Iraq–United States relations

With the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after World War I, the United States supported Great Britain's administration of Iraq as a mandate, but insisted that it be groomed for independence, rather than remain a colony.

The Kennedy administration's initially "low-key" response to the stand-off was motivated by the desire to project an image of the U.S. as "a progressive anti-colonial power trying to work productively with Arab nationalism" as well as the preference of U.S. officials to defer to the U.K. on issues related to the Persian Gulf.

Bundy also requested Kennedy's permission to "press State" to consider measures to resolve the situation with Iraq, adding that cooperation with the British was desirable "if possible, but our own interests, oil and other, are very directly involved.

[40][41][42] On the other hand, Brandon Wolfe-Hunnicutt cites "compelling evidence of an American role,"[38] and that publicly declassified documents "largely substantiate the plausibility" of CIA involvement in the coup.

The most powerful leader of the new government was the secretary of the Iraqi Ba'ath Party, Ali Salih al-Sa'di, who controlled the militant National Guard and organized a massacre of hundreds—if not thousands—of suspected communists and other dissidents in the days following the coup.

"[53] Because, in the words of State Department official James Spain, the "policy of the nationalist Arabs who dominate the Baghdad government does in fact come close to genocide"—as well as a desire to eliminate the Soviets' "Kurdish Card"—the new U.S. ambassador to Iraq, Robert C. Strong, informed al-Bakr of a Barzani peace proposal delivered to the U.S. consul in Tabriz (and offered to convey a response) on August 25.

[55] The Ba'athist government collapsed in November 1963 over the question of unification with Syria (where a different branch of the Ba'ath Party had seized power in March) and the extremist and uncontrollable behavior of al-Sa'di's National Guard.

[58][59] The Lyndon B. Johnson administration favorably perceived Arif's proposal to partially reverse Qasim's nationalization of the IPC's concessionary holding in July 1965 (although the resignation of six cabinet members and widespread disapproval among the Iraqi public forced him to abandon this plan), as well as pro-Western lawyer Abdul Rahman al-Bazzaz's tenure as Prime Minister; Bazzaz attempted to implement a peace agreement with the Kurds following a decisive Kurdish victory at the Battle of Mount Handren in May 1966.

"[63] According to Johnson's National Security Adviser, Walt Whitman Rostow, the NSC even contemplated welcoming Arif on a state visit to the U.S., although this proposal was ultimately rejected due to concerns about the stability of his government.

[70] In May 1968, the CIA produced a report titled "The Stagnant Revolution," stating that radicals in the Iraqi military posed a threat to the Arif government, and while "the balance of forces is such that no group feels power enough to take decisive steps," the ensuing gridlock had created "a situation in which many important political and economic matters are simply ignored.

[73][74] On August 2, Iraqi Foreign Minister Abdul Karim Sheikhli announced that Iraq would seek close ties "with the socialist camp, particularly the Soviet Union and the Chinese People's Republic."

As the Arif government had recently signed a major oil deal with the Soviets, the Ba'ath Party's rapid attempts to improve relations with Moscow were not a complete shock to U.S. policymakers, but they "provided a glimpse at a strategic alliance that would soon emerge.

[79] From the beginning, Johnson administration officials were concerned about "how radical" the Ba'athist government would be—with John W. Foster of the NSC predicting immediately after the coup that "the new group ... will be more difficult than their predecessors"—and, although initial U.S. fears that the coup had been supported by the "extremist" sect of the Ba'ath Party that seized control of Syria in 1966 quickly proved unfounded, by the time President Johnson left office there was a growing belief "that the Ba'ath Party was becoming a vehicle for Soviet encroachment on Iraq's sovereignty.

"[80][81][82] The Richard Nixon administration was confronted with an early foreign policy crisis when Iraq publicly executed 9 Iraqi Jews on fabricated espionage charges at the end of January 1969.

[98][99] On April 9, 1972, Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin signed "a 15-year treaty of friendship and cooperation" with al-Bakr, but U.S. officials were not "outwardly perturbed" by this development, because, according to the NSC staff, it was not "surprising or sudden but rather a culmination of existing relationships.

"[100][101] It has been suggested that Nixon was initially preoccupied with pursuing his policy of détente with the Soviet Union and with the May 1972 Moscow Summit, but later sought to assuage the Shah's concerns about Iraq during his May 30–31 trip to Tehran.

In a May 31 meeting with the Shah, Nixon vowed that the U.S. "would not let down [its] friends," promising to provide Iran with sophisticated weapons ("including F-14s and F-15s") to counter the Soviet Union's agreement to sell Iraq Mig-23 jets.

"[112][113] After a failed coup attempt on June 30, 1973, Saddam consolidated control over Iraq and made a number of positive gestures towards the U.S. and the West, such as refusing to participate in the Saudi-led oil embargo following the Yom Kippur War, but these actions were largely ignored in Washington.

[116] Although the CIA had stockpiled "900,000 pounds of non-attributable small arms and ammunition" to prepare for this contingency, the Kurds were in a weak position due to their lack of anti-aircraft and anti-tank weapons.

Moreover, Soviet advisers contributed to a change in Iraq's tactics that decisively altered the trajectory of the war, allowing the Iraqi army to finally achieve steady gains against the Kurds where it had failed in the past.

[121] A leaked Congressional investigation led by Otis Pike and a February 4, 1976 New York Times article written by William Safire[122] have heavily influenced subsequent scholarship regarding the conduct of the Kurdish intervention.

[131] According to Bryan R. Gibson, "The Pike Report ignored inconvenient truths; misattributed quotes; falsely accused the United States of not providing the Kurds with any humanitarian assistance; and, finally, claimed that Kissinger had not responded to Barzani's tragic plea, when in fact he had ...

A review of thousands of declassified government documents and interviews with former U.S. policymakers shows that the U.S. provided intelligence and logistical support, which played a role in arming Iraq during the Iran–Iraq War.

A report of the U.S. Senate's Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs concluded that the U.S. under the successive presidential administrations sold materials including anthrax, and botulism to Iraq right up until March 1992.

The U.S. provided critical battle planning assistance at a time when U.S. intelligence agencies knew that Iraqi commanders would employ chemical weapons in waging the war, according to senior military officers with direct knowledge of the program.

More significant, in 1983 the Baathist government hosted a United States special Middle East envoy, the highest-ranking American official to visit Baghdad in more than sixteen years.

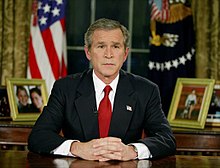

[151] Throughout late 2001, 2002, and early 2003, the Bush Administration worked to build a case for invading Iraq, culminating in then Secretary of State Colin Powell's February 2003 address to the Security Council.

After sharp criticism and public protests as well as lawsuits against the executive order, Trump relaxed the travel restrictions and dropped Iraq from the list of non-entry countries in March 2017.

[163] After a 2020 attack near Baghdad International airport, outgoing Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi condemned America's assassination and stated that the strike was an act of aggression and a breach of Iraqi sovereignty which would lead to war in Iraq.

[169] U.S. officials announced an agreement with the Iraqi government to conclude the military mission against the Islamic State group by 2025, which will involve U.S. troops leaving several bases that they have occupied for nearly two decades.