Turabay dynasty

The Turabay dynasty (Arabic: آل طرباي, romanized: Āl Ṭurabāy) was a family of Bedouin emirs in northern Palestine who served as the multazims (tax farmers) and sanjak-beys (district governors) of Lajjun Sanjak during Ottoman rule in the 16th–17th centuries.

The progenitors of the family had served as chiefs of Marj ibn Amir (the Plain of Esdraelon or Jezreel Valley) under the Egypt-based Mamluks in the late 15th century.

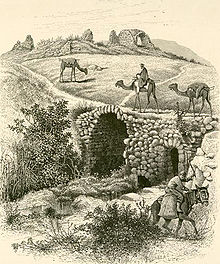

Although in the 17th century several of their emirs lived in the towns of Lajjun and Jenin, the Turabays largely preserved their nomadic way of life, pitching camp with their Banu Haritha tribesmen near Caesarea in the winters and the plain of Acre in the summers.

The eastward migration of the Banu Haritha to the Jordan Valley, Ottoman centralization drives, and diminishing tax revenues brought about their political decline and they were permanently stripped of office in 1677.

[5] In the 15th century, during Mamluk rule in Palestine (1260s–1516), the eponymous ancestor of the family, Turabay, was the chief of the Marj ibn Amir plain (commonly known today as the Jezreel Valley), an amal (subdistrict) of Mamlakat Safad (the province of Safed).

[6] By this time, the Banu Haritha dominated the regions of Marj ibn Amir and northern Jabal Nablus (Samaria), which collectively became referred to in Arabic as bilad al-Haritha (lit.

A further testament to Ottoman favor was Turabay's large iltizam (tax farm), which spanned several subdistricts in the sanjaks of Safed, Damascus and Ajlun, the revenues of which amounted to 516,855 akçes.

In 1552 the Turabays were accused of rebellion for acquiring illegal firearms and the authorities warned the sanjak-beys (sanjak governors) of Damascus Eyalet to prohibit their subjects dealings with the family.

[30] As well as Lajjun, in 1579, Assaf requested the governorship of Nablus, promising to pay the sanjak's tax arrears and build a watchtower between Qaqun and Jaljulia to secure that part of the highway from brigands.

[31] In 1594 he served as a temporary replacement for the sanjak-bey of Gaza, Ahmad Pasha ibn Ridwan, while the latter was away leading the Hajj pilgrim caravan and continued to govern Lajjun until his death in 1601.

[38] By this time, the Banu Haritha's dwelling areas spanned the coastal plain of Palestine around Qaqun to Kafr Kanna in the Lower Galilee and the surrounding hinterland.

[41] During the rebellion of Ali Janbulad, a Kurdish chief and governor of Aleppo, and Fakhr al-Din against the Ottomans in Syria in 1606, Ahmad generally remained neutral.

[42] Interested in weakening his powerful neighbor to the north, Ahmad joined the government campaign of Hafiz Ahmed Pasha against Fakhr al-Din and his Ma'n dynasty in Mount Lebanon in 1613–1614, which prompted the Druze chief's flight to Europe.

[46] Ahmad's granddaughter (unnamed in the sources) was wed to Muhammad ibn Farrukh to consolidate their families' alliance in the lead-up to their confrontation against Fakhr al-Din in 1623.

[48] Fakhr al-Din responded to the Turabays' support for his replacements by dispatching troops to capture the tower of Haifa and burn villages in Mount Carmel, both places in Ahmad's jurisdiction which were hosting Shia refugees from Safed Sanjak.

[51] Fakhr al-Din soon after had to contend with a campaign by Mustafa Pasha, the beylerbey of Damascus, allowing Ahmad to clear Lajjun Sanjak of the residual Ma'nid presence.

[45][40] Fakhr al-Din defeated and captured Mustafa Pasha in the Battle of Anjar later that year and extracted from the beylerbey the appointment of his son Mansur as sanjak-bey of Lajjun.

[45] Later that month Ahmad and his ally Muhammad ibn Farrukh defeated Fakhr al-Din in battle and shortly after dislodged the Ma'nid sekbans stationed in Jenin.

[53] At different times during his governorship, his brothers Azzam and Muhammad and son Zayn Bey held timars and ziamets (both being types of imperial land grants) in Lajjun Sanjak's subdistricts of Atlit, Shara and Shafa.

The fortunes of the family began to deteriorate under his leadership, though he continued to successfully perform his duties as sanjak-bey, protecting the roads and helping suppress a peasants' revolt in Nablus Sanjak.

[54] D'Arvieux was dispatched by the French consul of Sidon in August 1664 to request Muhammad facilitate the reestablishment of Carmelite Order monks in Mount Carmel.

[i] The Porte had become increasingly concerned with the local dynasties due to diminishing tax revenues from their sanjaks and the loss of control of the Hajj caravan routes.

The Turabays, Ridwans and Farrukhs considered Palestine their collective fiefdom and resisted imperial attempts to weaken their control, while being careful not to openly rebel against the Porte.

[60] With the imprisonment and execution of the Ridwan governor of Gaza, Husayn Pasha, in 1662/63, and the mysterious death of the sanjak-bey of Nablus, Assaf Farrukh, on his way to Constantinople in 1670/71, the alliance of the three dynasties was fatally weakened.

[64] Sharon attributes the decline of the Turabays to the eastward migration of their power base, the Banu Haritha, to the Jordan Valley and the Ajlun region in the late 17th century.

[5] The Turabay emirs ignored their official duty as sanjak-beys to participate in imperial wars upon demand,[75] but they generally remained loyal to the Ottomans in Syria, including during the peak of Fakhr al-Din's power.

[79] According to Sharon, the Turabays "introduced two innovations" to their traditional way of life "as a mark of their official status": the employment of a secretary to handle their correspondences and the use of a military band (composed of tambourines, oboes, drums and trumpets).

[28] It was described by a British Mandatory antiquities inspector in 1941 as a ruined domed chamber housing the tombstone of the emir with a two-line inscription reading: Basmalah [in the name of God].

[70] According to Abu-Husayn, they maintained the favor of the Ottomans by "properly attending to the administrative and guard duties assigned to them" and served as an "example of a dynasty of Bedouin chiefs who managed to perpetuate their control over a given region".

[58] They stood in contrast to their Bedouin contemporaries, the Furaykhs of the Beqaa Valley, who used initial imperial favor to enrich themselves at the expense of the proper governance of their territory.