Nuclear weapon design

Given the speed of the fragments and the mean free path between nuclei in the compressed fuel assembly (for the implosion design), this takes about a millionth of a second (a microsecond), by which time the core and tamper of the bomb have expanded to a ball of plasma several meters in diameter with a temperature of tens of millions of degrees Celsius.

[citation needed] The only practical way to capture most of the fusion energy is to trap the neutrons inside a massive bottle of heavy material such as lead, uranium, or plutonium.

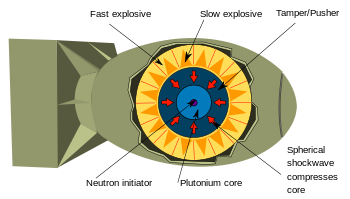

Early weapons used a modulated neutron generator code named "Urchin" inside the pit containing polonium-210 and beryllium separated by a thin barrier.

In modern weapons, the neutron generator is a high-voltage vacuum tube containing a particle accelerator which bombards a deuterium/tritium-metal hydride target with deuterium and tritium ions.

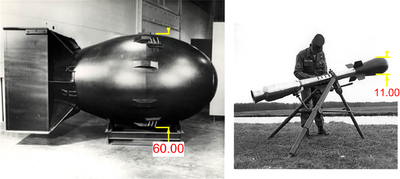

Analysis shows that less than 2% of the uranium mass underwent fission;[17] the remainder, representing most of the entire wartime output of the giant Y-12 factories at Oak Ridge, scattered uselessly.

[citation needed] Because plutonium is chemically reactive it is common to plate the completed pit with a thin layer of inert metal, which also reduces the toxic hazard.

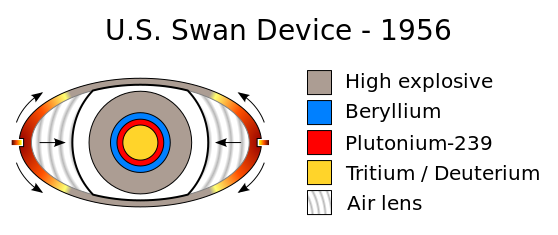

A simpler solid-pit design was considered more reliable, given the time constraints, but it required a heavy U-238 tamper, a thick aluminium pusher, and three tons of high explosives.

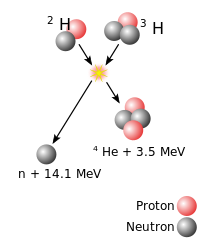

The key to achieving faster fission would be to introduce more neutrons, and among the many ways to do this, adding a fusion reaction was relatively easy in the case of a hollow pit.

[citation needed] Since a nuclear explosion is supercritical, any extra neutrons will be multiplied by the chain reaction, so even tiny quantities introduced early can have a large effect on the outcome.

For this reason, even the relatively low compression pressures and times (in fusion terms) found in the center of a hollow pit warhead are enough to create the desired effect.

[citation needed] RI was a particular problem before effective early warning radar systems because a first strike attack might make retaliatory weapons useless.

[citation needed] In engineering terms, radiation implosion allows for the exploitation of several known features of nuclear bomb materials which heretofore had eluded practical application.

[citation needed] Its first mention in a U.S. government document formally released to the public appears to be a caption in a graphic promoting the Reliable Replacement Warhead Program in 2007.

Third generation[48][49][50] nuclear weapons are experimental special effect warheads and devices that can release energy in a directed manner, some of which were tested during the Cold War but were never deployed.

Following the concern caused by the estimated gigaton scale of the 1994 Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 impacts on the planet Jupiter, in a 1995 meeting at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), Edward Teller proposed to a collective of U.S. and Russian ex-Cold War weapons designers that they collaborate on designing a 1,000-megaton nuclear explosive device for diverting extinction-class asteroids (10+ km in diameter), which would be employed in the event that one of these asteroids were on an impact trajectory with Earth.

[citation needed] Commonly misconceived as a weapon designed to kill populations and leave infrastructure intact, these bombs (as mentioned above) are still very capable of leveling buildings over a large radius.

