Type II supernova

The degeneracy pressure of electrons and the energy generated by these fusion reactions are sufficient to counter the force of gravity and prevent the star from collapsing, maintaining stellar equilibrium.

The star fuses increasingly higher mass elements, starting with hydrogen and then helium, progressing up through the periodic table until a core of iron and nickel is produced.

When the compacted mass of the inert core exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.4 M☉, electron degeneracy is no longer sufficient to counter the gravitational compression.

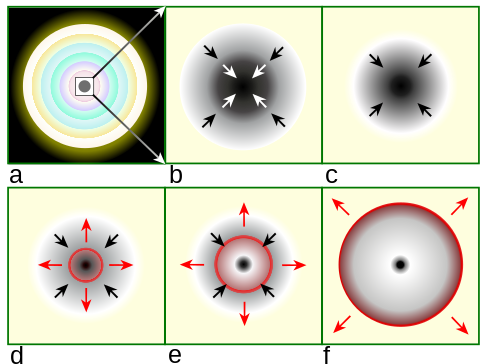

The collapse of the inner core is halted by the repulsive nuclear force and neutron degeneracy, causing the implosion to rebound and bounce outward.

The energy of this expanding shock wave is sufficient to disrupt the overlying stellar material and accelerate it to escape velocity, forming a supernova explosion.

The shock wave and extremely high temperature and pressure rapidly dissipate but are present for long enough to allow for a brief period during which the production of elements heavier than iron occurs.

This contraction raises the temperature high enough to allow a shorter phase of helium fusion, which produces carbon and oxygen, and accounts for less than 10% of the star's total lifetime.

In addition, from carbon-burning onwards, energy loss via neutrino production becomes significant, leading to a higher rate of reaction than would otherwise take place.

When the core's mass exceeds the Chandrasekhar limit of about 1.4 M☉, degeneracy pressure can no longer support it, and catastrophic collapse ensues.

As the core's density increases, it becomes energetically favorable for electrons and protons to merge via inverse beta decay, producing neutrons and elementary particles called neutrinos.

Because neutrinos rarely interact with normal matter, they can escape from the core, carrying away energy and further accelerating the collapse, which proceeds over a timescale of milliseconds.

[12] For Type II supernovae, the collapse is eventually halted by short-range repulsive neutron-neutron interactions, mediated by the strong force, as well as by degeneracy pressure of neutrons, at a density comparable to that of an atomic nucleus.

[16] Through a process that is not clearly understood, about 1%, or 1044 joules (1 foe), of the energy released (in the form of neutrinos) is reabsorbed by the stalled shock, producing the supernova explosion.

[19][failed verification] The per-particle energy involved in a supernova is small enough that the predictions gained from the Standard Model of particle physics are likely to be basically correct.

[20] The other crucial area of investigation is the hydrodynamics of the plasma that makes up the dying star; how it behaves during the core collapse determines when and how the shockwave forms and when and how it stalls and is reenergized.

[26][27][28] When the spectrum of a Type II supernova is examined, it normally displays Balmer absorption lines – reduced flux at the characteristic frequencies where hydrogen atoms absorb energy.

When the luminosity of a Type II supernova is plotted over a period of time, it shows a characteristic rise to a peak brightness followed by a decline.

By contrast, the light curve of a Type II-P supernova has a distinctive flat stretch (called a plateau) during the decline; representing a period where the luminosity decays at a slower rate.

In the intermediate width case, the ejecta from the explosion may be interacting strongly with gas around the star – the circumstellar medium.

[31][32] The estimated circumstellar density required to explain the observational properties is much higher than that expected from the standard stellar evolution theory.

[35] Some supernovae of type IIn show interactions with the circumstellar medium, which leads to an increased temperature of the cirumstellar dust.

However, later on the H emission becomes undetectable, and there is also a second peak in the light curve that has a spectrum which more closely resembles a Type Ib supernova.

The progenitor could have been a massive star that expelled most of its outer layers, or one which lost most of its hydrogen envelope due to interactions with a companion in a binary system, leaving behind the core that consisted almost entirely of helium.