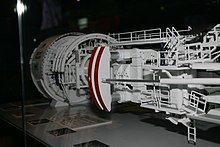

Tunnel boring machine

Tunnels are excavated through hard rock, wet or dry soil, or sand, each of which requires specialized technology.

Narrower tunnels are typically bored using trenchless construction methods or horizontal directional drilling rather than TBMs.

However, this was only the invention of the shield concept and did not involve the construction of a complete tunnel boring machine, the digging still having to be accomplished by the then standard excavation methods.

[9][10][11][12][13] Commissioned by the King of Sardinia in 1845 to dig the Fréjus Rail Tunnel between France and Italy through the Alps, Maus had it built in 1846 in an arms factory near Turin.

It consisted of more than 100 percussion drills mounted in the front of a locomotive-sized machine, mechanically power-driven from the entrance of the tunnel.

The Revolutions of 1848 affected the funding, and the tunnel was not completed until 10 years later, by using less innovative and less expensive methods such as pneumatic drills.

[14] In the United States, the first boring machine to have been built was used in 1853 during the construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in northwest Massachusetts.

[21] In the 1870s, John D. Brunton of England built a machine employing cutting discs that were mounted eccentrically on rotating plates, which in turn were mounted eccentrically on a rotating plate, so that the cutting discs would travel over almost all of the rock face that was to be removed.

[22][23] The first TBM that tunneled a substantial distance was invented in 1863 and improved in 1875 by British Army officer Major Frederick Edward Blackett Beaumont (1833–1895); Beaumont's machine was further improved in 1880 by British Army officer Major Thomas English (1843–1935).

[32][33][7] During the late 19th and early 20th century, inventors continued to design, build, and test TBMs for tunnels for railroads, subways, sewers, water supplies, etc.

[39] A TBM with a bore diameter of 14.4 m (47 ft 3 in) was manufactured by The Robbins Company for Canada's Niagara Tunnel Project.

An earth pressure balance TBM known as Bertha with a bore diameter of 17.45 meters (57.3 ft) was produced by Hitachi Zosen Corporation in 2013.

Two TBMs supplied by CREG excavated two tunnels for Kuala Lumpur's Rapid Transit with a boring diameter of 6.67 m (21.9 ft).

The same company built the world's largest-diameter slurry TBM, excavation diameter of 17.6 meters (58 ft), owned and operated by the French construction company Dragages Hong Kong (Bouygues' subsidiary) for the Tuen Mun Chek Lap Kok link in Hong Kong.

The stability of the walls also influences the method by which the TBM anchors itself in place so that it can apply force to the cutting head.

At the end of a Wirth boring cycle, legs drop to the ground, the grippers are retracted, and the machine advances.

The gripper shield anchors the TBM so that pressure can be applied to the cutter head while simultaneously the concrete lining is being constructed.

Such additives can separately be injected in the cutter head and extraction screw to ensure that the muck is sufficiently cohesive to maintain pressure and restrict water flow.

EPB has allowed soft, wet, or unstable ground to be tunneled with a speed and safety not previously possible.

The cutter head is filled with pressurised slurry, typically made of bentonite clay that applies hydrostatic pressure to the face.

A caisson system is sometimes placed at the cutting head to allow workers to operate the machine,[47][48] although air pressure may reach elevated levels in the caisson, requiring workers to be medically cleared as "fit to dive" and able to operate pressure locks.

Urban tunnelling has the special requirement that the surface remain undisturbed, and that ground subsidence be avoided.

TBMs with positive face control, such as earth pressure balance (EPB) and slurry shield (SS), are used in such situations.

Both types (EPB and SS) are capable of reducing the risk of surface subsidence and voids if ground conditions are well documented.