United States Office of War Information

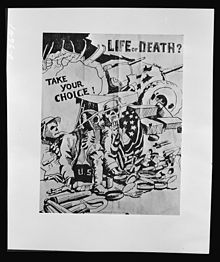

Through radio broadcasts, newspapers, posters, photographs, films and other forms of media, the OWI was the connection between the battlefront and civilian communities.

From 1942 to 1945, the OWI reviewed film scripts, flagging material which portrayed the United States in a negative light, including anti-war sentiment.

But in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the need for coordinated and properly disseminated wartime information from the military/administration to the public outweighed the fears associated with American propaganda.

President Roosevelt entrusted the OWI to journalist and CBS newsman Elmer Davis, with the mission to take "an active part in winning the war and in laying the foundations for a better postwar world".

In conjunction with the War Relocation Authority, the OWI produced a series of documentary films related to the internment of Japanese Americans.

Japanese Relocation and several other films were designed by Milton S. Eisenhower to educate the general public on the internment, to counter the tide of anti-Japanese sentiment in the country, and to encourage Japanese-American internees to resettle outside camp or to enter military service.

The OWI Bureau of Motion Pictures (BMP) headed by Lowell Mellet worked with the Hollywood movie studios to produce films that advanced American war aims.

"[11] Successful films depicted the Allied armed forces as valiant "Freedom fighters", and advocated for civilian participation, such as conserving fuel or donating food to troops.

[17] The Why We Fight series directed by Frank Capra was shown to American soldiers to explain and justify America's involvement in the war.

[19] Abroad, the OWI operated a Psychological Warfare Branch (PWB), which used propaganda to terrorize enemy forces in combat zones, in addition to informing civilian populations in Allied camps.

[20] Leaflet warfare gained popularity during World War II and was utilized in regions such as Northern Africa, Italy, Germany, the Philippines, and Japan.

[22] Millions of leaflets dropped in Sicily read: "The time has come for you to decide whether Italians shall die for Mussolini and Hitler – or live for Italy and civilization".

Known as Operation Annie, the United States 12th Army Group ran a secret radio station from 2:00–6:30 am every morning from a house in Luxembourg pretending to be loyal Rhinelanders under Nazi occupation.

The OWI struggled to present the news (including the pronunciation of town names or and discussion of county or national boundaries) without offending either party.

They operated a sophisticated propaganda machine that sought to demoralize the Japanese army and create a portrait of US war aims that would appeal to the Chinese audience.

[33] From 1942 to 1945, the OWI's Bureau of Motion Pictures reviewed 1,652 film scripts and revised or discarded any that portrayed the United States in a negative light, including material that made Americans seem "oblivious to the war or anti-war."

Elmer Davis, the head of the OWI, said that "The easiest way to inject a propaganda idea into most people's minds is to let it go through the medium of an entertainment picture when they do not realize they're being propagandized".

[35] Further, OWI employees grew ever more dissatisfied with "what they regarded as a turn away from the fundamental, complex issues of the war in favor of manipulation and stylized exhortation".

Some of the writers, producers, and actors of OWI programs admired the Soviet Union and were either loosely affiliated with or were members of the Communist Party USA.

[42][43][44] In his final report, Elmer Davis noted that he had fired 35 employees, because of past Communist associations, though the FBI files showed no formal allegiance to the CPUSA.

After the war, as a broadcast journalist, Davis staunchly defended Owen Lattimore and others from what he considered outrageous and false accusations of disloyalty from Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, Whittaker Chambers and others.

Among the many people who worked for the OWI were Eitaro Ishigaki, Ayako Tanaka Ishigaki, Jay Bennett, Humphrey Cobb, Alan Cranston, Elmer Davis, Gardner Cowles Jr., Martin Ebon, Milton S. Eisenhower, Ernestine Evans, John Fairbank, Lee Falk, Howard Fast, Ralph J. Gleason, Alexander Hammid, Leo Hershfield, Jane Jacobs, Lewis Wade Jones, David Karr, Philip Keeney, Christina Krotkova, Owen Lattimore, Murray Leinster, Paul Linebarger, Irving Lerner, Edward P. Lilly (historian), Alan Lomax, Carol Lunetta Cianca, Archibald MacLeish, Reuben H. Markham, Lowell Mellett, Edgar Ansel Mowrer, Charles Olson, Gordon Parks, James Reston, Peter C. Rhodes, Robert Riskin, Arthur Rothstein, Waldo Salt, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Wilbur Schramm, Robert Sherwood, Dody Weston Thompson (researcher-writer), William Stephenson, George E. Taylor, Chester S. Williams, Flora Wovschin, and Karl Yoneda.