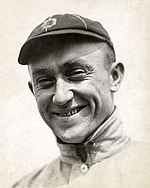

Ty Cobb

[15] Cobb's reputation, which includes a large college scholarship fund for Georgia residents financed by his early investments in Coca-Cola and General Motors, has been somewhat tarnished by allegations of racism and violence.

[25] By most accounts, he became fascinated with baseball as a child, and decided that he wanted to go professional one day; his father was vehemently opposed to this idea, but by his teenage years, he was trying out for area teams.

"[27] After joining the Steelers for a monthly salary of $50, Cobb promoted himself by sending several postcards written about his talents under different aliases to Grantland Rice, the Atlanta Journal sports editor.

Eventually, Rice wrote a small note in the Journal that a "young fellow named Cobb seems to be showing an unusual lot of talent.

[16] Court records indicate that William Cobb had suspected Amanda of infidelity[35] and was sneaking past his own bedroom window to catch her in the act.

By the time he died, he held over 20,000 shares of stock and owned bottling plants in Santa Maria, California, Twin Falls, Idaho, and Bend, Oregon.

[54] In the offseason between 1907 and 1908, Cobb negotiated with Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina, offering to coach baseball there "for $250 a month, provided that he did not sign with Detroit that season."

[57] In the same season, Charles M. Conlon snapped the famous photograph of a grimacing Cobb sliding into third base amid a cloud of dirt, which visually captured the grit and ferocity of his playing style.

Later it was rumored that the opposing manager had instructed his third baseman to play extra deep to allow Lajoie to win the batting race over the generally disliked Cobb.

Cobb led the AL that year in numerous other categories, including 248 hits, 147 runs scored, 127 RBI, 83 stolen bases, 47 doubles, 24 triples and a .621 slugging percentage.

"[51] In the same interview, Cobb talked about having noticed a throwing tendency of first baseman Hal Chase but having to wait two full years until the opportunity came to exploit it.

On May 15, 1912, Cobb assaulted a heckler, Claude Lucker (often misspelled as Lueker), in the stands in New York's Hilltop Park where the Tigers were playing the Highlanders.

Lucker, described by baseball historian Frank Russo as "a Tammany Hall lackey and two-bit punk," often berated Cobb when Detroit visited New York.

"[67] Cobb, in his discussion of the incident in the Holmes biography,[68] avoided such explicit words but alluded to Lucker's epithet by saying he was "reflecting on my mother's color and morals."

Other notable baseball stars who assaulted heckling fans include Babe Ruth, Cy Young, Rube Waddell, Kid Gleason, Sherry Magee, and Fred Clarke.

[76] On August 13, 1912, the same day the Tigers were to play the New York Highlanders at Hilltop Park, Cobb and his wife were driving to a train station in Syracuse that was to transport him to the game when three intoxicated men had stopped him on the way.

Based on a story by sports columnist Grantland Rice, the film casts Cobb as "himself," a small-town Georgia bank clerk with a talent for baseball.

In October 1918, Cobb enlisted in the Chemical Corps branch of the United States Army and was sent to the Allied Expeditionary Forces headquarters in Chaumont, France.

"[51] Tigers owner Frank Navin tapped Cobb to take over for Hughie Jennings as manager for the 1921 season, a deal he signed on his 34th birthday for $32,500 (equivalent to approximately $555,168 in today's terms[89]).

from the Medical College of South Carolina and practiced obstetrics and gynecology in Dublin, Georgia, until his death at 42 on September 9, 1952, from a brain tumor, his father remained distant.

According to sportswriter Grantland Rice, he and Cobb were returning from the Masters golf tournament in the late 1940s and stopped at a Greenville, South Carolina, liquor store.

Cobb noticed that the man behind the counter was "Shoeless" Joe Jackson, who had been banned from baseball almost 30 years earlier following the Black Sox scandal.

He also established the Cobb Educational Fund, which awarded scholarships to needy Georgia students bound for college, by endowing it with a $100,000 donation in 1953 (equivalent to approximately $1,138,806 in current year dollars [89]).

In 2010, an article by William R. "Ron" Cobb (no relation) in the peer-reviewed The National Pastime (the official publication of the Society for American Baseball Research) accused Stump of extensive forgeries of Cobb-related documents and diaries.

The historian Steven Elliott Tripp has explored the public's reaction to Cobb as a pioneer sports celebrity and "a player fans loved to hate.

"[138] Tripp writes that Cobb was both loved and hated as a representative of a particular kind of masculinity on the field, inviting male spectators to participate in the contest through taunts directed at opposing players.

[141][142] Some historians, including Wesley Fricks, Dan Holmes, and Charles Leerhsen, have defended Cobb against unfair portrayals of him in popular culture since his death.

[147] Following Campanella's accident that left him paralyzed, the Dodgers staged a tribute game where tens of thousands of spectators silently held lit matches above their heads.

"[150] Leerhesen also notes Cobb was the "main defender and patron" of Ulysses Simon Harrison, an African-American youth who was the Tigers' mascot from 1908 to 1910 under the name "L'il Rastus".

[161][162] All sources with standing agree that Cobb's lifetime batting average is .366 (except MLB.com, see below); some show slightly different numbers for at-bats and hits, but all devolve to .366.