[citation needed] At Los Alamos, it was found in April 1944 by Emilio Segrè that the proposed Thin Man Gun assembly type bomb would not work for plutonium because of predetonation problems caused by Pu-240 impurities.

The main wartime job at Los Alamos was the experimental determination of critical mass, which had to wait until sufficient amounts of fissile material arrived from the production plants: uranium from Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and plutonium from the Hanford Site in Washington.

[citation needed] Starting with the Nova facility at Livermore in the mid-1980s, nuclear design activity pertaining to radiation-driven implosion was informed by research with indirect drive laser fusion.

In a nuclear explosion, a large number of discrete events, with various probabilities, aggregate into short-lived, chaotic energy flows inside the device casing.

A probe inside a test device could transmit information by heating a plate of metal to incandescence, an event that could be recorded by instruments located at the far end of a long, very straight pipe.

[75] From the shot cab, the pipes turned horizontally and traveled 2.3 km (7,500 ft) along a causeway built on the Bikini reef to a remote-controlled data collection bunker on Namu Island.

[citation needed] The global alarm over radioactive fallout, which began with the Castle Bravo event, eventually drove nuclear testing literally underground.

During the next three decades, until September 23, 1992, the United States conducted an average of 2.4 underground nuclear explosions per month, all but a few at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) northwest of Las Vegas.

[citation needed] The Yucca Flat section of the NTS is covered with subsidence craters resulting from the collapse of terrain over radioactive caverns created by nuclear explosions (see photo).

[citation needed] The Y-12 plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where mass spectrometers called calutrons had enriched uranium for the Manhattan Project, was redesigned to make secondaries.

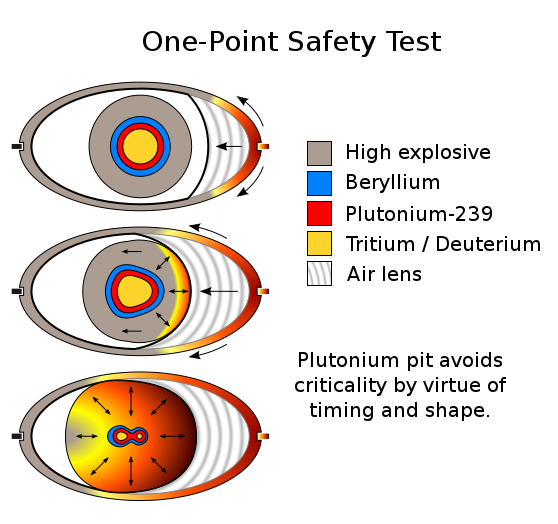

[citation needed] It is inherently dangerous to have a weapon containing a quantity and shape of fissile material which can form a critical mass through a relatively simple accident.

[citation needed] Neither of these effects is likely with implosion weapons since there is normally insufficient fissile material to form a critical mass without the correct detonation of the lenses.

[citation needed] Alternatively, the pit can be "safed" by having its normally hollow core filled with an inert material such as a fine metal chain, possibly made of cadmium to absorb neutrons.

[citation needed] In the last test before the 1958 moratorium the W47 warhead for the Polaris SLBM was found to not be one-point safe, producing an unacceptably high nuclear yield of 200 kg (440 lb) of TNT equivalent (Hardtack II Titania).

- Warhead before firing. The nested spheres at the top are the fission primary; the cylinders below are the fusion secondary device.

- Fission primary's explosives have detonated and collapsed the primary's fissile pit .

- The primary's fission reaction has run to completion, and the primary is now at several million degrees and radiating gamma and hard X-rays, heating up the inside of the hohlraum , the shield, and the secondary's tamper.

- The primary's reaction is over and it has expanded. The surface of the pusher for the secondary is now so hot that it is also ablating or expanding away, pushing the rest of the secondary (tamper, fusion fuel, and fissile spark plug) inward. The spark plug starts to fission. Not depicted: the radiation case is also ablating and expanding outward (omitted for clarity of diagram).

- The secondary's fuel has started the fusion reaction and shortly will burn up. A fireball starts to form.