Tunicate

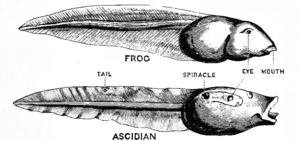

Both groups are chordates, as evidenced by the fact that during their mobile larval stage, tunicates possess a notochord, a hollow dorsal nerve cord, pharyngeal slits, post-anal tail, and an endostyle.

Some are supported by a stalk, but most are attached directly to a substrate, which may be a rock, shell, coral, seaweed, mangrove root, dock, piling, or ship's hull.

[13] No doubt largely because of his influence, various authors supported the term, either as such, or as the slightly older "Urochordata", but this usage is invalid because "Tunicata" has precedence, and grounds for superseding the name never existed.

[18] Tunicates are more closely related to craniates (including hagfish, lampreys, and jawed vertebrates) than to lancelets, echinoderms, hemichordates, Xenoturbella or other invertebrates.

[22] The Tunicata contain roughly 3,051 described species,[12] traditionally divided into these classes: Members of the Sorberacea were included in Ascidiacea in 2011 as a result of rDNA sequencing studies.

[27][25][28] Oikopleuridae Kowalevskiidae Fritillariidae Pyrosomida Salpida Doliolida Phlebobranchia Aplousobranchia Molgulidae Styelidae Pyuridae Undisputed fossils of tunicates are rare.

The best known and earliest unequivocally identified species is Shankouclava shankouense from the Lower Cambrian Maotianshan Shale at Shankou village, Anning, near Kunming (South China).

[30] A well-preserved Cambrian fossil, Megasiphon thylakos, shows that the tunicate basic body design had already been established 500 million years ago.

[31] Three enigmatic species were also found from the Ediacaran period – Ausia fenestrata from the Nama Group of Namibia, the sac-like Yarnemia ascidiformis, and one from a second new Ausia-like genus from the Onega Peninsula of northern Russia, Burykhia hunti.

[32][33] Ausia and Burykhia lived in shallow coastal waters slightly more than 555 to 548 million years ago, and are believed to be the oldest evidence of the chordate lineage of metazoans.

[35][36] A multi-taxon molecular study in 2010 proposed that sea squirts are descended from a hybrid between a chordate and a protostome ancestor (before the divergence of panarthropods and nematodes).

In the simplest systems, the individual animals are widely separated, but linked together by horizontal connections called stolons, which grow along the seabed.

Inside the tunic is the body wall or mantle composed of connective tissue, muscle fibres, blood vessels, and nerves.

It has a ciliated groove known as an endostyle on its ventral surface, and this secretes a mucous net which collects food particles and is wound up on the dorsal side of the pharynx.

Except for the heart, gonads, and pharynx (or branchial sac), the organs are enclosed in a membrane called an epicardium, which is surrounded by the jelly-like mesenchyme.

Ascidian tunicates begin life as a lecithotrophic (non-feeding) mobile larva that resembles a tadpole,[39] with the exception of some members of the families Styelidae and Molgulidae which has direct development.

In some species of Ascidiidae and Perophoridae, it contains high concentrations of the transitional metal vanadium and vanadium-associated proteins in vacuoles in blood cells known as vanadocytes.

[49][50][51] Nearly all adult tunicates are suspension feeders (the larval form usually does not feed), capturing planktonic particles by filtering sea water through their bodies.

The net is made of sticky mucus threads with holes about 0.5 μm in diameter which can trap planktonic particles including bacteria.

After digestion, the food is moved on through the intestine, where absorption takes place, and the rectum, where undigested remains are formed into faecal pellets or strings.

A few deepwater species, such as Megalodicopia hians, are sit-and-wait predators, trapping tiny crustacea, nematodes, and other small invertebrates with the muscular lobes which surround their buccal siphons.

Many physical changes occur to the tunicate's body during metamorphosis, one of the most significant being the reduction of the cerebral ganglion, which controls movement and is the equivalent of the vertebrate brain.

In the solitary life history phase, an oozoid reproduces asexually, producing a chain of tens or hundreds of individual zooids by budding along the length of a stolon.

[58] Self-incompatibility promotes out-crossing, and thus provides the adaptive advantage at each generation of the masking of deleterious recessive mutations (i.e. genetic complementation)[59] and the avoidance of inbreeding depression.

These findings suggest that self-fertilization gives rise to inbreeding depression associated with developmental deficits that are likely caused by expression of deleterious recessive mutations.

[61] O. dioica can be maintained in laboratory culture, and is of growing interest as a model organism because of its phylogenetic position within the closest sister group to vertebrates.

The carpet tunicate (Didemnum vexillum) has taken over a 6.5 sq mi (17 km2) area of the seabed on the Georges Bank off the northeast coast of North America, covering stones, molluscs, and other stationary objects in a dense mat.

[62] D. vexillum, Styela clava and Ciona savignyi have appeared and are thriving in Puget Sound and Hood Canal in the Pacific Northwest.

The mechanisms underlying the phenomenon may lead to insights about the potential of cells and tissues to be reprogrammed and to regenerate compromised human organs.

The nuclear genome of the appendicularian Oikopleura dioica appears to be one of the smallest among metazoans[75] and this species has been used to study gene regulation and the evolution and development of chordates.