The Turn of the Screw

The Turn of the Screw is an 1898 gothic horror novella by Henry James which first appeared in serial format in Collier's Weekly from January 27 to April 16, 1898.

Initial reviews regarded it only as a frightening ghost story, but, in the 1930s, some critics suggested that the supernatural elements were figments of the governess' imagination.

The boy, Miles, is attending a boarding school, while his younger sister, Flora, is living in Bly, where she is cared for by Mrs. Grose, the housekeeper.

Flora's uncle, the governess's new employer, is uninterested in raising the children and gives her full charge, explicitly stating that she is not to bother him with communications of any sort.

Before their deaths, Jessel and Quint spent much of their time with Flora and Miles, and the governess becomes convinced that the two children are aware of the ghosts' presence and influenced by them.

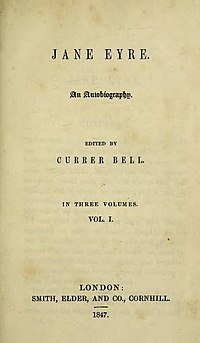

[2] The novella alludes to Jane Eyre in tandem with an explicit reference to Ann Radcliffe's Gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), wherein the governess wonders if there might be a secret relative hidden in the attic at Bly.

[5] Similarly, the novella foregoes major devices associated with Gothic novels, such as digressions, as in Frankenstein (1818) and Dracula (1897), instead relating one whole, continuous narrative.

L. Andrew Cooper observed that The Turn of the Screw might be the best-known example of a ghost story which exploits the ambiguity of a first-person narrative.

[8] Citing James' reference to the work as his "designed horror", Donald P. Costello suggested that the effect of a given scene varies depending on who represents the action.

His health had also worsened, with advancing gout,[15] and several of his close friends had died: his sister and diarist Alice James, and writers Robert Louis Stevenson and Constance Fenimore Woolson.

[17] In an entry in his journal from January 12, 1895, James recounts a ghost story told to him by Edward White Benson, the archbishop of Canterbury, while visiting him for tea at his home two days earlier.

The story bears a striking resemblance to what would eventually become The Turn of the Screw, with depraved servants corrupting young children before and after their deaths.

[27] In October 1898, the novella appeared with the short story "Covering End" in a volume titled The Two Magics, published by Macmillan in New York City and by Heinemann in London.

[35] Scholar Terry Heller notes that the children featured prominently in early criticism because the novella violated a Victorian presumption of childhood innocence.

[38] In a 1918 essay, Virginia Woolf wrote that Miss Jessel and Peter Quint possessed "neither the substance nor independent existence of ghosts".

[39] Woolf did not suggest that the ghosts were hallucinations, but—in a similar fashion to other early critics—said they represented the governess' growing awareness of evil in the world.

[45] A book-length close reading of the text was produced in 1965 using Wilson's Freudian analysis as a foundation; it characterised the governess as increasingly mad and hysterical.

[48] Robert B. Heilman was a prominent advocate for the apparitionist interpretation; he saw the story as a Hawthornesque allegory about good and evil, and the ghosts as active agents to that effect.

[49] Scholars critical of Wilson's essay pointed to Douglas' positive account of the governess's character in the prologue, long after her death.

[49] The second point led Wilson to "retract his thesis (temporarily)";[48] in a later revision of his essay, he argued the governess had been made aware of another male at Bly by Mrs Grose.

[51][52] Todorov emphasised the importance of "hesitation" in stories with supernatural elements, and critics found an abundance of them within James' novella.

[57] This is still a position held by many critics, such as Giovanni Bottiroli [it], who argues that evidence for the intended ambiguity of the text can be found at the beginning of the novella, where Douglas tells his fictional audience that the governess had never told anyone but himself about the events that happened at Bly, and that they "would easily judge" why.

Paula Marantz Cohen positively compares James' treatment of the governess to Sigmund Freud's writing about a young woman named Dora.

Cohen likens the way that Freud transforms Dora into merely a summary of her symptoms to how critics such as Edmund Wilson reduced the governess to a case of neurotic sexual repression.

[65] Other feature film adaptations include Rusty Lemorande's 1992 eponymous adaptation (set in the 1960s);[72] Eloy de la Iglesia's Spanish language Otra vuelta de tuerca (The Turn of the Screw, 1985);[67] Presence of Mind (1999), directed by Atoni Aloy; and In a Dark Place (2006), directed by Donato Rotunno.

[78] Literary references to and influences by The Turn of the Screw identified by the James scholar Adeline R. Tintner include The Secret Garden (1911), by Frances Hodgson Burnett; "Poor Girl" (1951), by Elizabeth Taylor; The Peacock Spring (1975), by Rumer Godden; Ghost Story (1975) by Peter Straub; "The Accursed Inhabitants of House Bly" (1994) by Joyce Carol Oates; and Miles and Flora (1997)—a sequel—by Hilary Bailey.

[79] Further literary adaptations identified by other authors include Affinity (1999), by Sarah Waters; A Jealous Ghost (2005), by A. N. Wilson;[80] Florence & Giles (2010), by John Harding;[65] and Maybe This Time (2010) by Jennifer Crusie.

In the story, the ghosts of Quentin Collins and Beth Chavez haunted the west wing of Collinwood, possessing the two children living in the mansion.