Common blackbird

Both sexes are territorial on the breeding grounds, with distinctive threat displays, but are more gregarious during migration and in wintering areas.

This common and conspicuous species has given rise to a number of literary and cultural references, frequently related to its song.

The common blackbird was described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Turdus merula (characterised as T. ater, rostro palpebrisque fulvis).

[6] About 65 species of medium to large thrushes are in the genus Turdus, characterised by rounded heads, longish, pointed wings, and usually melodious songs.

[8] It may not immediately be clear why the name "blackbird", first recorded in 1486, was applied to this species, but not to one of the various other common black English birds, such as the carrion crow, raven, rook, or jackdaw.

Another variant occurs in Act 3 of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, where Bottom refers to "The Woosell cocke, so blacke of hew, With Orenge-tawny bill".

[8] The Central Asian subspecies, the relatively large intermedius, also differs in structure and voice, and may represent a distinct species.

[11] The common blackbird of the nominate subspecies T. m. merula is 23.5–29 cm (9.3–11.4 in) in length, has a long tail, and weighs 80–125 g (2.8–4.4 oz).

[8] The common blackbird breeds in temperate Eurasia, North Africa, the Canary Islands, and South Asia.

[21] Recoveries of blackbirds ringed on the Isle of May show that these birds commonly migrate from southern Norway (or from as far north as Trondheim) to Scotland, and some onwards to Ireland.

[29] As long as winter food is available, both the male and female will remain in the territory throughout the year, although occupying different areas.

[16] The male common blackbird attracts the female with a courtship display which consists of oblique runs combined with head-bowing movements, an open beak, and a "strangled" low song.

[31] The nominate T. merula may commence breeding in March, but eastern and Indian races are a month or more later, and the introduced New Zealand birds start nesting in August (late winter).

[8][25] The breeding pair prospect for a suitable nest site in a creeper or bush, favouring evergreen or thorny species such as ivy, holly, hawthorn, honeysuckle or pyracantha.

The male's song is a varied and melodious low-pitched fluted warble, given from trees, rooftops or other elevated perches[37] mainly in the period from March to June, sometimes into the beginning of July.

[39] At least two subspecies, T. m. merula and T. m. nigropileus, will mimic other species of birds, cats, humans or alarms, but this is usually quiet and hard to detect.

Near human habitation the main predator of the common blackbird is the domestic cat, with newly fledged young especially vulnerable.

[42][43] However, there is little direct evidence to show that either predation of the adult blackbirds or loss of the eggs and chicks to corvids, such as the European magpie or Eurasian jay, decrease population numbers.

The benefit of this is that the bird can rest in areas of high predation or during long migratory flights, but still retain a degree of alertness.

[52] In the western Palearctic, populations are generally stable or increasing,[16] but there have been local declines, especially on farmland, which may be due to agricultural policies that encouraged farmers to remove hedgerows (which provide nesting places), and to drain damp grassland and increase the use of pesticides, both of which could have reduced the availability of invertebrate food.

[53][55] The introduced common blackbird is, together with the native silvereye (Zosterops lateralis), the most widely distributed avian seed disperser in New Zealand.

Introduced there along with the song thrush (Turdus philomelos) in 1862, it has spread throughout the country up to an elevation of 1,500 metres (4,921 ft), as well as outlying islands such as the Campbell and Kermadecs.

[56] It eats a wide range of native and exotic fruit, and makes a major contribution to the development of communities of naturalised woody weeds.

The common blackbird was seen as a sacred though destructive bird in Classical Greek folklore, and was said to die if it consumed pomegranates.

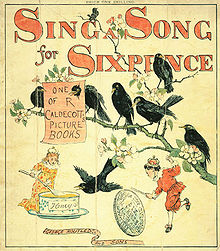

[60] Like many other small birds, it has in the past been trapped in rural areas at its night roosts as an easily available addition to the diet,[61] and in medieval times the practice of placing live birds under a pie crust just before serving may have been the origin of the familiar nursery rhyme:[61] Sing a song of sixpence, A pocket full of rye; Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie!

[63]In the English Christmas carol "The Twelve Days of Christmas", the line commonly sung today as "four calling birds" is believed to have originally been written in the 18th century as "four colly birds", an archaism meaning "black as coal" that was a popular English nickname for the common blackbird.

[64] The common blackbird, unlike many black creatures, is not normally seen as a symbol of bad luck,[61] but R. S. Thomas wrote that there is "a suggestion of dark Places about it",[65] and it symbolised resignation in the 17th century tragic play The Duchess of Malfi;[66] an alternate connotation is vigilance, the bird's clear cry warning of danger.

[69] French composer Olivier Messiaen transcribed the songs of male blackbirds; these melodies have commonly appeared throughout his œuvre.