Turbocharger

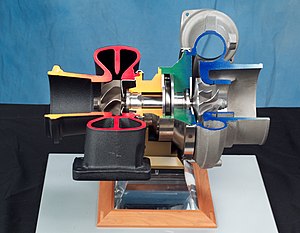

In an internal combustion engine, a turbocharger (also known as a turbo or a turbosupercharger) is a forced induction device that is powered by the flow of exhaust gases.

[5] Then in 1885, Gottlieb Daimler patented the technique of using a gear-driven pump to force air into an internal combustion engine.

[7][8][9] This patent was for a compound radial engine with an exhaust-driven axial flow turbine and compressor mounted on a common shaft.

[10][11] The first prototype was finished in 1915 with the aim of overcoming the power loss experienced by aircraft engines due to the decreased density of air at high altitudes.

[15] This was followed very closely in 1925, when Alfred Büchi successfully installed turbochargers on ten-cylinder diesel engines, increasing the power output from 1,300 to 1,860 kilowatts (1,750 to 2,500 hp).

[16][17][18] This engine was used by the German Ministry of Transport for two large passenger ships called the Preussen and Hansestadt Danzig.

[10][19] Other early turbocharged airplanes included the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, Lockheed P-38 Lightning, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and experimental variants of the Focke-Wulf Fw 190.

In Formula One, capacity was limited to only 1.5 litre, with the first race victories coming in the late 1970s, and the first F1 World Championship in 1983, with a BMW M10-based 4-cylinder engine that dates back to 1961.

[10] Like other forced induction devices, a compressor in the turbocharger pressurises the intake air before it enters the inlet manifold.

The scavenging effect of these gas pulses recovers more energy from the exhaust gases, minimizes parasitic back losses and improves responsiveness at low engine speeds.

Because of this, variable-geometry turbochargers often have reduced lag, a lower boost threshold, and greater efficiency at higher engine speeds.

An electrically-assisted turbocharger combines a traditional exhaust-powered turbine with an electric motor, in order to reduce turbo lag.

such as mild hybrid integration,[39] have enabled turbochargers to start spooling before exhaust gases provide adequate pressure.

This can further reduce turbo lag[40] and improve engine efficiency, especially during low-speed driving and frequent stop-and-go conditions seen in urban areas.

The compressor draws in outside air through the engine's intake system, pressurises it, then feeds it into the combustion chambers (via the inlet manifold).

Some turbochargers use a "ported shroud", whereby a ring of holes or circular grooves allows air to bleed around the compressor blades.

[47][48] This delay is due to the increasing exhaust gas flow (after the throttle is suddenly opened) taking time to spin up the turbine to speeds where boost is produced.

Some engines use multiple turbochargers, usually to reduce turbo lag, increase the range of rpm where boost is produced, or simplify the layout of the intake/exhaust system.