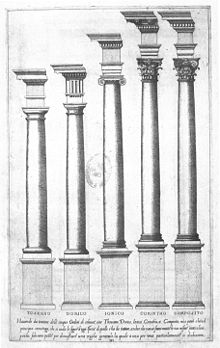

Tuscan order

Serlio found it "suitable to fortified places, such as city gates, fortresses, castles, treasuries, or where artillery and ammunition are kept, prisons, seaports and other similar structures used in war."

[3] Giorgio Vasari made a valid argument for this claim by reference to Il Cronaca's graduated rustication on the facade of Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

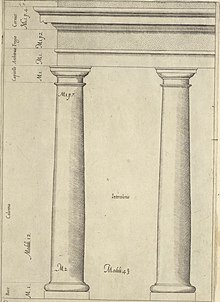

Palladio agreed in essence with Serlio: The Tuscan, being rough, is rarely used above ground except in one-storey buildings like villa barns or in huge structures like Amphitheatres and the like which, having many orders, can take this one in place of the Doric, under the Ionic.

A striking feature is his rusticated frieze resting upon a perfectly plain entablature[10] Examples of the use of the order are the Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome, by Baldassarre Peruzzi, 1532–1536, and the pronaos portico to Santa Maria della Pace added by Pietro da Cortona (1656–1667).

Though in most respects the Greek temple frontage is a careful exercise in revivalism, there are minimal plain bases to the thick fluted columns and, despite having metope reliefs and a large group of sculpture in the pediment, there are no triglyphs or guttae.

Because the Tuscan mode is easily worked up by a carpenter with a few planing tools, it became part of the vernacular Georgian style that lingered in places like New England and Ohio deep into the 19th century.