Two Treatises of Government

The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government) is a work of political philosophy published anonymously in 1689 by John Locke.

[4] According to Laslett, Locke was writing his Two Treatises during the Exclusion Crisis, which attempted to prevent James II from ever taking the throne in the first place.

[9] Peter Laslett maintains that, while Locke may have added or altered some portions in 1689, he did not make any revisions to accommodate for the missing section; he argues, for example, that the end of the First Treatise breaks off in mid-sentence.

Before publication, however, Locke gave it greater prominence by (hastily) inserting a separate title page: "An Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent and End of Civil Government.

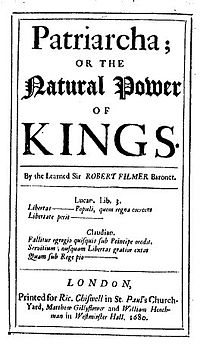

"[13] The First Treatise is focused on the refutation of Sir Robert Filmer, in particular his Patriarcha, which argued that civil society was founded on divinely sanctioned patriarchalism.

Locke proceeds through Filmer's arguments, contesting his proofs from Scripture and ridiculing them as senseless, until concluding that no government can be justified by an appeal to the divine right of kings.

Locke begins by describing the state of nature, and appeals to god's creative intent in his case for human equality in this primordial context.

Locke chose Filmer as his target, he says, because of his reputation and because he "carried this Argument [jure divino] farthest, and is supposed to have brought it to perfection" (1st Tr., § 5).

Accepting that fatherhood grants authority, he argues, it would do so only by the act of begetting, and so cannot be transmitted to one's children because only God can create life.

Nor could Adam, or his heir, leverage this grant to enslave mankind, for the law of nature forbids reducing one's fellows to a state of desperation, if one possesses a sufficient surplus to maintain oneself securely.

Locke intimates in the First Treatise that the doctrine of divine right of kings (jure divino) will eventually be the downfall of all governments.

They have no relationship of subordination or subjection unless God (the lord and master of them all) had clearly set one person above another and conferred on him an undoubted right to dominion and sovereignty.

[14][15] In 17th-century England, the work of Thomas Hobbes popularized theories based upon a state of nature, even as most of those who employed such arguments were deeply troubled by his absolutist conclusions.

Finally, the proper alternative to the natural state is not political dictatorship/tyranny but a government that has been established with consent of the people and the effective protection of basic human rights to life, liberty, and property under the rule of law.

16 ("Of Conquest") are sources of some confusion: the former provides a justification for slavery that can nonetheless never be met, and thus constitutes an argument against the institution, the latter concerns the rights of conquerors, which Locke seeks to challenge.

Most scholars take this to be Locke's point regarding slavery: submission to absolute monarchy is a violation of the law of nature, for one does not have the right to enslave oneself.

The legitimacy of an English king depended on (somehow) demonstrating descent from William the Conqueror: the right of conquest was therefore a topic rife with constitutional connotations.

Locke does not say that all subsequent English monarchs have been illegitimate, but he does make their rightful authority dependent solely upon their having acquired the people's approbation.

Locke first argues that, clearly, aggressors in an unjust war can claim no right of conquest: everything they despoil may be retaken as soon as the dispossessed have the strength to do so.

"[17] In A Letter Concerning Toleration, he wrote that the magistrate's power was limited to preserving a person's "civil interest", which he described as "life, liberty, health, and indolency of body; and the possession of outward things".

[18] By saying that political society was established for the better protection of property, he claims that it serves the private (and non-political) interests of its constituent members: it does not promote some good that can be realised only in community with others (e.g. virtue).

(sec 140) His notions of people's rights and the role of civil government provided strong support for the intellectual movements of both the American and French Revolutions.

Locke affirmed an explicit right to revolution in Two Treatises of Government: “whenever the Legislators endeavor to take away, and destroy the Property of the People, or to reduce them to Slavery under Arbitrary Power, they put themselves into a state of War with the People, who are thereupon absolved from any farther Obedience, and are left to the common Refuge, which God hath provided for all Men, against Force and Violence.

As Mark Goldie explains: "Leviathan was a monolithic and unavoidable presence for political writers in Restoration England in a way that in the first half of the eighteenth the Two Treatises was not.

[23] Not only did patriarchalism continue to be a legitimate political theory in the 18th century, but as J. G. A. Pocock and others have gone to great lengths to demonstrate, so was civic humanism and classical republicanism.

[27] By 1815, Locke's portrait was taken down from Christ Church, his alma mater (it was later restored to a position of prominence, and currently hangs in the dining hall of the college).

[30] Thomas Pangle and Michael Zuckert have countered, demonstrating numerous elements in the thought of more influential founders that have a Lockean pedigree.

[37] C. B. Macpherson argued in his Political Theory of Possessive Individualism that Locke sets the stage for unlimited acquisition and appropriation of property by the powerful creating gross inequality.

In his A Discourse on Property, Tully describes Locke's view of man as a social dependent, with Christian sensibilities, and a God-given duty to care for others.

[41] Huyler finds that Locke explicitly condemned government privileges for rich, contrary to Macpherson's pro-capitalism critique, but also rejected subsidies to aid the poor, in contrast to Tully's social justice apologetics.