Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

From 1976 to 1979, an estimated 20,000 people were imprisoned at Tuol Sleng and it was one of between 150 and 196 torture and execution centers established by the Khmer Rouge and the secret police known as the Santebal (literally "keeper of peace").

[2] On 26 July 2010, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia convicted the prison's chief, Kang Kek Iew, for crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions.

[4] To accommodate the victims of purges that were important enough for the attention of the Khmer Rouge, a new detention center was planned in the building that was formerly known as Tuol Svay Prey High School,[5][6] named after a royal ancestor of King Norodom Sihanouk.

In the early months of S-21's existence, most of the victims were from the previous Lon Nol regime and included soldiers, government officials, as well as academics, doctors, teachers, students, factory workers, monks, engineers, etc.

At some point between 1979 and 1980 the prison was reopened by the government of the People's Republic of Kampuchea as a historical museum memorializing the actions of the Khmer Rouge regime.

[5] The torture system at Tuol Sleng was designed to make prisoners confess to whatever crimes they were charged with by their captors.

Prisoners were routinely beaten and tortured with electric shocks, searing hot metal instruments and hanging, as well as through the use of various other devices.

Other methods for generating confessions included pulling out fingernails while pouring alcohol on the wounds, holding prisoners' heads under water, and the use of the waterboarding technique.

[5] Although many prisoners died from this kind of abuse, killing them outright was discouraged, since the Khmer Rouge needed their confessions.

[5] Typical confessions ran into thousands of words in which the prisoner would interweave true events in their lives with imaginary accounts of their espionage activities for the CIA, the KGB, or Vietnam.

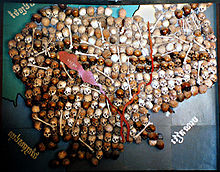

However, by the end of 1976, cadres ran out of burial spaces, and the prisoner and family members were taken to the Boeung Choeung Ek ("Crow's Feet Pond") extermination centre, fifteen kilometers from Phnom Penh.

[12] There, they were killed by a group of teenagers led by a Comrade Teng,[12] being battered to death with iron bars, pickaxes, machetes and many other makeshift weapons owing to the scarcity and cost of ammunition.

Though most of the foreign victims were either Vietnamese or Thai,[13] a number of Western prisoners, many picked up at sea by Khmer Rouge patrol boats, also passed through S-21 between April 1976 and December 1978.

Even though the vast majority of the victims were Cambodian, some were foreigners, including 488 Vietnamese, 31 Thai, four French, two Americans, two Australians, one Laotian, one Arab, one Briton, one Canadian, one New Zealander, and one Indonesian.

Two Franco-Vietnamese brothers named Rovin and Harad Bernard were detained in April 1976 after they were transferred from Siem Reap, where they had worked tending cattle.

[15] Another Frenchman named Andre Gaston Courtigne, a 30-year-old clerk and typist at the French embassy, was arrested the same month along with his Khmer wife in Siem Reap.

They were arrested by Khmer patrol boats, taken ashore, where they were blindfolded, placed on trucks, and taken to the then-deserted Phnom Penh.

Witnesses reported that a foreigner was burned alive; initially, it was suggested that this might have been John Dewhirst, but a survivor would later identify Kerry Hamill as the victim of this particular act of brutality.

[18][19] One of the last foreign prisoners to die was 29-year-old American Michael S. Deeds, who was captured with his friend Christopher E. DeLance on November 24, 1978, while sailing from Singapore to Hawaii.

The chief of the prison was Khang Khek Ieu (also known as Comrade Duch), a former mathematics teacher who worked closely with Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot.

Pon was the person who interrogated important people such as Keo Meas, Nay Sarann, Ho Nim, Tiv Ol, and Phok Chhay.

They were also forbidden to observe or eavesdrop on interrogations, and they were expected to obey 30 regulations, which barred them from such things as taking naps, sitting down or leaning against a wall while on duty.

They confessed to being lazy in preparing documents, to having damaged machines and various equipment, and to having beaten prisoners to death without permission when assisting with interrogations.

What follows is what is posted today at the Tuol Sleng Museum; the imperfect grammar is a result of faulty translation from the original Khmer: During testimony at the Khmer Rouge Tribunal on April 27, 2009, Duch claimed the ten security regulations were a fabrication of the Vietnamese officials that first set up the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum.

In 1979, Hồ Văn Tây, a Vietnamese combat photographer, was the first journalist to document Tuol Sleng to the world.

They are accompanied by paintings by former inmate Vann Nath showing people being tortured, which were added by the post-Khmer Rouge regime installed by the Vietnamese in 1979.

Along with the Choeung Ek Memorial (the Killing Fields), the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum is included as a point of interest for those visiting Cambodia.

[note 1] S-21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine is a 2003 film by Rithy Panh, a Cambodian-born, French-trained filmmaker who lost his family when he was 11.

The film features two Tuol Sleng survivors, Vann Nath and Chum Mey, confronting their former Khmer Rouge captors, including guards, interrogators, a doctor and a photographer.

The focus of the film is the difference between the feelings of the survivors, who want to understand what happened at Tuol Sleng to warn future generations, and the former jailers, who cannot escape the horror of the genocide they helped create.