peat bog near the centre of the affected area, which show fragments that may be of extraterrestrial origin.

The heat generated by compression of air in front of the body (ram pressure) as it travels through the atmosphere is immense and most meteoroids burn up or explode before they reach the ground.

[41] Since the second half of the 20th century, close monitoring of Earth's atmosphere through infrasound and satellite observation has shown that asteroid air bursts with energies comparable to those of nuclear weapons routinely occur, although Tunguska-sized events, on the order of 5–15 megatons,[42] are much rarer.

[44] Most of these are thought to be caused by asteroid impactors, as opposed to mechanically weaker cometary materials, based on their typical penetration depths into the Earth's atmosphere.

[42] In 2020, a group of Russian scientists used a range of computer models to calculate the passage of asteroids with diameters of 200, 100, and 50 metres at oblique angles across Earth's atmosphere.

The model that most closely matched the observed event was an iron asteroid up to 200 metres in diameter, travelling at 11.2 km per second, that glanced off the Earth's atmosphere and returned into solar orbit.

A comet is composed of dust and volatiles, such as water ice and frozen gases, and could have been completely vaporised by the impact with Earth's atmosphere, leaving no obvious traces.

This hypothesis was further boosted in 2001, when Farinella, Foschini, et al. released a study calculating the probabilities based on orbital modelling extracted from the atmospheric trajectories of the Tunguska object.

[55] During the 1990s, Italian researchers, coordinated by the physicist Giuseppe Longo from the University of Bologna, extracted resin from the core of the trees in the area of impact to examine trapped particles that were present during the 1908 event.

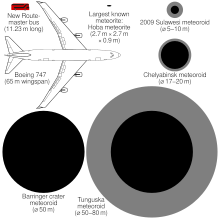

Researchers used data from both Tunguska and Chelyabinsk to perform a statistical study of over 50 million combinations of bolide and entry properties that could produce Tunguska-scale damage when breaking apart or exploding at similar altitudes.

Some models focused on combinations of properties which created scenarios with similar effects to the tree-fall pattern as well as the atmospheric and seismic pressure waves of Tunguska.

Four different computer models produced similar results; they concluded that the likeliest candidate for the Tunguska impactor was a stony body between 50 and 80 m (164 and 262 ft) in diameter, entering the atmosphere at roughly 55,000 km/h (34,000 mph), exploding at 10 to 14 km (6 to 9 mi) altitude, and releasing explosive energy equivalent to between 10 and 30 megatons.

[67] The main points of the study are that: Cheko, a small lake located in Siberia close to the epicentre of the 1908 Tunguska explosion, might fill a crater left by the impact of a fragment of a cosmic body.

The upper 100‐cm long section, in addition to pollen of taiga forest trees such as Abies, Betula, Juniperus, Larix, Pinus, Picea, and Populus, contains abundant remains of hydrophytes, i.e., aquatic plants probably deposited under lacustrine conditions similar to those prevailing today.

The Russian scientists in 2017 counted at least 280 such annual varves in the 1260 mm long core sample pulled from the bottom of the lake, representing an age older than the Tunguska event.

Astrophysicist Wolfgang Kundt has proposed that the Tunguska event was caused by the release and subsequent explosion of 10 million tons of natural gas from within the Earth's crust.

[72][73][74][75][76] The basic idea is that natural gas leaked out of the crust and then rose to its equal-density height in the atmosphere; from there, it drifted downwind, in a sort of wick, which eventually found an ignition source such as lightning.

[83][84][85] The notion that it was caused by an alien spaceship is a popular one that gained prominence following the publication of Russian science fiction writer Alexander Kazantsev's 1946 short story "Explosion".