Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Bill 2008

It was in large part a revision of the text of the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe after its rejection in referendums in France in May 2005 and in the Netherlands in June 2005.

[2] The Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution Bill was proposed in Dáil Éireann by Minister for Foreign Affairs Dermot Ahern on 2 April 2008.

[3] It passed final stages in the Dáil on 29 April, with Sinn Féin TDs and Independent TD Tony Gregory rising against, but with insufficient numbers to call a vote.

The invitation by UCD's Law Society to French far-right politician Jean-Marie Le Pen was seen as an example of this.

[14] On 12 March 2008, Libertas, a lobby group started by businessman Declan Ganley launched a campaign called Facts, not politics which advocated a No vote in the referendum.

[15] A month later, the German Chancellor, Angela Merkel appealed to Irish people to vote Yes in the referendum whilst on a visit to Ireland.

[17] At the start of May, the Irish Alliance for Europe launched its campaign for a Yes vote in the referendum this consisted of trade unionists, business people, academics and politicians.

By the start of June, Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Labour Party had united in their push for a Yes vote despite earlier divisions.

[21] The two largest farming organisations, the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers Association (ICMSA)[22] and the Irish Farmers' Association[23] called for a Yes vote, the latter giving its support after assurances from the Taoiseach Brian Cowen that Ireland would use its veto in Europe if a deal on World Trade reform was unacceptable.

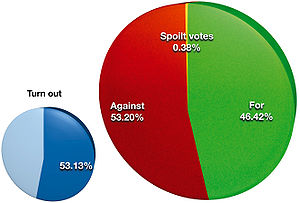

The overall verdict was formally announced by the Referendum Returning officer in Dublin Castle by accumulating the constituency totals.

[1] The national result was as follows: Ireland had begun to cast a sceptical[39] eye on the EU and general concerns about how Europe was developing were raised.

Consequently, issues such as abortion,[48][49] [50] tax,[51] euthanasia,[52] the veto,[48][53] EU directives,[54] qualified majority voting,[55] Ireland's commissioner,[56] detention of three-year-olds,[48] the death penalty,[57] Euroarmy conscription,[58] gay marriage,[59] immigration,[48][60] nuclear energy,[61] workers' rights,[61] sovereignty,[62] and neutrality[63] were raised, some of which were spurious[48][64] or actually dealt with by the Treaty of Nice.

[65] The "No" faction could fight on whichever terrain they wished[66] and could give positive reasons for rejecting the treaty, such as the possibility of renegotiation.

[41] In September 2008 rumours in Brussels indicated that US billionaires and neocons heavily influenced the Irish vote by sponsoring the "No" campaigns, particularly those of Declan Ganley's Libertas lobby group.

However, the British conservative MEP Jonathan Evans reported to EUobserver on 9 December 2008 after returning from a European Parliament delegation to the US, "[o]ur congressional colleagues drew our attention to a statement from US deputy secretary of state John Negroponte at Trinity College Dublin on 17 November, completely refuting the suggestion of any US dimension whatsoever".

French Europe Minister Jean-Pierre Jouyet blamed "American neoconservatives" for the Irish voter's rejection of the treaty.

[75] In the meeting of the European Council (the meeting of the heads of government of all twenty-seven European Union member states) in Brussels on 11–12 December 2008, Taoiseach Brian Cowen presented the concerns of the Irish people relating to taxation policy, family, social and ethical issues, and Ireland's policy of neutrality.

The guarantee that Ireland would keep its Commissioner provided Lisbon was ratified was criticised in the Irish Times[78] on the grounds that it may lead to an oversized European Commission.

Official websites Unofficial consolidated treaties Media overviews Political party campaigns Groups Articles

All figures rounded to nearest digit.